- 2026

- minus20degree, Flachau /P

- 2025

- Transformator, Gedächtnis- & Transformationsraum | spominski & transformacijski prostor, Bad Eisenkappel | Železna Kapla /P

Drugi spomenik / The Other Monument, museum.kärnten, Klagenfurt /V

Paul Albert Leitner`s Photographic World, Camera Austria, Graz /D

2 Tonnen Kalkstein, Kunstraum Ideal, Leipzig (cat.) /G

Nach Anna Lülja Praun, S.I.X., Seewalchen /G

Hinschaun! / Poglejmo!, Kärnten Museum, Klagenfurt /G

Das menschliche und das tierische Wesen, Ursulinenkirche, Linz /E

Suburbia, Architekturzentrum Wien /D

Kardinal König Kunstpreis, Bildraum, Bregenz /G - 2024

- Ich muss mich erstmals sammeln!, HLMD - Hessisches

Landesmuseum Darmstadt /G

Kardinal König Kunstpreis, Lentos, Linz /G

Preise und Talente 2023, Kunstsammlung Oberösterreich, Linz /G

Kulturpreise des Landes Niederösterreich 2024, DOK NÖ Niederösterreichisches Dokumentationszentrum, St.Pölten /G

Neues aus der Sammlung, Kunstsammlung Oberösterreich, Linz /G

Steirische Fotobiennale, Altes Kino Leibnitz /G

Landschaft re_artikulieren, Museum Moderner Kunst Klagenfurt (cat.) /G

Schriftmuseum Pettenbach, Pettenbach /D

Über die Schwelle, Kunst und Kultur der Diözese Linz,

Hallstatt - Kulturhauptstadt Bad Ischl Salzkammergut /G

NHM Biennale Klimatalk#1, Naturhistorisches Museum Wien,

Klima Biennale Vienna /V

Art&Function_Performance, Kunsthaus Mürz, Mürzzuschlag /G

Die Reise der Bilder, Lentos Linz – Kulturhauptstadt Bad Ischl

Salzkammergut (cat.) /G

Broncia Koller-Pinell, Belvedere, Vienna (cat.) /D

Gedenkort Reichenau Innsbruck, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

(competition) /P

Täterätätää, Back with a Bang!, Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Vienna /G

Sudhaus. Kunst mit Salz und Wasser, Kulturhauptstadt Bad Ischl Salzkammergut /G - 2023

- Observations, Collecting Norden, Worlding Northern Art (WONA) and Exploration, Exploitation and Exposition of the Gendered Heritage of the Arctic (XARC), Acadamy of Arts, Tromsø /V

Kyiv Biennale 2023, Vienna /G

Coincidence of Wants, Musa Wien Museum /G

graben/Landschaft/lesen-kopati/Grapo/brati,Bad Eisenkappel/Železna Kapla/G

Wer gedenkt der Partisaninnen und Partisanen? – Kdo se spominja partizank in partizanov?, Museum am Peršmanhof/Muzej Peršmanu, Železna Kapla /G

Labor und Bürogebäude an der Johannes Gutenberg Universität Mainz, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum (Wettbewerb) /P

Display und Ausstellungsraum, BIG ART, BIG, Vienna /D

LBS Holztechnikum Kuchl, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum (competition) /P

Künstler*innenbücher zu Gast: Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch,

Fotohof, Salzburg /E

Shared Space, Versuchsanstalt WUK Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Vienna /E

Edition Camera Austria (Hrsg. Reinhard Braun), Graz /D

@domplatz, Koroška/Kärnten gemeinsam Erinnern / skupno ohranimo spomin, Initiative Domplatz, Universität Klagenfurt /G - 2022

- Das Fest, MAK – Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna /G

Nach 2022 Jahren, Schlossmuseum, Linz /E

Koroška/Kärnten gemeinsam Erinnern / skupno ohranimo spomin, Initiative Domplatz, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum /P

Der Park, St.Agnes, Völkermarkt /G

Lueger Temporär, KÖR, Vienna /E

Inner Boarder, Pavelhaus | Pavlova Hiša, Radkersburg /G

Herbert Bayer, Lentos, Linz /D

Tableaux Vivants/Moving Stills, Architekturforum Zürich /G

Monumental Cares, University of Applied Arts, Vienna /V

XX Y X, Echoraum, Vienna /G

Rethinking Nature, Foto Wien /G - 2021

- Hungry for Time, Academy of Fine Arts Vienna /G

Retrospective Österreichischer Grafikwettbewerb, Taxispalais

Kunsthalle Tirol, Innsbruck /G

Notations, reflections & strategies of display, Contingent Agencies, Vienna /G

Later, gfk-Gesellschaft für Kulturpolitik OÖ, Linz /G

Rethinking Nature, Imago Lisboa, Lisboa /G

Tagung Block Beuys, Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt (cat.) /D

Rethinking Nature, Casino Luxembourg - Forum d'art, Luxembourg /G

A Short History of Camera Traps, Fotograf Gallery, Prague /G

Gemeindezentrum Vöcklamarkt, Art in public space (competition) /P

Forming the Reformed, Academy of Fine Arts, Prague /V - 2020

- Der Angriff der Gegenwart, Universitätsgalerie Heiligenkreuzer Hof, Vienna (cat.) /G

Kärnten Koroška, von A-Ž, Landesgalerie Klagenfurt (cat.) /G

Nach uns die Sintflut, Kunst Haus Vienna (cat.) /G

Die Stadt & Das gute Leben, Camera Austria, Graz /G

Unplugged, Rudolfinum, Prague (cat.) /G

Carinthija, 2020, State Exhibition, Carinthia /G

Sexy Pages, Atelierhaus Hannover /G

Feuerstelle, lower austrian culture, art in public space , Klein-Meiseldorf /P

Fastentuch Vöcklamarkt, Diözesankonservatorat Linz /P

Die Nachbarn, Art in public space, Salzburg (competition) /P

Editionale Wien, University of Applied Arts, Vienna /G

The World to Come, DePaul Art Museum, Chicago (cat.) /G - 2019

- Ozeanische Gefühle, Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt /E

Im Raum die Zeit lesen, mumok - Museum moderner Kunst

Stiftung Ludwig, Vienna /G

Vienna Art Book Fair #1, VABF with University of Applied Arts Vienna /G

Tag des Denkmals - Sea of Tranquility, The Pit, Breitenbrunn /V

Cinema of the Anthropocene, UNC-Wilmington, North Carolina /V

50 Jahre Mondlandung-10 Jahre Salzamt, Salzamt, Linz /G

ticket to the moon, Kunsthalle Krems (cat.) /G

Für die Vögel, lower austrian culture, art in public space /P

The World to Come, UMMA University Michigan Museum of Art (cat.) /G

Lentos-Außen, Linz (competition) /P

Klagenfurter Kunstfilmtage, Klagenfurt /V

Österreichbild, Architekturzentrum Vienna /P

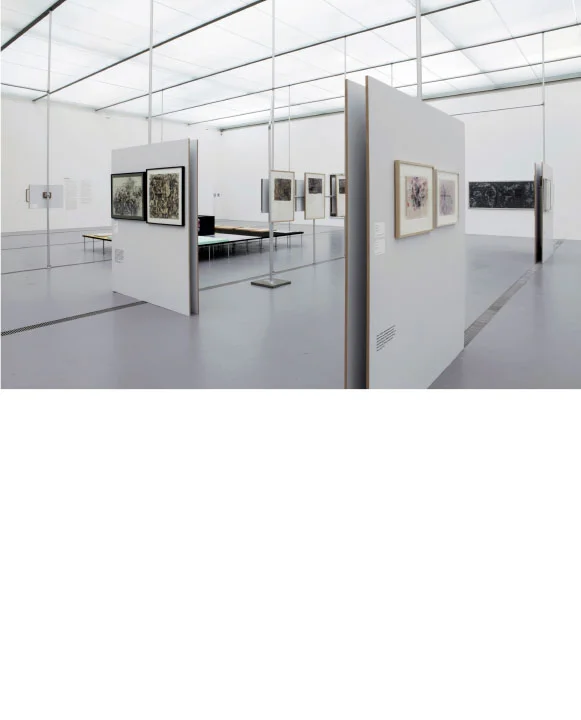

Lassnig-Rainer, Lentos, Linz (cat.) /D - 2018

- Aufbruch ins Ungewisse – Österreich seit 1918,

Haus der Geschichte, Vienna /G

Lost and Found, T.R.A.M., Vienna/Bratislava (cat.) /P

In the case, haaaauch-quer, Klagenfurt /P

Das Denkmal, Museum und Gedenkstätte Peršmanhof, Železna Kapla /V

Rennes Ours, colophon, achevé d'imprimer : le livre d'artiste et le péritexte, Cabinet du Livre d'artiste, Agen, France /G

Project for the preservation of a tumulus, Großmugl, Lower Austria /P

Sommerfrische Reloaded 2018, S.I.X., Seewalchen /G

The World to Come, Harn Museum of Art, Florida (cat.) /G

Yesterday Today Today, Kunstraum Buchberg, Schloss Buchberg (cat.) /G

Garten der Künstler, Minoritenkloster, Tulln (cat.) /G

Post Otto Wagner, MAK – Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna (cat.) /G

Das andere Land, Museum Moderner Kunst Klagenfurt (cat.) /G

1918- Klimt. Moser. Schiele. Gesammelte Schönheiten, Lentos, Linz /D

Auf die Plätze / Na mesta, Künstlerhaus Klagenfurt /G - 2017

- Floor, Wall, Body, Offspace-Night Vienna Art Week, Vienna /V

Grau in Grau – Ästhetisch Politische Praktiken der Erinnerungskultur,

Kunstuniversität Linz /V

Flüchtige Territorien, Kunstraum Niederösterreich, Vienna (cat.) /G

Uncommon Places, Goethe Institut, Hongkong /G

Mapping Terrains, Arccart, Vienna /G

Stretching the Boundaries, Fluca, Plovdiv /G

Kunst am Bau, Bruckner-Universität, Linz (competition) /P

Sterne. Kosmische Kunst, Lentos, Linz (cat.) /G

Un-Curating the Archive, Camera Austria, Graz /E

Unschärfen und weiße Flecken, Künsthaus Mürz (cat.) /G

AHEAD of the Game!, Künstlerhaus Klagenfurt /G - 2016

- Einrichtung, Camera Austria, Graz /D

Psst: there is still place in outer space!, Pavelhaus/Pavlova Hiša,

Radkersburg /G

Am Ende: Architektur, Architekturzentrum Vienna /D

Mahnmal für aktive Gewaltfreiheit, Linz (competition) /P

Herwig Turk Landschaft=Labor, Museum Moderner Kunst

Klagenfurt (cat.) /G

Ein stiller Begleiter, Großmugl /P

Seeing is believing, Museum Angerlehner, Wels (cat.) /G

SUPER J’arrive, Super Wien, Vienna /G - 2015

- Das Denkmal, Institut für Staatswissenschaften, Vienna /V

Filmbau. Schweizer Architektur im bewegten Bild, SAM Schweizerisches

Architekturmuseum, Basel (cat.) /G

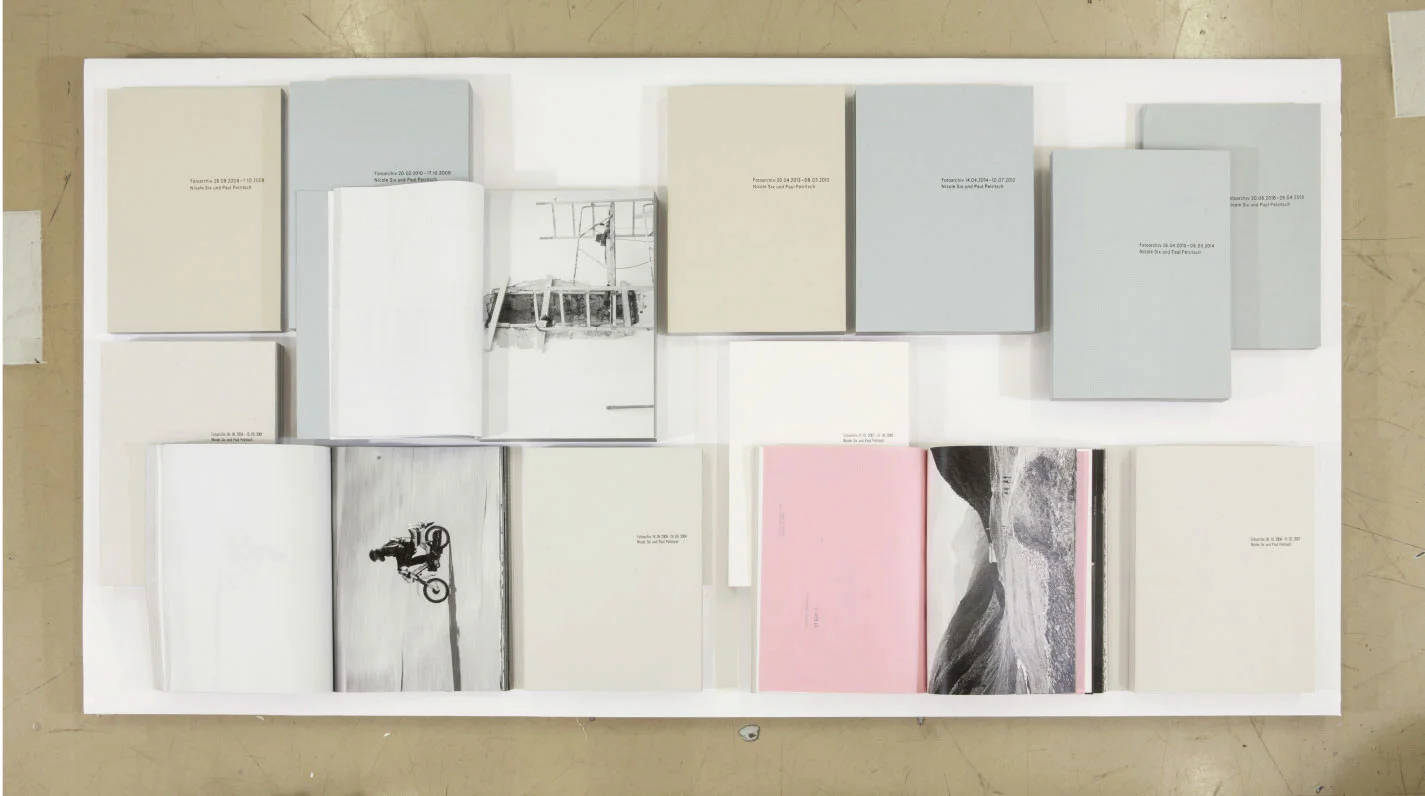

Mehr als Zero, Hans Bischoffshausen, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere,

Vienna (cat.) /D

Fronteras En Cuestión II, Centro de Desarollo de las Artes Visuales,

Habana /G

Revers de Tromp, Academy of fine arts Vienna /G

Das Denkmal, Parallel Vienna, Vienna /G

Palm Capsule, Exposition Park, Los Angeles /P

Uncommon Places, Synthesis Gallery of Photography, Sofia /G

Fictitious Tales about the History of Earth, MAK Center, Los Angeles /G

Nicole Six & Paul Petritsch, Das Denkmal, Kunstraum Lakeside,

Klagenfurt /E

Mainzer Ansichten, Kunsthalle Mainz /E

The Visual Paradigm, Camera Austria, Graz /G

Vienna for Art`s Sake, Winter-Palast Belvedere, Vienna (cat.) /G - 2014

- Lichtblicke, Universitätskulturzentrum UNIKUM und section a, Trzic /G

Korrelation, Angewandte Innovation Laboratory, Vienna /G

Wirklichkeit und Konstruktion, Stadtgalerie Klagenfurt (cat.) /G

Die Gegenwart der Moderne, Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig /V

Unframed, Galerie Raum mit Licht und Eikon, Vienna /G

Archives, Re-Assemblances and Surveys, On Austrian Contemporary

Photography, Klovicevi dvori Gallery, Zagreb (cat.) /G

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch, Das Meer der Stille, Landesgalerie Linz (cat.) /E

Fade into You, Kunsthalle Mainz /V

MAK Design Labor, MAK – Österreichisches Museum für angewandte

Kunst, Vienna /G

Places of Transition, Freiraum – MuseumsQuartier Wien (cat.) /D - 2013

- Suicide Narcissus, The Renaissance Society, Chicago /G

Gefährdung, Entzug und grundloses Aushalten, Transmediale Kunst -

Universität für angewandte Kunst, Vienna /V

Vienna for Art`s Sake, Benetton Collection, Treviso (cat.) /G

Kunstgastgeber – Rennbahnweg 27, KÖR Kunst im öffentlichen Raum,

Vienna (Kat.) /P

Denkmal für die Verfolgten der NS-Miltärjustiz, Ballhausplatz 1010 Vienna /P

Nebelland hab ich gesehen, Museum Moderner Kunst Klagenfurt (cat.) /G

Is it really you, Kunstsammlung Oberösterreich, Linz /G

Praxis der Liebe, Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg /D

Das Bauhaus in Kalkutta, Bauhaus Dessau /D

Wolken, Welt des Flüchtigen, Leopold Museum, Vienna (cat.) /G

Schuss / Gegenschuss, in: Camera Austria, Nr. 121 /P - 2012

- Art is Concrete, Camera Austria, Graz /D

Sowjetmoderne, Architekturzentrum Vienna /D

Aus, Schluss Basta oder Wir sind total am Ende, Schauspielhaus Graz /V

Keine Zeit, erschöpftes Selbst / entgrenzetes Können, 21er Haus,

Vienna (cat.) /G

Space Affairs, Musa, Vienna /G

Aussicht kann durch Ladung verstellt sein, Kunstverein Medienturm,

Graz (cat.) /E - 2011

- Im täglichen Wahnsinn den Zauber finden!, Kunstraum Goethestrasse

xtd, Linz /G

Schall und Rauch, die Vertikale und der freie Fall, TransArts - Universität

für angewandte Kunst, Vienna /V

If a tree falls in the forest, and nobody hears it, does it make a sound?,

Galerie Lisa Ruyter, Vienna /G

Das Ding an sich, Mariendom, Linz /P

Raum für 17 Minuten 6’23’’, Galerie im Taxispalais, Innsbruck (cat.) /E

Prima Interventionen, Atelierhaus Salzamt, Linz /G

Proposals for Venice, Landesgalerie Linz (cat.) /G - 2010

- Körper Codes, Museum der Moderne Salzburg /G

Der Aufstand der Zeichen, k48, Vienna, Intervention im öffentlichen Raum /P

Heimat/Domovina, Museum Moderner Kunst Klagenfurt (cat.) /G

Triennale Linz 1.0, Linz (cat.) /G

Blind Date, Kunstverein Hannover /E

Atlas, Secession, Vienna (cat.) /E

Upon Arrival, Malta Contemporary Art, Malta (cat.) /G - 2009

- Österreichischer Grafikwettbewerb (31), Galerie im Taxispalais,

Innsbruck (cat.) /G

Mahnmal für die Zwangsarbeitslager St. Pölten - Viehofen,

in Zusammenarbeit mit Jeanette Pacher (nicht realisiert) /P

Das menschliche und das tierische Wesen, Ursulinenkirche, Linz /E

Reading the City, ev+a 2009, Limerick (cat.) /G

Spotlight, Museum der Moderne, Salzburg /G - 2008

- Undiszipliniert, Das Phänomen Raum in Kunst, Architektur und Design, Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Vienna (cat.) /G

Peter Zumthor, Bauten und Projekte 1986–2007 mit einer Filminstallation von Nicole Six & Paul Petritsch, Experimentadesign, Lissabon /P

zu Gironcoli, Gironcoli Museum, Herberstein /G

K08, Emanzipation und Konfrontation, Künstlerhaus Klagenfurt (cat.) /G

Was ist ein Platz? Was ist ein Cy-BORG-Platz?, Temporäre Kunst im Stadtraum, Wiener Neustadt /P

unterwegs sein, Kunstraum Düsseldorf (cat.) /G

Bildpolitiken, Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg /D

Kontakt...aus der Sammlung der Erste Bank-Gruppe, Institut

of Contemporary Art, Dunaújváros /D

zoom and scale, Akademie der bildenden Künste, Vienna /G - 2007

- Max Ernst und die Welt im Buch, Museum der Moderne, Salzburg /G

Peter Zumthor, Bauten und Projekte 1986–2007 mit einer Filminstallation von Nicole Six & Paul Petritsch, KUB Kunsthaus Bregenz /P

Temporally, The Israeli Center for Digital Art, Holon /G

Margherita Spiluttini. Atlas Austria, Architekturzentrum Vienna /D

Kunstverein Baden, Kunstverein Baden /G

Blickwechsel Nr.3, MMKK, Klagenfurt (cat.) /G

I`m too tired to tell you, Agentur, Amsterdam /E

Film ab, Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst, BIG, Vienna /P

Kontakt Belgrad...aus der Sammlung der Erste Bank-Gruppe, Museum Moderner Kunst, Belgrad /D - 2006

- Longitude / Latitude, haaaauch, Klagenfurt /E

Nicole Six / Paul Petritsch, Gesellschaft für aktuelle Kunst, Bremen /E

First the artist defines meaning, Camera Austria, Graz /G

Société des nations, Circuit, Lausanne /G

How and Wow, Experimentelle Gestaltung Kunstuniversität Linz, Linz /V

Kontakt...aus der Sammlung der Erste Bank-Gruppe, Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig, Vienna /D

Margherita Spiluttini. Atlas Austria, Architekturzentrum Wien mit Arco, Madrid /D - 2005

- Tu Felix Austria…Wild at Heart, KUB Kunsthaus Bregenz (cat.) /G

Home Stories, Architekturzentrum Wien mit Austrian Cultural Forum,

New York /D

Das Spannende ist doch die Organisation von Materie, Area 53, Vienna /G

Wisdom of Nature, Nagoya City Art Museum, Nagoya (cat.) /G

Das Neue 2, Atelier im Augarten, Zentrum für zeitgenössische Kunst der Österreichischen Galerie Belvedere, Vienna (cat.) /G

Großmugl, Wettbewerb Kunst im öffentlichen Raum, Großmugl

(unrealized) /P

Museums-Empfangsbereich, Frac Lorraine, Metz, Frankreich /P

Slices of Life, blueprints of the self in painting, Austrian Cultural Forum,

New York /D - 2004

- Open Studio, ISCP, New York /G

Transgressing-Systems, Ausstellen zu Bauen und Kunst, Innsbruck /G

1.33.33, Area 53, Wien /G

Permanent Produktiv, Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Vienna /G

White Spirit in Public Spaces, F.R.A.C. de Lorrain, Metz /G

The Austrian Phenomenon / Konzepte Experimente Wien Graz 1958-1973, Architekturzentrum Vienna /D - 2003

- Fata Morgana, Wettbewerb Silos Graz-West, Kulturhauptstadt Graz 2003

in collaboration with Jeanette Pacher (unrealized) /P

Flutlichtmast, Wettbewerb Kunst im öffentlichen Raum in Rohrendorf

in collaboration with Hans Schabus (unrealized) /P

Trauer, Atelier im Augarten, Zentrum für zeitgenössische Kunst der Österreichischen Galerie Belvedere, Vienna (cat.) /G

America, bgf_plattform, Berlin /G

Extended Architecture, Tanzwerkstatt Europa, Neues Theater, München /G

just build it! Die Bauten des Rural Studio, Architekturzentrum Vienna /D

site-seeing: disneyfizierung der städte, Künstlerhaus Vienna /D - 2002

- artists´choice, CAT Contemporary Art Tower – MAK

Gegenwartskunstdepot, Vienna /E

space off, supersaat, Vienna /G - 2001

- moving out, Universität für angewandte Kunst, Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Vienna /D

/E Solo Exhibition

/G Group Exhibition

/P Projects: Interventions, Public Space, Competition or realized Projects

/D Display: Exhibition, Catalogs

/V Lecture and Screenings, Presentations

- 2026

- minus20degree, Flachau /P

- 2025

- Transformator, Gedächtnis- & Transformationsraum | spominski & transformacijski prostor, Bad Eisenkappel | Železna Kapla /P

Drugi spomenik / Das andere Denkmal, museum.kärnten, Klagenfurt /V

Paul Albert Leitner`s Photographic World, Camera Austria, Graz /D

2 Tonnen Kalkstein, Kunstraum Ideal, Leipzig (Katalog) /G

Nach Anna Lülja Praun, S.I.X., Seewalchen /G

Hinschaun! / Poglejmo!, Kärnten Museum, Klagenfurt /G

Das menschliche und das tierische Wesen, Ursulinenkirche, Linz /E

Suburbia, Architekturzentrum Wien /D

Kardinal König Kunstpreis, Bildraum, Bregenz /G - 2024

- Ich muss mich erstmals sammeln!, HLMD - Hessisches

Landesmuseum Darmstadt /G

Kardinal König Kunstpreis, Lentos, Linz /G

Preise und Talente 2023, Kunstsammlung Oberösterreich, Linz /G

Kulturpreise des Landes Niederösterreich 2024, DOK NÖ Niederösterreichisches Dokumentationszentrum, St.Pölten /G

Neues aus der Sammlung, Kunstsammlung Oberösterreich, Linz /G

Steirische Fotobiennale, Altes Kino Leibnitz /G

Landschaft re_artikulieren, Museum Moderner Kunst Klagenfurt (Katalog) /G

Schriftmuseum Pettenbach, Pettenbach /D

Über die Schwelle, Kunst und Kultur der Diözese Linz,

Hallstatt - Kulturhauptstadt Bad Ischl Salzkammergut /G

NHM Biennale Klimatalk#1, Naturhistorisches Museum Wien,

Klima Biennale Wien /V

Art&Function_Performance, Kunsthaus Mürz, Mürzzuschlag /G

Die Reise der Bilder, Lentos – Kulturhauptstadt Bad Ischl

Salzkammergut (Katalog) /G

Broncia Koller-Pinell, Belvedere, Wien (Katalog) /D

Gedenkort Reichenau Innsbruck, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

(Wettbewerb) /P

Täterätätää, Back with a Bang!, Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Wien /G

Sudhaus. Kunst mit Salz und Wasser, Kulturhauptstadt Bad Ischl Salzkammergut /G - 2023

- Observations, Collecting Norden, Worlding Northern Art (WONA) and Exploration, Exploitation and Exposition of the Gendered Heritage of the Arctic (XARC), Acadamy of Arts, Tromsø /V

Kyiv Biennale 2023, Wien /G

Coincidence of Wants, Musa Wien Museum /G

graben/Landschaft/lesen-kopati/Grapo/brati,Bad Eisenkappel/Železna Kapla/G

Wer gedenkt der Partisaninnen und Partisanen? – Kdo se spominja partizank in partizanov?, Museum am Peršmanhof/Muzej Peršmanu, Železna Kapla /G

Labor und Bürogebäude an der Johannes Gutenberg Universität Mainz, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum (Wettbewerb) /P

Display und Ausstellungsraum, BIG ART, BIG, Wien /D

LBS Holztechnikum Kuchl, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum (Wettbewerb) /P

Künstler*innenbücher zu Gast: Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch,

Fotohof, Salzburg /E

Shared Space, Versuchsanstalt WUK Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Wien /E

Edition Camera Austria (Hrsg. Reinhard Braun), Graz /D

@domplatz, Koroška/Kärnten gemeinsam Erinnern / skupno ohranimo spomin, Initiative Domplatz, Universität Klagenfurt /G - 2022

- Das Fest, MAK – Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Wien /G

Nach 2022 Jahren, Schlossmuseum, Linz /E

Koroška/Kärnten gemeinsam Erinnern / skupno ohranimo spomin, Initiative Domplatz, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum /P

Der Park, St.Agnes, Völkermarkt /G

Lueger Temporär, KÖR, Wien /E

Inner Boarder, Pavelhaus | Pavlova Hiša, Radkersburg /G

Herbert Bayer, Lentos, Linz /D

Tableaux Vivants/Moving Stills, Architekturforum Zürich /G

Monumental Cares, Universität für angewandte Kunst, Wien /V

XX Y X, Echoraum, Wien /G

Rethinking Nature, Foto Wien /G - 2021

- Hungry for Time, Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien /G

Retrospective Österreichischer Grafikwettbewerb, Taxispalais

Kunsthalle Tirol, Innsbruck /G

Notations, reflections & strategies of display, Contingent Agencies, Wien /G

Later, gfk-Gesellschaft für Kulturpolitik OÖ, Linz /G

Rethinking Nature, Imago Lisboa, Lissabon /G

Tagung Block Beuys, Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt (Kat.) /D

Rethinking Nature, Casino Luxembourg - Forum d'art, Luxembourg /G

A Short History of Camera Traps, Fotograf Gallery, Prag /G

Gemeindezentrum Vöcklamarkt, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

(Wettbewerb) /P

Forming the Reformed, Akademie der Bildenden Künste Prag /V - 2020

- Der Angriff der Gegenwart, Universitätsgalerie Heiligenkreuzer Hof, Wien (Kat.) /G

Kärnten Koroška, von A-Ž, Landesgalerie Klagenfurt (Kat.) /G

Nach uns die Sintflut, Kunst Haus Wien (Kat.) /G

Die Stadt & Das gute Leben, Camera Austria, Graz /G

Unplugged, Rudolfinum, Prag (Kat.) /G

Carinthija, 2020, Landesausstellung, Kärnten /G

Sexy Pages, Atelierhaus Hannover /G

Feuerstelle, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum Niederösterreich, Klein-Meiseldorf /P

Fastentuch Vöcklamarkt, Diözesankonservatorat Linz /P

Die Nachbarn, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum Salzburg (Wettbewerb) /P

Editionale Wien, Universität für angewandte Kunst, Wien /G

The World to Come, DePaul Art Museum, Chicago (Kat.) /G - 2019

- Ozeanische Gefühle, Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt /E

Im Raum die Zeit lesen, Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig, Wien /G

Vienna Art Book Fair #1, VABF+Universität für angewandte Kunst Wien /G

Tag des Denkmals - Sea of Tranquility, The Pit, Breitenbrunn /V

Cinema of the Anthropocene, UNC-Wilmington, North Carolina /V

50 Jahre Mondlandung-10 Jahre Salzamt, Salzamt, Linz /G

ticket to the moon, Kunsthalle Krems (Kat.) /G

Für die Vögel, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum Niederösterreich /P

The World to Come, UMMA University Michigan Museum of Art (Kat.) /G

Lentos-Außen, Linz (Wettbewerb) /P

Klagenfurter Kunstfilmtage, Klagenfurt /V

Österreichbild, Architekturzentrum Wien /P

Lassnig-Rainer, Lentos, Linz (Kat.) /D - 2018

- Aufbruch ins Ungewisse – Österreich seit 1918,

Haus der Geschichte, Wien /G

Lost and Found, T.R.A.M., Wien/Bratislava (Kat.) /P

In the case, haaaauch-quer, Klagenfurt /P

Das Denkmal, Museum und Gedenkstätte Peršmanhof, Železna Kapla /V

Rennes Ours, colophon, achevé d'imprimer : le livre d'artiste et le péritexte, Cabinet du Livre d'artiste, Agen, Frankreich /G

Projekt zum Schutz eines Hügelgrabs, Großmugl, Niederösterreich /P

Sommerfrische Reloaded 2018, S.I.X., Seewalchen /G

The World to Come, Harn Museum of Art, Florida (Kat.) /G

Yesterday Today Today, Kunstraum Buchberg, Schloss Buchberg (Kat.) /G

Garten der Künstler, Minoritenkloster, Tulln (Kat.) /G

Post Otto Wagner, MAK – Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst, Wien (Kat.) /G

Das andere Land, Museum Moderner Kunst Klagenfurt (Kat.) /G

1918- Klimt. Moser. Schiele. Gesammelte Schönheiten, Lentos, Linz /D

Auf die Plätze / Na mesta, Künstlerhaus Klagenfurt /G - 2017

- Floor, Wall, Body, Offspace-Night Vienna Art Week, Wien /V

Grau in Grau – Ästhetisch Politische Praktiken der Erinnerungskultur,

Kunstuniversität Linz /V

Flüchtige Territorien, Kunstraum Niederösterreich, Wien (Kat.) /G

Uncommon Places, Goethe Institut, Hongkong /G

Mapping Terrains, Arccart, Wien /G

Stretching the Boundaries, Fluca, Plovdiv /G

Kunst am Bau, Bruckner-Universität, Linz (Wettbewerb) /P

Sterne. Kosmische Kunst, Lentos, Linz (Kat.) /G

Un-Curating the Archive, Camera Austria, Graz /E

Unschärfen und weiße Flecken, Künsthaus Mürz (Kat.) /G

AHEAD of the Game!, Künstlerhaus Klagenfurt /G - 2016

- Einrichtung,, Camera Austria, Graz /D

Psst: there is still place in outer space!, Pavelhaus/Pavlova Hiša,

Radkersburg /G

Am Ende: Architektur, Architekturzentrum Wien /D

Mahnmal für aktive Gewaltfreiheit, Linz (Wettbewerb) /P

Herwig Turk Landschaft=Labor, Museum Moderner Kunst

Klagenfurt (Kat.) /G

Ein stiller Begleiter, Großmugl /P

Seeing is believing, Museum Angerlehner, Wels (Kat.) /G

SUPER J’arrive, Super Wien /G - 2015

- Das Denkmal, Institut für Staatswissenschaften, Wien /V

Filmbau. Schweizer Architektur im bewegten Bild, SAM Schweizerisches

Architekturmuseum, Basel (Kat.) /G

Mehr als Zero, Hans Bischoffshausen, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere,

Wien (Kat.) /D

Fronteras En Cuestión II, Centro de Desarollo de las Artes Visuales,

Habana /G

Revers de Tromp, Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien /G

Das Denkmal, Parallel Vienna, Wien /G

Palm Capsule, Exposition Park, Los Angeles /P

Uncommon Places, Synthesis Gallery of Photography, Sofia /G

Fictitious Tales about the History of Earth, MAK Center, Los Angeles /G

Nicole Six & Paul Petritsch, Das Denkmal, Kunstraum Lakeside,

Klagenfurt /E

Mainzer Ansichten, Kunsthalle Mainz /E

The Visual Paradigm, Camera Austria, Graz /G

Vienna for Art`s Sake, Winter-Palast Belvedere, Wien (Kat.) /G - 2014

- Lichtblicke, Universitätskulturzentrum UNIKUM und section a, Trzic /G

Korrelation, Angewandte Innovation Laboratory, Wien /G

Wirklichkeit und Konstruktion, Stadtgalerie Klagenfurt (Kat.) /G

Die Gegenwart der Moderne, Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig /V

Unframed, Galerie Raum mit Licht und Eikon, Wien /G

Archives, Re-Assemblances and Surveys, On Austrian Contemporary

Photography, Klovicevi dvori Gallery, Zagreb (Kat.) /G

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch, Das Meer der Stille, Landesgalerie Linz (Kat.) /E

Fade into You, Kunsthalle Mainz /V

MAK Design Labor, MAK – Österreichisches Museum für angewandte

Kunst, Wien /G

Places of Transition, Freiraum – MuseumsQuartier Wien (Kat.) /D - 2013

- Suicide Narcissus, The Renaissance Society, Chicago /G

Gefährdung, Entzug und grundloses Aushalten, Transmediale Kunst -

Universität für angewandte Kunst, Wien /V

Vienna for Art`s Sake, Benetton Collection, Treviso (Kat.) /G

Kunstgastgeber – Rennbahnweg 27, KÖR Kunst im öffentlichen Raum,

Wien (Kat.) /P

Denkmal für die Verfolgten der NS-Miltärjustiz, Ballhausplatz 1010 Wien /P

Nebelland hab ich gesehen, Museum Moderner Kunst Klagenfurt (Kat.) /G

Is it really you, Kunstsammlung Oberösterreich, Linz /G

Praxis der Liebe, Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg /D

Das Bauhaus in Kalkutta, Bauhaus Dessau /D

Wolken, Welt des Flüchtigen, Leopold Museum, Wien (Kat.) /G

Schuss / Gegenschuss, in: Camera Austria, Nr. 121 /P - 2012

- Art is Concrete, Camera Austria, Graz /D

Sowjetmoderne, Architekturzentrum Wien /D

Aus, Schluss Basta oder Wir sind total am Ende, Schauspielhaus Graz /V

Keine Zeit, erschöpftes Selbst / entgrenzetes Können, 21er Haus,

Wien (Kat.) /G

Space Affairs, Musa, Wien /G

Aussicht kann durch Ladung verstellt sein, Kunstverein Medienturm,

Graz (Kat.) /E - 2011

- Im täglichen Wahnsinn den Zauber finden!, Kunstraum Goethestrasse

xtd, Linz /G

Schall und Rauch, die Vertikale und der freie Fall, TransArts - Universität

für angewandte Kunst, Wien /V

If a tree falls in the forest, and nobody hears it, does it make a sound?,

Galerie Lisa Ruyter, Wien /G

Das Ding an sich, Mariendom, Linz /P

Raum für 17 Minuten 6’23’’, Galerie im Taxispalais, Innsbruck (Kat.) /E

Prima Interventionen, Atelierhaus Salzamt, Linz /G

Proposals for Venice, Landesgalerie Linz (Kat.) /G - 2010

- Körper Codes, Museum der Moderne Salzburg /G

Der Aufstand der Zeichen, k48, Wien, Intervention im öffentlichen Raum /P

Heimat/Domovina, Museum Moderner Kunst Klagenfurt (Kat.) /G

Triennale Linz 1.0, Linz (Kat.) /G

Blind Date, Kunstverein Hannover /E

Atlas, Secession, Wien (Kat.) /E

Upon Arrival, Malta Contemporary Art, Malta (Kat.) /G - 2009

- Österreichischer Grafikwettbewerb (31) , Galerie im Taxispalais,

Innsbruck (Kat.) /G

Mahnmal für die Zwangsarbeitslager St. Pölten - Viehofen,

in Zusammenarbeit mit Jeanette Pacher (nicht realisiert) /P

Das menschliche und das tierische Wesen, Ursulinenkirche, Linz /E

Reading the City, ev+a 2009, Limerick (Kat.) /G

Spotlight, Museum der Moderne, Salzburg /G - 2008

- Undiszipliniert, Das Phänomen Raum in Kunst, Architektur und Design, Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Wien (Kat.) /G

Peter Zumthor, Bauten und Projekte 1986–2007 mit einer Filminstallation von Nicole Six & Paul Petritsch, Experimentadesign, Lissabon /P

zu Gironcoli, Gironcoli Museum, Herberstein /G

K08, Emanzipation und Konfrontation, Künstlerhaus Klagenfurt (Kat.) /G

Was ist ein Platz? Was ist ein Cy-BORG-Platz?, Temporäre Kunst im Stadtraum, Wiener Neustadt /P

unterwegs sein, Kunstraum Düsseldorf (Kat.) /G

Bildpolitiken, Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg /D

Kontakt...aus der Sammlung der Erste Bank-Gruppe, Institut

of Contemporary Art, Dunaújváros (Display) /D

zoom and scale, Akademie der bildenden Künste, Wien /G - 2007

- Max Ernst und die Welt im Buch, Museum der Moderne, Salzburg /G

Peter Zumthor, Bauten und Projekte 1986–2007 mit einer Filminstallation von Nicole Six & Paul Petritsch, KUB Kunsthaus Bregenz /P

Temporally, The Israeli Center for Digital Art, Holon /G

Margherita Spiluttini. Atlas Austria, Architekturzentrum Wien /D

Kunstverein Baden, Kunstverein Baden /G

Blickwechsel Nr.3, MMKK, Klagenfurt (Kat.) /G

I`m too tired to tell you, Agentur, Amsterdam /E

Film ab, Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst, BIG, Wien /P

Kontakt Belgrad...aus der Sammlung der Erste Bank-Gruppe, Museum Moderner Kunst, Belgrad /D - 2006

- Longitude / Latitude, haaaauch, Klagenfurt /E

Nicole Six / Paul Petritsch, Gesellschaft für aktuelle Kunst, Bremen /E

First the artist defines meaning, Camera Austria, Graz /G

Société des nations, Circuit, Lausanne /G

How and Wow, Experimentelle Gestaltung Kunstuniversität Linz, Linz /V

Kontakt...aus der Sammlung der Erste Bank-Gruppe, Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig, Wien /D

Margherita Spiluttini. Atlas Austria, Architekturzentrum Wien mit Arco, Madrid /D - 2005

- Tu Felix Austria…Wild at Heart, KUB Kunsthaus Bregenz (Kat.) /G

Home Stories, Architekturzentrum Wien mit Austrian Cultural Forum,

New York /D

Das Spannende ist doch die Organisation von Materie, Area 53, Wien /G

Wisdom of Nature, Nagoya City Art Museum, Nagoya (Kat.) /G

Das Neue 2, Atelier im Augarten, Zentrum für zeitgenössische Kunst der Österreichischen Galerie Belvedere, Wien (Kat.) /G

Großmugl, Wettbewerb Kunst im öffentlichen Raum, Großmugl

(nicht realisiert) /P

Museums-Empfangsbereich, Frac Lorraine, Metz, Frankreich /P

Slices of Life, blueprints of the self in painting, Austrian Cultural Forum,

New York /D - 2004

- Open Studio, ISCP, New York /G

Transgressing-Systems, Ausstellen zu Bauen und Kunst, Innsbruck /G

1.33.33, Area 53, Wien /G

Permanent Produktiv, Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Wien /G

White Spirit in Public Spaces, F.R.A.C. de Lorrain, Metz /G

The Austrian Phenomenon / Konzepte Experimente Wien Graz 1958-1973, Architekturzentrum Wien /D - 2003

- Fata Morgana, Wettbewerb Silos Graz-West, Kulturhauptstadt Graz 2003

in Zusammenarbeit mit Jeanette Pacher (nicht realisiert) /P

Flutlichtmast, Wettbewerb Kunst im öffentlichen Raum in Rohrendorf

in Zusammenarbeit mit Hans Schabus (nicht realisiert) /P

Trauer, Atelier im Augarten, Zentrum für zeitgenössische Kunst der Österreichischen Galerie Belvedere, Wien (Kat.) /G

America, bgf_plattform, Berlin /G

Extended Architecture, Tanzwerkstatt Europa, Neues Theater, München /G

just build it! Die Bauten des Rural Studio, Architekturzentrum Wien /D

site-seeing: disneyfizierung der städte, Künstlerhaus Wien /D - 2002

- artists´choice, CAT Contemporary Art Tower – MAK

Gegenwartskunstdepot, Wien /E

space off, supersaat, Wien /G - 2001

- moving out, Universität für angewandte Kunst, Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien /D

/E Einzelausstellungen

/G Gruppenausstellungen

/P Projekte: Intervention, öffentlicher Raum, Wettbewerbe oder realisiert Projekte

/D Display: Ausstellungen, Katalog

/V Vorträge u. Screening, Präsentation

FILMS

- 2025

- Drugi spomenik / Das andere Denkmal

Video with sound

one-channel projection

32 min 22 sec, colour - 2024

- Seemeile (Sumbu und Pekel)

Video with sound

one-channel projection

20 min 49 sec, colour

Die Reise der Bilder

Video with sound

eight-channel projection

24 min 24 sec - 33min 23 sec, colour - 2023

- Lueger Temporär

Video with sound

one-channel projection

22 min 11 sec, colour

05.01.2023 (Pečnikov travnik/Pečnik-Wiese)

Video with sound

four-channel projection

1h 50min, colour - 2021

- Pilot

(Dialogisch den Horizont expandieren - von Klagenfurt nach Klagenfurt)

Video with sound

one-channel projection

11 min 08 sec, colour

Roxy, 27.05.2021 (Block Beuys)

Video with sound

one-channel projection

8 min 12 sec, colour - 2020

- Parallel Worlds

20.03.2020 / 01.04.2020 / 20.04.2020

Video with sound

three-channel projection

23 min 12sec, colour - 2017

- Ohne Titel (Albaner Hafen)

Video with sound

three-channel projection

51 min, colour - 2015

- Das Denkmal

Video with sound

two-channel projection

130 min, colour - 2014

- Raum für 5’16’’

Video with sound

two-channel projection

5 min 16 sec, colour

Das Meer der Stille

Video with sound on DVD

3 min 34 sec, colour - 2011

- Raum für 17 Minuten 6’23’’

Video with sound

two-channel projection

6 min 23 sec, colour - 2009

- Das menschliche und das tierische Wesen

Video with sound

five-channel projection

19 min, colour - 2007

- Ohne Titel, twelve buildings by Peter Zumthor

Video with sound

six-channel projection

480 min, colour

Nebel

Video with sound on DVD

30 min, colour - 2005

- Ohne Titel, Kunsthaus Bregenz

Video with sound on DVD

six-channel projection

72 h, colour

I’m too tired to tell you

Video on DVD

17 min, colour, silent - 2004

- Longitude / Latitude

Video on DVD

77 min, colour, silent

Raum

Video with sound on DVD

60 min, colour - 2003

- Camera dead

Video with sound on DVD

35 sec, colour

Räumliche Maßnahme (2)

Video with sound on DVD

two-channel projection

50 min, colour - 2002

- Räumliche Maßnahme (1)

Video with sound on DVD

28 min, colour

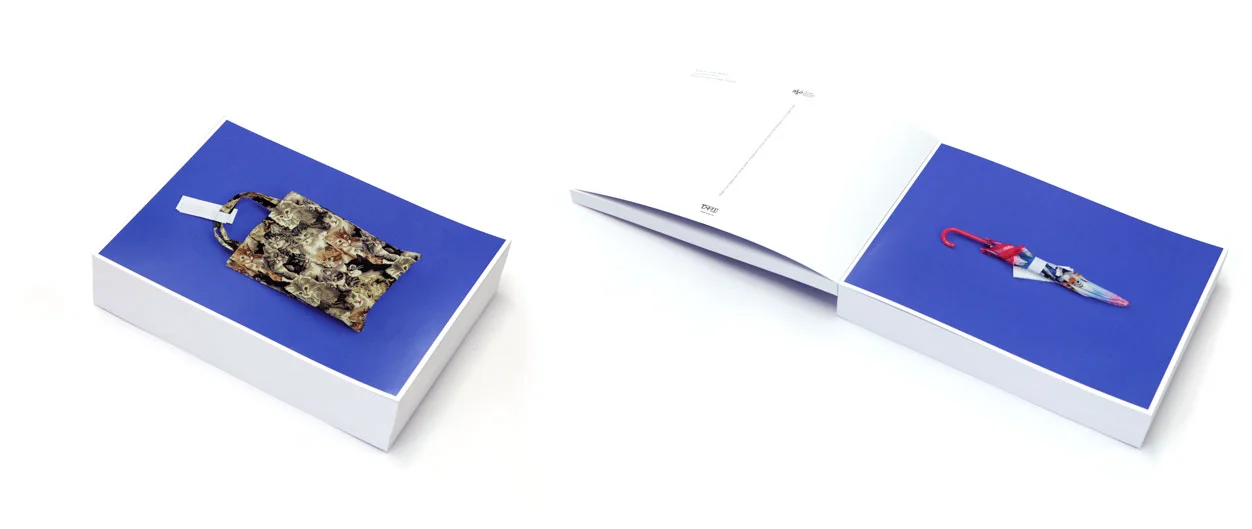

ARTISTS BOOKS (EDITIONS)

- 2025

- 2 Tonnen Kalkstein

Kunstraum IDEAL (Hg.)

Edition: 5

Archiv-Lesebuch (ChatGPT)

Kunstraum IDEAL (Hg.)

Edition: 5

Drugi Spomenik / Das andere Denkmal

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch mit Jakob Holzer (Hg.), Wien

unlimitiert - 2021

- Roxy, 27.05.2021 (Block Beuys)

Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt (Hg.),

Edition: 10+2 - 2020

- Unplugged

David Korecky, Galerie Rudolfinum (eds.), Prague

Edition: 99 - 2018

- Lost and Found

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 8+2 - 2016

- Fotoarchiv 30.06.2016-26.04.2015

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2 - 2015

- Fotoarchiv 26.04.2015-06.05.2014

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2 - 2014

- Das Meer der Stille

Landesgalerie Linz / Barbara Schröder (eds.), Linz

Fotoarchiv 14.04.2014-10.07.2012

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2 - 2012

- Aussicht kann durch Ladung verstellt sein

Kunstverein Medienturm (eds.), Graz

Edition: 20+2

Fotoarchiv 20.04.2012-09.03.2010

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2 - 2011

- Raum für 17 Minuten 6’23

Galerie im Taxispalais (eds.), Innsbruck - 2010

- Atlas

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch, Secession (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2

Fotoarchiv 20.02.2010-17.10.2009

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2

Innere Grenze

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 3+2 - 2009

- Fotoarchiv 28.09.2009-7.10.2008

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2 - 2008

- Fotoarchiv 05.10.2008-16.02.2007

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2 - 2007

- Fotoarchiv 21.01.2007-07.09.2005

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2 - 2005

- Fotoarchiv 16.08.2005-04.08.2004

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2 - 2004

- Fotoarchiv 06.06.2004-15.02.2001

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2

Raumbuch

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 3+2

FILME

- 2025

- Drugi spomenik / Das andere Denkmal

Video, 1 Kanal

32 min 22 sec

Ton, Farbe - 2024

- Seemeile (Sumbu und Pekel)

Video, 1 Kanal

20 min 49 sec

Ton, Farbe

Die Reise der Bilder

Video, 8 Kanal

24 min 24 sec - 33min 23 sec, Ton, Farbe - 2023

- Lueger Temporär

Video, 1 Kanal

22 min 11 sec, Ton, Farbe

05.01.2023 (Pečnikov travnik/Pečnik-Wiese)

Video, 4 Kanal

1h 50min, Ton, Farbe - 2021

- Pilot

(Dialogisch den Horizont expandieren

- von Klagenfurt nach Klagenfurt)

Video, 1 Kanal

11 min 08 sec, Ton, Farbe

Roxy, 27.05.2021 (Block Beuys)

Video, 1 Kanal

8 min 12 sec, Ton, Farbe - 2020

- Parallel Worlds

20.03.2020 / 01.04.2020 / 20.04.2020

Video, 3 Kanal

23 min 12sec, Ton, Farbe - 2017

- Ohne Titel (Albaner Hafen)

Video

3 Kanal Projektion

51 min, Farbe, Ton - 2015

- Das Denkmal

Video

2 Kanal Projektion

130 min, Farbe, Ton - 2014

- Raum für 5’16’’

Video

2 Kanal Projektion

5 min 16 sec, Farbe, Ton

Das Meer der Stille

Video

3 min 34 sec, Farbe, Ton - 2011

- Raum für 17 Minuten 6’23’’

Video

2 Kanal Projektion

6 min 23 sec, Farbe, Ton - 2009

- Das menschliche und das tierische Wesen

Video

5 Kanal Projektion

19 min, Farbe, Ton - 2007

- Ohne Titel, 12 Bauten von Peter Zumthor

Video

6 Kanal Projektion

480 min, Farbe, Ton

Nebel

Video auf DVD

30 min, Farbe, Ton - 2005

- Ohne Titel, Kunsthaus Bregenz

Video auf DVD

6 Kanal Projektion

72 h, Farbe, Ton

I’m too tired to tell you

Video auf DVD

17 min, Farbe, ohne Ton - 2004

- Longitude / Latitude

Video auf DVD

77 min, Farbe, ohne Ton

Raum

Video auf DVD

60 min, Farbe, Ton - 2003

- Camera dead

Video auf DVD

35 sec, Farbe, Ton

Räumliche Maßnahme (2)

Video auf DVD

2 Kanal Projektion

50 min, Farbe, Ton - 2002

- Räumliche Maßnahme (1)

Video auf DVD

28 min, Farbe, Ton

ARTISTS BOOKS (EDITIONS)

- 2025

- 2 Tonnen Kalkstein

Kunstraum IDEAL (Hg.)

Edition: 5

Archiv-Lesebuch (ChatGPT)

Kunstraum IDEAL (Hg.)

Edition: 5

Drugi Spomenik / Das andere Denkmal

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch mit Jakob Holzer (Hg.), Wien

unlimitiert - 2021

- Roxy, 27.05.2021 (Block Beuys)

Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt (Hg.),

Edition: 10+2 - 2020

- Unplugged

David Korecky, Galerie Rudolfinum (Hg.), Prag

Edition: 99 - 2018

- Lost and Found

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 8+2 - 2016

- Fotoarchiv 30.06.2016-26.04.2015

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2 - 2015

- Fotoarchiv 26.04.2015-06.05.2014

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2 - 2014

- Das Meer der Stille

Landesgalerie Linz / Barbara Schröder (Hg.), Linz

Fotoarchiv 14.04.2014-10.07.2012

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2 - 2012

- Aussicht kann durch Ladung verstellt sein

Kunstverein Medienturm (Hg.), Graz

Edition: 20+2

Fotoarchiv 20.04.2012-09.03.2010

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2 - 2011

- Raum für 17 Minuten 6’23

Galerie im Taxispalais (Hg.), Innsbruck - 2010

- Atlas

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch, Secession (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2

Fotoarchiv 20.02.2010-17.10.2009

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2

Innere Grenze

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 3+2 - 2009

- Fotoarchiv 28.09.2009-7.10.2008

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2 - 2008

- Fotoarchiv 05.10.2008-16.02.2007

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2 - 2007

- Fotoarchiv 21.01.2007-07.09.2005

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2 - 2005

- Fotoarchiv 16.08.2005-04.08.2004

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2 - 2004

- Fotoarchiv 06.06.2004-15.02.2001

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2

Raumbuch

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 3+2

Nicole Six and Paul Petritsch have been realizing films, photographs, displays, artist books as well as site- and context-specific installations and projects in public space since 1997. They live in Vienna.

They explore the limits of our existence and our perception with expeditions into everyday life, through oceans, polar regions, concrete deserts as well as lunar landscapes. With their experimental test arrangements and interventions, they locate themselves and the viewer again and again in art spaces, architectures and landscapes.

BIOGRAPHY

Nicole Six

Born 1971 in Vöcklabruck, Austria

Academy of fine Arts Vienna, Sculpture

Paul Petritsch

Born 1968 in Friesach, Austria

University of Applied Arts Vienna, Architecture

1997 MAK Schindler Scholarship, Los Angeles

2004 International Studio & Curatorial Program / ISCP, New York

2005 Visiting Professor at Experimental Design, Kunstuniversität Linz

2006 State Fellowship for Fine Arts

2007 Kardinal König Art Award

2008 T-mobile Art Award

2008 Lectureship Modul Kunsttransfer, Institut für Kunst und Gestaltung, Vienna

2009 Austrian drawing Award

2011 - 2020 Member of the panel BIG Art – Kunst und Bau der BIG (Nicole Six)

2014 since 2014 Head of the Department Site-Specific Art, University of Applied Arts Vienna (Paul Petritsch)

2015 Member of the panel Kunsthalle Exnergasse (Paul Petritsch)

2017 Karl-Anton-Wolf-Award

2019 since 2019 board member of Camera Austria, Graz (Nicole Six)

2021 Guest professor of the Department Site-Specific Art, University of Applied Arts Vienna (Nicole Six)

2023 Lectureship at the department Kunst und Musik, Kunst und Kunsttheorie, University of Cologne (Nicole Six)

2023 Landeskulturpreis für Bildende Kunst, Upper Austria

2024 board member of Camera Austria, Graz (Nicole Six)

Landeskulturpreis für Bildende Kunst, Lower Austria

Collaboration since 1997

KONTAKT

Nicole Six and Paul Petritsch

Schottenfeldgasse 76/25

1070 Vienna/Austria

Tel. +43 1 95797 99

Fax +43 1 95797 99

Mail: office@six-petritsch.com

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch realisieren seit 1997 gemeinsam Filme, Fotografien, Displays, Künstlerbücher sowie orts- und kontextspezifische Installationen und Projekte im öffentlichen Raum. Sie leben in Wien.

Die Grenzen unseres Daseins und unserer Wahrnehmung erforschen sie mit Expeditionen in den Alltag, durch Ozeane, Polarregionen, Betonwüsten, wie auch Mondlandschaften. Mit ihren experimentellen Versuchsanordnungen und Eingriffen verorten sie sich und die Betrachter*innen immer wieder neu in Kunsträumen, Architekturen und auch Landschaften.

BIOGRAFIE

Nicole Six

1971 geboren in Vöcklabruck, Österreich

Studium der Bildhauerei an der Akademie der bildenden Künste

Paul Petritsch

1968 geboren in Friesach, Österreich

Studium der Architektur an der Universität für Angewandte Kunst

1997 Schindlerstipendium

2004 ISCP, New York

2005 Gastprofessur am Institut für Experimentelle Gestaltung, Kunstuni Linz

2006 Staatsstipendium für bildende Kunst

2007 Kardinal König Kunstpreis

2008 T-mobile Art Award

2008 Lehrauftrag Modul Kunsttransfer, Institut für Kunst und Gestaltung, TU Wien

2009 Österreichischer Grafikwettbewerb

2011 - 2020 Jurymitglied von BIG Art – Kunst und Bau der BIG (Nicole Six)

2014 seit 2014 Leitung Abteilung für ortsbezogene Kunst, Universität für Angewandte Kunst (Paul Petritsch)

2015 Künstlerischer Beirat der Kunsthalle Exnergasse (Paul Petritsch)

2017 Karl-Anton-Wolf-Preis

2019 seit 2019 Vorstandsmitglied der Camera Austria, Graz (Nicole Six)

2021 Gastprofessorin Abteilung für ortsbezogene Kunst, Universität für Angewandte Kunst (Nicole Six)

2023 Lehrauftrag am Department Kunst und Musik, Kunst und Kunsttheorie, Universität zu Köln (Nicole Six)

2023 Landeskulturpreis für Bildende Kunst, Oberösterreich

2024 Vorstandsmitglied der Camera Austria, Graz (Nicole Six)

Landeskulturpreis für Bildende Kunst, Niederösterreich

Zusammenarbeit seit 1997

KONTAKT

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch

Schottenfeldgasse 76/25

1070 Wien/Österreich

Tel. +43 1 95797 99

Fax +43 1 95797 99

Mail: office@six-petritsch.com

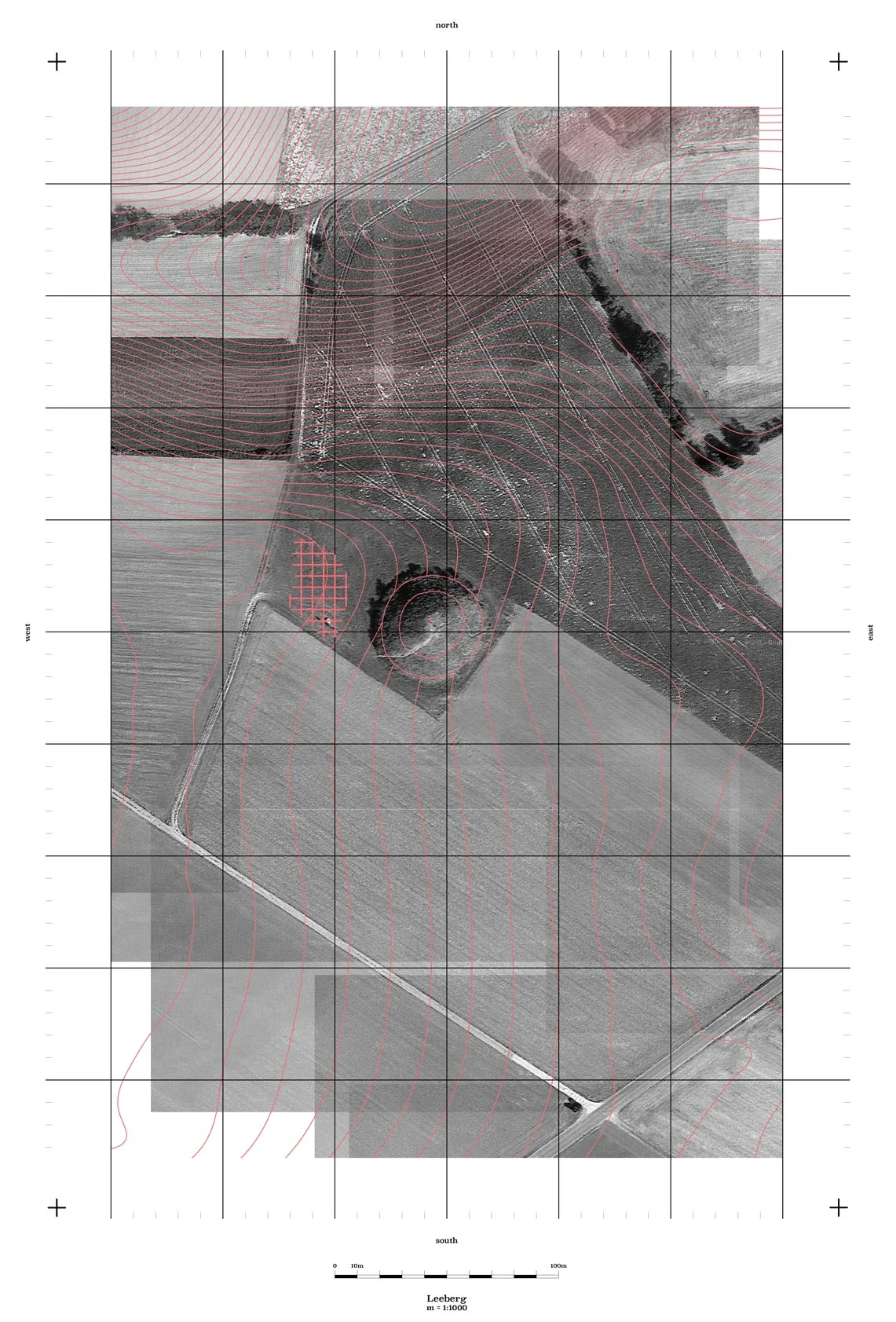

Footnotes in the Landscape

Project for the preservation of a tumulus

The tumulus (burial mound) near Großmugl was not only recently heralded by astronomers as a great spot for stargazing, but more and more people have been wanting to make it a world heritage site, with the result that an increasing number of visitors have come to see the tumulus. Although it is an archeological monument and therefore protected,¬ Archaeologists are now worried about visitors walking on top of it and that this is beginning to make it deteriorate.

The tumulus is roughly 2,500 years old. It is about 16 meters high and is one of the largest of its kind in Central Europe. It not only lent the town its name; it is a key element of the region’s identity. It is also extremely valuable from a scientific point of view, because the mound’s form and contents are still intact. Archeologists have deliberately refrained from conducting an excavation of the site to this day. Also, because it is so steep and dry, the tumulus is covered with Pannonian dry grassland, which is rare in this area.

The tumulus could be regarded as a kind of time capsule surrounded by an environment that is defined by agriculture. It is a place now caught up in a conflict between preservation, protection and promotion. As such, it could also serve as an example of the current discussion on how people can treat their environment sustainably.

As a way of doing justice to the various demands related to the tumulus, and to inform people that they are not allowed to climb up the burial mound, Nicole Six and Paul Petritsch came up with a project that abstained from architectural plans. Instead, they proposed a campaign that merged the language and interests of everyone involved: archeologists, local inhabitants, farmers, astronomers, and astrophotographers. The intervention was meant to consist of text panels that would not only accompany the visitors along the path to the tumulus, but also act as guides that inform them about different issues, like the history of the site, its archeology, its identity-forming value, its function as a stargazing spot, and its preservation as a monument. The text panels would be variable and inserted firmly in the ground with the idea of being able to expand on or change the field of information created in this way any time.

The text panels were to serve as footnotes in the landscape and focus on the visitors, helping to convey content to them. They were meant to explain to visitors that they should not climb the tumulus as a way of protecting it. The path to the tumulus would thus become a mindful experience and create a space to illustrate the multifarious connections between the tumulus, the landscape, and humans—everyone would be addressed.

Nicole Six and Paul Petritsch with Florian Hofer

Fußnoten in der Landschaft

Projekt zum Schutz eines Hügelgrabs

Seit das Hügelgrab bei Grossmugl von Astronomen als Sternlichtoase beworben wird und der Wunsch besteht, den Ort zum Weltkulturerbe zumachen, gibt es am Tumulus eine gesteigerte BesucherInnenfrequenz. Die Archäologen beklagen eine beginnende Zerstörung durch das Begehen von BesucherInnen obwohl das Hügelgrab als Bodendenkmal unter Schutz steht.

Der Tumulus, ca. 2500 Jahre alt und mit ca. 16 m Metern Höhe einer der größeren Mitteleuropas, ist Namensgeber für die Gemeinde und für die Region ein identitätsstiftender Faktor. Er ist aus wissenschaftlicher Sicht von hohem Wert, da sowohl die Form des Hügels als auch sein Inhalt intakt sind: Bis heute haben Archäologen bewusst von einer Grabung Abstand genommen. Der Hügel ist zudem aufgrund seiner Steilheit und Trockenheit mit dem hier seltenen, pannonischen Trockenrasen bewachsen.

Der Grabhügel kann als eine Zeitkapsel in einer von Landwirtschaft geprägten Umgebung betrachtet werden. Dieser Ort steht nun in einem Konflikt zwischen Erhaltung, Schutz und Bewerbung. Er kann auch beispielhaft für die aktuelle Diskussion um den nachhaltigen Umgang des Menschen mit seiner Umwelt gesehen werden.

Um den unterschiedlichen Begehren, die mit dem Hügelgrab zusammenhängen, gerecht zu werden, und das Verbot das Hügelgrab zu besteigen zu kommunizieren, verzichten Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch vorerst auf bauliche Konzepte. Sie schlugen eine Kampagne vor, die die Sprache und Interessen aller Akteure sammelt: Archäologen, AnwohnerInnen, Landwirte, Astronomen und Astrofotografen. Die Intervention besteht aus Texttafeln, die den Besucher am Weg zum Tumulus nicht nur begleiten, sondern auch anleiten und über verschiedenen Themen informieren: Geschichte des Ortes, Archäologie, Wert als Identifikationsfaktor, Sternlichtoase, Denkmalschutz. Die Texttafeln sind flexibel konzipiert und werden in die Erde gesteckt. Die Idee ist, das so entstandene Feld an Informationen jederzeit erweitern oder verändern zu können.

Die Texttafeln fungieren als Fußnoten in der Landschaft. Sie stellen den BesucherInnen ins Zentrum und helfen Inhalte zu vermitteln. Sie verankern den Wunsch, das Hügelgrab zu seinem Schutz nicht zu besteigen. Der Weg zum Tumulus wird zu einem bewussten Erlebnis, es wird ein Raum hergestellt, der die vielfältigen Beziehungen zwischen Tumulus, Landschaft und Menschen veranschaulicht. Jede und Jeder ist angesprochen.

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch mit Florian Hofer

The Vienna Art Book Fair is pleased to host several exhibitions at this year’s event. Marlene Obermayer invited professionals in the field of art and culture to curate exhibitions on artists’ books, “publishing as artistic practice” and publications that utilized special distribution mechanisms.

Curated by: Annette Gilbert, Bernhard Cella, Christian Egger, David Jourdan, Franz Thalmair, Grudrun Ratzinger, Heimo Zobernig, Jan Steinbach, Johannes Porsch, Jürgen Dehm, Luca Lo Pinto, Moritz Grünke, Nicole Six/Paul Petritsch and Regine Ehleiter

Die Wiener Kunstbuchmesse präsentiert in diesem Jahr mehrere Ausstellungen. Marlene Obermayer lud Fachleute aus dem Bereich Kunst und Kultur ein, Ausstellungen zu Künstlerbüchern, „Publizieren als künstlerische Praxis“ und Publikationen mit speziellen Verbreitungsmechanismen zu kuratieren.

Kuratiert von: Annette Gilbert, Bernhard Cella, Christian Egger, David Jourdan, Franz Thalmair, Grudrun Ratzinger, Heimo Zobernig, Jan Steinbach, Johannes Porsch, Jürgen Dehm, Luca Lo Pinto, Moritz Grünke, Nicole Six/Paul Petritsch und Regine Ehleiter

A person stands on the ice and breaks a hole in the frozen surface, determinedly swinging the pick axe again and again. A dark and indistinct figure against the nebulous horizon. We sense that its ambition is about to backfire. A hardly spectacular act, absurd and dangerous nevertheless. What is this person looking for? What does it hope to uncover? Is it forging a path to somewhere?

Strongly sensuous qualities emanate from the tension between the solitary figure, its irrational activity, and the eeriness of the seemingly infinite natural setting evoked by the lack of a horizon and the wispy fog. This sublimity is disrupted by human activity. The figure is not working against nature; rather, it is intent on bringing about its own destruction. We as viewers are witnessing a deliberate disappearance. Ultimately, the hole in the ice will become a kind of window leading out of the image space, out of the video. Into the black void.

Eine Person steht auf der Eisfläche und schlägt ein Loch. Unbeirrt holt sie immer wieder mit ihrer Spitzhacke aus. Sie hebt sich dunkel vom nebligen Horizont ab. Sie wird sich - so ahnt man bald - ganz real selbst den Boden unter den Füßen wegziehen. Als Aktion nicht spektakulär, jedoch aberwitzig und gefährlich. Was sucht sie? Was will sie freilegen? Wohin vorstoßen?

Die Spannung zwischen dem Einsamen, ihrer widersinnigen Handlung und der durch den fehlenden Horizont und leichten Nebel gespenstisch unendlich erscheinenden Natur verbreitet enorme sinnliche Qualitäten. Diese Erhabenheit wird durch das menschliche Verhalten gestört. Zwar arbeitet sie nicht gegen die Natur, aber sie betreibt konzentriert den eigenen Untergang. Wir als Betrachter werden Zeugen eines vorsätzlichen Verschwindens. Das Loch im Eis wird am Ende auch eine Art Fenster hinaus aus dem Bildraum, aus dem Video. Ins schwarze Nichts.

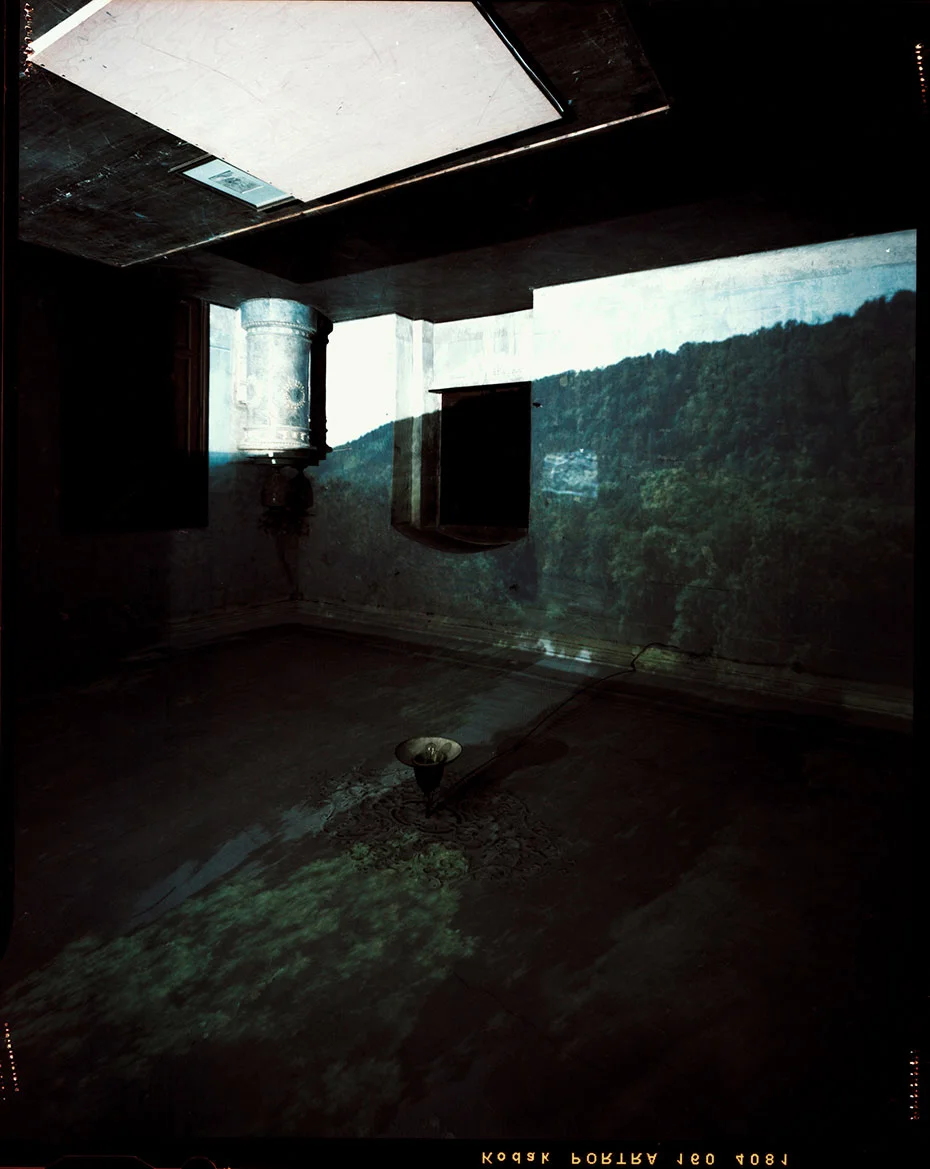

Norden, Süden, Osten, Westen

Nicole Six and Paul Petritsch´s work at Buchberg began with an in-depth spatial examination with regard to the axes of the castle, including a topographic exploration of the surroundings of the building. In what can be described as a ‘concentrated, closed situation’ (Six/Petritsch) and by resorting to photography, the artists eventually condensed the huge dimensions of their experiment by linking it to the morethan 2000-year-old principle of the camera obscura. At each of four points in the castle facing north, east, south, and west, they installed a camera obscura in a darkened room, its image falling in from the outside—mirrorinverted and upside down—overlapping with the interior space and exhibiting ascertainable details frequently giving a technoid impression on the one hand and revealing pictorially poetic moments on the other, which Six/Petritsch captured as photographs. These have now been installed in three rooms of the castle. In the pictures, the wide expanse of the exterior seems to correspond with the seclusion of the interiors; similarly, the camera obscura was once considered a private and place of retreat and contemplation of the world that harboured a huge experimental potential.

Norden, Süden, Osten, Westen

Am Beginn der Arbeit von Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch in Buchberg stand eine umfassende Raumuntersuchung in Bezug auf die Achsen des Schlosses mit einer topographischen Erkundung der Umgebung des Gebäudes. Mit einem Rekurs auf die Fotografie in eine „konzentrierte, geschlossene Situation“ (Six/Petritsch) haben die Künstler das weite Versuchsfeld schließlich verdichtet und mit dem über 2000 Jahre alten Prinzip der Camera Obscura verbunden. An vier Punkten im Schloss, die jeweils nach Norden, Osten, Süden und Westen orientiert waren, installierten sie in abgedunkelten Räumen eine Camera Obscura, deren von außen einfallendes Bild sich – seitenverkehrt und am Kopf stehend – mit dem Innenraum überlagerte und einerseits registrarisch erfassbare, oft technoid wirkende Details erkennen ließ, andererseits bildhafte poetische Momente hervorbrachte, die Six/Petritsch als Fotografien festhielten. Sie sind nun auf drei Räume im Schloss verteilt. In den Bildern scheint die Weite des Außenraums mit der Abgeschlossenheit der Innenräume zu korrespondieren, wie die Camera Obscura ehemals als ein privater Ort von Rückzug und Weltbetrachtung angesehen wurde, der ein großes experimentelles Potential in sich birgt.

Lost and Found

Sometimes things get left behind in trains; sometimes things from history get left behind. “Lost and Found” by Six/Petritsch draws a remarkable connection between the Lost & Found offices of the Austrian Railways (ÖBB) and the House of Austrian History (HdGÖ): Both deal with objects that have their own special stories, stories written by life. Who decides which items are worthless and which have meaning?

Monika Sommer, Haus der Geschichte Österreich (HdGÖ)

Lost and Found

Manchmal bleiben Dinge in Zügen zurück, manchmal werden Dinge von der Geschichte zurückgelassen. "Lost and Found" von Six / Petritsch stellt eine außergewöhnliche Beziehung zwischen dem ÖBB-Fundbüro Lost & Found und dem Haus der Geschichte Österreich her: Beide haben es mit Dingen zu tun, die ihre besondere Geschichten haben, Geschichten, die vom Leben geschrieben wurden. Wer entscheidet, welche Dinge wertlos sind und welche Bedeutung tragen?

Monika Sommer, Haus der Geschichte Österreich

Gab es jemals in Ihrem Leben einen Gegenstand, der Ihnen so teuer war, dass Sie ihn niemals aufgeben wollten? War er Ihnen so wichtig, dass Sie ihn am liebsten im Tresor aufbewahren oder in die Sammlung Ihres Privatmuseums aufnehmen wollten? Und hatten Sie das Pech, dass er Ihnen verloren ging oder gestohlen wurde? Wenn ja, sind Sie hier richtig. Wenn nicht, dann ebenfalls. Willkommen in der Ausstellung Lost and Found, die von Nicole Six & Paul Petritsch für den Kunst-Zug TRAM gestaltet wurde. Charakteristisch für das Künstlerduo ist sein sensibler Umgang mit dem Umfeld in ortsspezifischen und kontextsensitiven Installationen.

Derzeit entsteht in Wien ein neues Museum, das Haus der Geschichte Österreich, in dem Sie die bedeutsamen Objekte aus Ihrer Vergangenheit vielleicht finden. Wenn nicht, können Sie sich ans Fundbüro wenden. Nicole Six & Paul Petritsch zeigen Gegenstände, die in Zügen und auf Bahnhöfen verloren gingen und gefunden wurden, in unauffälliger Konfrontation mit Museumsexponaten. Auf der einen Seite ein Gegenstand, der jemanden abhandengekommen ist und vielleicht nie mehr seinem Daseinszweck zugeführt werden kann, auf der anderen Seite ein Artefakt, das gesetzlich geschützt und in einem Depot des Museums in der Wiener Hofburg eingeschlossen ist. Ein Gegenstand, der seinen Besitzer und seine Geschichte verloren hat, in Konfrontation mit einem Exponat mit dokumentierter Geschichte. Ausgelöschte Erinnerung versus zeit- und ortsspezifisches Erinnerungsstück. Was haben Sie heute im Zug vergessen?

Juraj Čarný, TRAM Train Gallery and Cultural Center

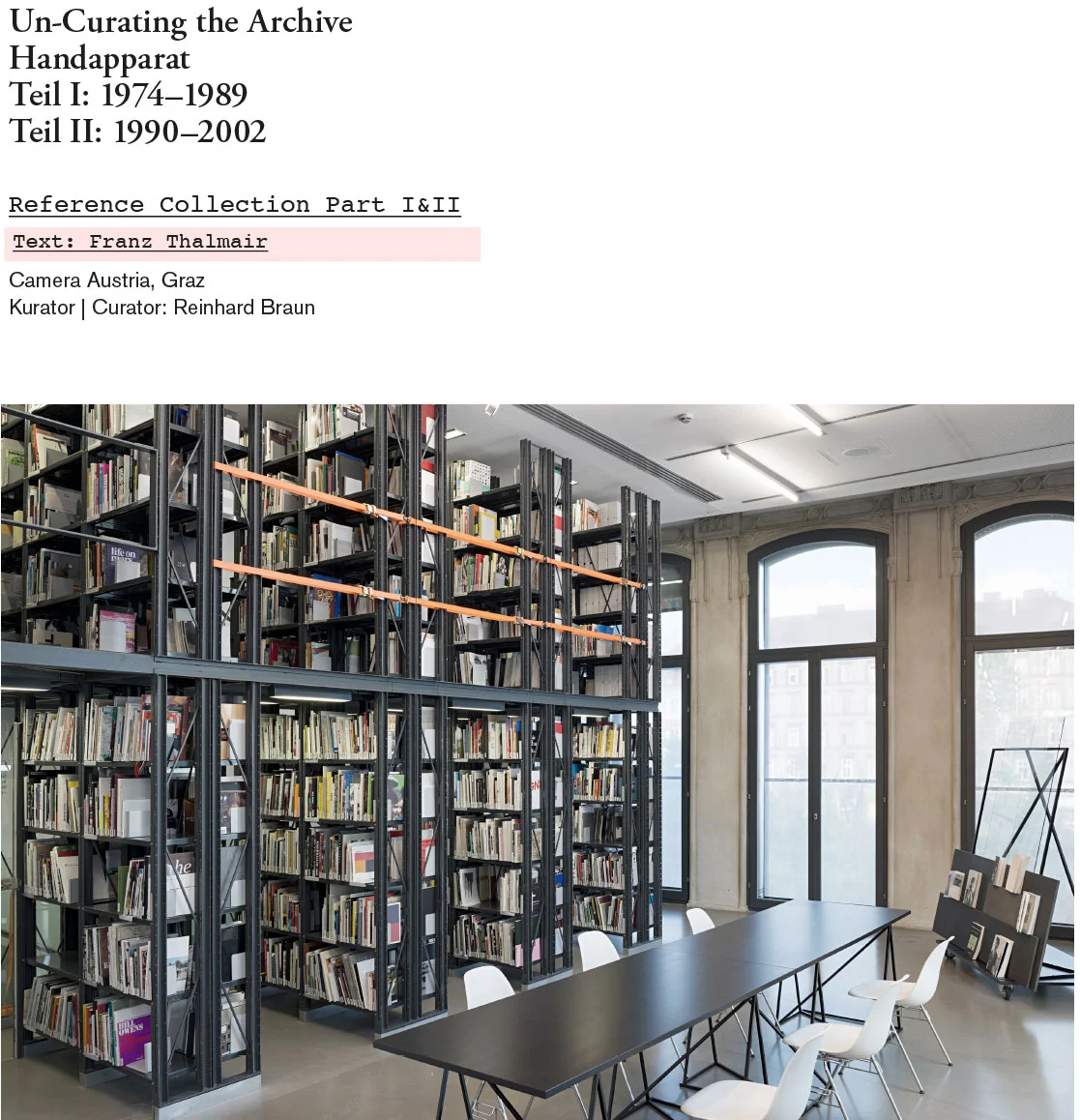

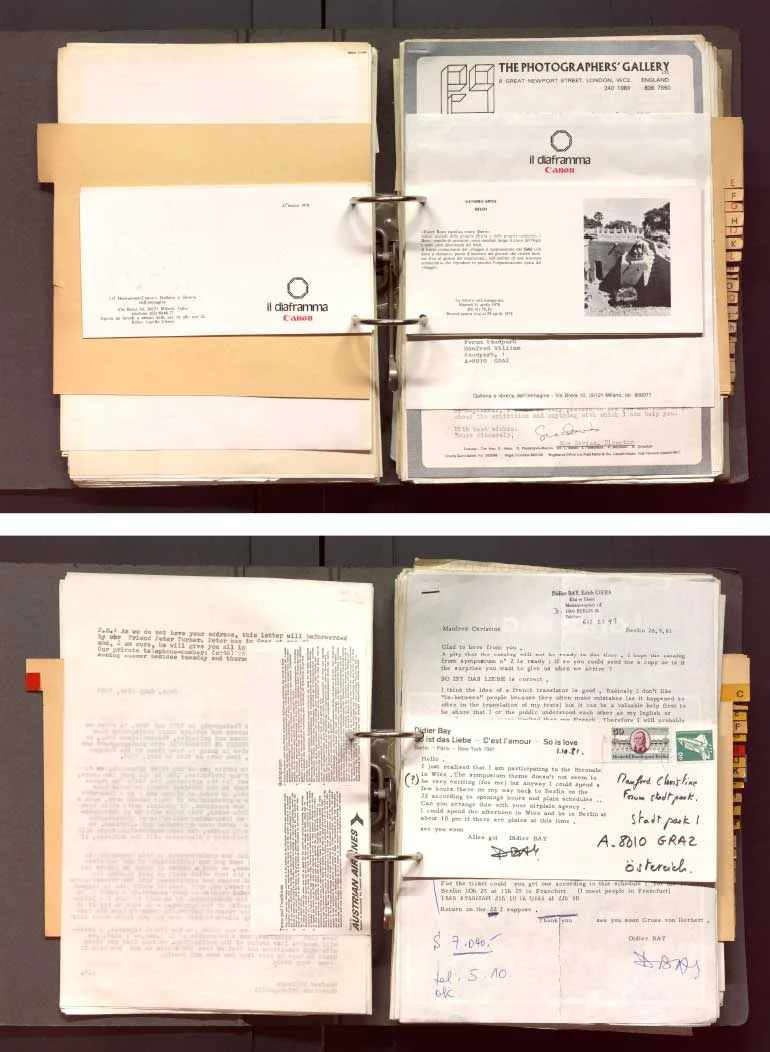

Un-Curating the Archive

Handapparat, 2017

Binder for binder, page for page, document for document. In Un-Curating the Archive Nicole Six and Paul Petritsch have digitized Camera Austria’s entire archive including each at first glance seemingly insignificant detail – then printed and bound this material in its found arrangement, and presented the books in the exhibition space according to the original ordering criteria. Everything. Countless data, numbers, correspondences, notes, invitation cards, research findings, lists of items, exhibition ideas, and loan contracts from 1974 to 1989, all this was barely processed by Six/Petritsch. And yet much has changed through the artist duo’s intervention into the archive of an exhibition-space-and-storeroom hybrid, of an institution whose focus lies in the field of photography and which has itself through its activity inscribed itself in countless archives and libraries.

“Un-curating” is how the artist duo describes what it is doing and at the same time not doing with this accumulation of binders, with this more or less already structured stack of notes: a viewing of the material, a putting into form, a preparing and making available, a selecting and showing. For Un-Curating the Archive, for this hybrid form of research, intervention, and installation, the artists have selected everything and brought everything together using the medium of the exhibition. What we therefore have here is a special form of curatorial practice, a curatorial sphere of action that conceives the exhibition not only as a means of presenting an experimental or research process but also as the site of the actual research, or in the words of the curator Simon Sheikh: “The curatorial project—including its most dominant form, the exhibition—should thus not only be thought of as a form of mediation of research but also as a site for carrying out this research, as a place for enacted research. Research is not only that which comes before realisation but also that which is realised throughout actualisation. That which would otherwise be thought of as formal means of transmitting knowledge—such as design structures, display models and perceptual experiments—is here an integral part of the curatorial mode of address, its content production, its proposition.”[1] Un-Curating the Archive does not stop at reflecting on sociopolitical factors and conveying the artistic questions and photographic themes that have been addressed by Camera Austria since its founding. The working in and working with a corpus whose potential still lies dormant is the underlying motivation behind making the found material available in its entirety.

With each examination of the Camera Austria archive, a new narration, a new journal article, a new exhibition might be developed from the collection of data: stories about artistic spheres of action and biographies, stories about the digitization process of photography since the mid 1970s, stories about the connections and relationships between the people involved – stories extracted in an exhibition that as such can only inadequately reproduce what makes an institution like Camera Austria what it is. In Un-Curating the Archive Nicole Six and Paul Petritsch confront such a decision between entire view and detail – between macro and micro photograph – and in the same moment they avoid it by withholding their books from the viewer, depriving the readers of the reproduced archivalia. This applies not only to a subjective thematic selection or a supposedly objective overview of the material; Six/Petritsch go a step further. By making available their entire research instrumentarium, their tools, the artists give the viewers the chance to extract their own stories from the reproduced materials, develop their own questions, interpret their own connections, ultimately letting each viewer produce his or her own story of an institution. This fundamental performative aspect under which artistic spheres of action like those of Un-Curating the Archive can be grouped are described by Hanne Seitz as follows: “The research aim wants neither to capture reality in images nor describe it in words, neither to test hypotheses nor let itself be guided by preconceived questions, nor does it intend to document any processes. It wants to be identical with the practice itself, to activate implied knowledge and generate new information in processing, applying, and handling this practice […] – Research in the field of art which, while being conducted, provides knowledge and absolutely sheds light on habitualized inscriptions”[2] Thus, binder for binder, page for page, document for document Un-Curating the Archive reveals an institution to the viewer– a potential waiting to be discovered, tapped, and fully exhausted, a potential space that the artist duo has turned into the actual protagonist of its work.

Nicole Six and Paul Petritsch have created a 1:1 scale digitization of the archive, bound it, and put it on display. What viewers, however, are presented with in Un-Curating the Archive as an installation with books, tables, a display stand, and a spatial intervention can no longer be considered an archive because the process of the simple but complete reproduction of all data has transformed the loose conglomeration of Camera Austria’s correspondences, notes, invitation cards, lists of items, and other documents and papers from an archive into a library. If we differentiate between archive and library, the biggest distinction between the two institutions lies in the items of the collection: “the library contains works, in other words inherently ordered artifacts and data storage mediums which were created to remember. The archive, in contrast, compiles unprocessed objects, which have in no way been created to remember, ‘raw’ data, ‘unmediated’ past, the real.”[3]

But while Six/Petritsch use the existing order of the archive materials to create a superordinate structure for their library, the material density and the intransparency of the archive in Un-Curating the Archive remains intact – a staging through which the intervention becomes an artistic work. In the end, in a way analogous to Camera Austria, to this cross between exhibition space and storeroom, the installation may also be seen as a hybrid that defies more precise ascriptions: a manifestation of a curatorial practice, in which the gestures of selection and presentation are overstylized; a complete collection of data of an institution that starts to unravel at the moment of reduplication; a photographic work whose goal is the medium of the book – an archive that has become a library. If one were to reduce Un-Curating the Archive despite all its ambiguity to a buzzword, the first concept that would come to mind might be the librarchive.

[1] Sheikh, Simon: Towards The Exhibition As Research, in: O‘Neill, Paul; Mick Wilson (ed.): “Curating and Research”, London / Amsterdam: Open Editions / de Appel, 2015, 32–46, here: 40.

[2] Seitz, Hanne: Performative Research, in: Kulturelle Bildung Online, https://www.kubi-online.de/artikel/performative-research (last accessed: 8/15/2018).

[3] Ebeling, Knut: Wilde Archäologien 2. Begriffe der Materialität der Zeit – von Archiv bis Zerstörung, Berlin: Kadmos, 2016, 21.

Translation: Kimi Lum

Un-Curating the Archive

Handapparat, 2017

Ordner für Ordner, Seite für Seite, Dokument für Dokument. In Un-Curating the Archive haben Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch jedes auf den ersten Blick noch so unwichtig erscheinende Detail des Archivs der Camera Austria digitalisiert – und danach ausgedruckt, in der vorgefundenen Reihenfolge zu Büchern gebunden und schließlich den ursprünglichen Ordnungskriterien folgend im Ausstellungsraum präsentiert. Alles. Unzählige Daten, Zahlen, Korrespondenzen, Notizen, Einladungskarten, Ergebnisse von Recherchen, Stücklisten, Ausstellungsideen und Leihverträge aus den Jahren 1974 bis 1989, all dies haben Six/Petritsch kaum bearbeitet. Und doch hat sich vieles verändert durch ihre Intervention in das Archiv eines Hybrids aus Kunstmagazin und Ausstellungsraum, einer Institution, deren Augenmerk im Feld der Fotografie liegt und die sich über ihre Tätigkeit selbst in unzählige Archive und Bibliotheken eingeschrieben hat.

Als „un-curating“ bezeichnen die beiden Kunstschaffenden, was sie mit der Ansammlung von Ordnern, mit diesem mehr oder weniger vorstrukturierten Zettelhaufen, tun und gleichzeitig nicht tun: Material sichten, in Form bringen, bereitstellen und verfügbar machen, auswählen, zeigen. Das Künstlerduo hat für Un-Curating the Archive , für diese Mischform aus Recherche, Intervention und Installation, alles ausgewählt und ebenso alles im Medium der Ausstellung zusammenführt. Wir haben es also hier mit einer besonderen kuratorischen Praxis zu tun. Mit einem Handlungsfeld nämlich, das die Ausstellung nicht nur als Mittel zur Präsentation eines Untersuchungs- oder Forschungsprozesses, sondern als Ort der eigentlichen Recherche begreift, wie es der Kurator Simon Sheikh formuliert: „Das kuratorische Projekt – mit seiner dominanten Form, der Ausstellung – sollte daher nicht nur als eine Form der Forschungsvermittlung verstanden werden, sondern auch als ein Ort der Durchführung der Forschung, als ein Ort der aufgeführten Forschung. Forschung ist nicht nur das, was vor der Realisierung kommt, sondern auch das, was während der Aktualisierung realisiert wird. Was ansonsten als formales Mittel zur Wissensvermittlung gedacht wäre – wie Designstrukturen, Anschauungsmodelle und Wahrnehmungsexperimente – ist hier integraler Bestandteil des kuratorischen Handlungsmodus, seiner Inhaltsproduktion, seiner Vorschläge.“[1] Nicht nur die Reflexion gesellschaftspolitischer Gegebenheiten, nicht nur die Vermittlung von künstlerischen Fragestellungen und fotografischen Themenfeldern wie sie auch von der Camera Austria seit ihrer Gründung bearbeitet werden, stehen bei Un-Curating the Archive im Vordergrund. Sondern das Handeln in einem und das Handeln mit einem Corpus, dessen Potenzial bis dato brachgelegen hat, steckt als Motivation hinter dem Verfügbarmachen des vorgefundenen Materials in seiner Gesamtheit.

Mit jedem Blick in das Archiv der Camera Austria ließe sich aus der Datensammlung eine neue Narration, ein neuer Zeitschriftenartikel, eine neue Ausstellung entwickeln: Geschichten über künstlerische Handlungsfelder und Biografien, Geschichten über den Digitalisierungsprozess der Fotografie seit Mitte der 1970er-Jahre, Geschichten über Verbindungen und Beziehungen zwischen den handelnden Personen – Geschichten, die extrahiert in einer Ausstellung nur unzureichend wiedergegeben können, was eine Institution wie die Camera Austria ausmacht. Einer solchen Entscheidung zwischen Gesamtbild und Detailaufnahme, zwischen Makro- und Mikrofotografie, stellen sich Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch mit Un-Curating the Archive und entziehen sich ihr im selben Moment. Denn sie enthalten den Betrachter_innen ihrer Bücher, den Leser_innen der reproduzierten Archivalia, nicht nur eine subjektive thematische Auswahl oder einen vermeintlich objektiven Überblick über das Material vor, sondern sie gehen einen Schritt darüber hinaus. Indem das Künstlerduo sein Rechercheinstrumentarium, sein Werkzeug, zur Gänze zur Verfügung stellt, haben Betrachter_innen die Möglichkeit, eigene Geschichten aus den reproduzierten Materialien zu schälen, eigene Fragestellungen zu entwickeln, eigene Verbindungslinien abzulesen und nicht zuletzt die eigene Geschichte einer Institution herzustellen. Diesen grundlegenden performativen Aspekt, unter dem künstlerische Handlungsfelder wie jene von Un-Curating the Archive zusammengefasst werden können, beschreibt Hanne Seitz folgendermaßen: „Das Forschungsanliegen will Wirklichkeit weder graphisch einfangen noch sprachlich beschreiben, weder vorgängige Hypothesen überprüfen noch vorausgehenden Fragen folgen, auch keine Prozesse dokumentieren. Es will mit der Praxis identisch sein und im Bearbeiten, Umgehen, Behandeln von Praxis implizites Wissen aktivieren und neue Kenntnis generieren […] – Forschen in eigener Sache, das im Vollzug des Handelns Auskunft gibt und durchaus auch habitualisierten Einschreibungen auf die Spur kommt.“[2] Ordner für Ordner, Seite für Seite, Dokument für Dokument liegt mit Un-Curating the Archive also eine Institution offen vor den Betrachter_innen – ein Potenzial, das nur darauf wartet, entdeckt, benutzt und ausgeschöpft zu werden, ein Möglichkeitsraum also, den das Künstlerduo zum eigentlichen Protagonisten seines Werks gemacht hat.

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch haben das Archiv im Maßstab 1:1 digitalisiert, gebunden und ausgestellt. Bei dem, was Betrachter_innen mit Un-Curating the Archive als Installation mit Büchern, Tischen, einem Lesedisplay und einer räumlichen Intervention vor sich finden, handelt es sich jedoch nicht mehr um ein Archiv, denn der Arbeitsschritt der simplen aber vollständigen Reproduktion aller Daten hat das Konvolut an Korrespondenzen, Notizen, Einladungskarten, Stücklisten und sonstigen Unterlagen der Camera Austria vom Archiv in eine Bibliothek verwandelt. Denn zieht man eine Trennlinie zwischen Archiv und Bibliothek, so lässt sich der größte Unterschied zwischen diesen beiden Institutionen an ihren Sammlungsgegenständen festmachen: „Die Bibliothek sammelt Werke, das heißt in sich geordnete Artefakte und Datenspeicher, die für ein Gedenken gemacht wurden. Das Archiv hingegen sammelt unprozessierte Objekte, die keineswegs für ein Gedenken gemacht wurden, ‚rohe‘ Daten, ‚unmittelbare‘ Vergangenheit, das Reale.“[3]

Doch während Six/Petritsch die bestehende Ordnung der Materialien des Archivs benutzen, um eine übergeordnete Struktur für ihre Bibliothek zu schaffen, bleibt die materielle Dichte und die Intransparenz des Archivs in Un-Curating the Archive bestehen – eine Setzung, durch welche die Intervention zum künstlerischen Werk wird. In Analogie zur Camera Austria, diesem Hybrid aus Ausstellungsraum und Magazin, ist die Installation schließlich auch als eine Mischform zu begreifen, die sich eindeutiger Zuschreibungen entzieht: Manifestation einer kuratorischen Praxis, in der die Gesten des Auswählens und Zeigens überstilisiert sind; vollständige Datensammlung einer Institution, die sich im reproduktiven Moment der Verdoppelung aufzulösen beginnt; fotografische Arbeit, deren Ziel das Medium des Buchs ist – ein Archiv, das zur Bibliothek geworden ist. Müsste man Un-Curating the Archive trotz aller Mehrdeutigkeit beschlagworten, schnell käme man zum Begriff des Bibliochivs.

[1] Für den vorliegenden Text übersetzt: Sheikh, Simon: Towards The Exhibition As Research, in: O‘Neill, Paul; Mick Wilson (Hg.): „Curating and Research“, London / Amsterdam: Open Editions / de Appel, 2015, 32–46, hier: 40.

[2] Seitz, Hanne: Performative Research, in: Kulturelle Bildung Online, https://www.kubi-online.de/artikel/performative-research (letzter Aufruf: 15.8.2018).

[3] Ebeling, Knut: Wilde Archäologien 2. Begriffe der Materialität der Zeit – von Archiv bis Zerstörung, Berlin: Kadmos, 2016, 21.

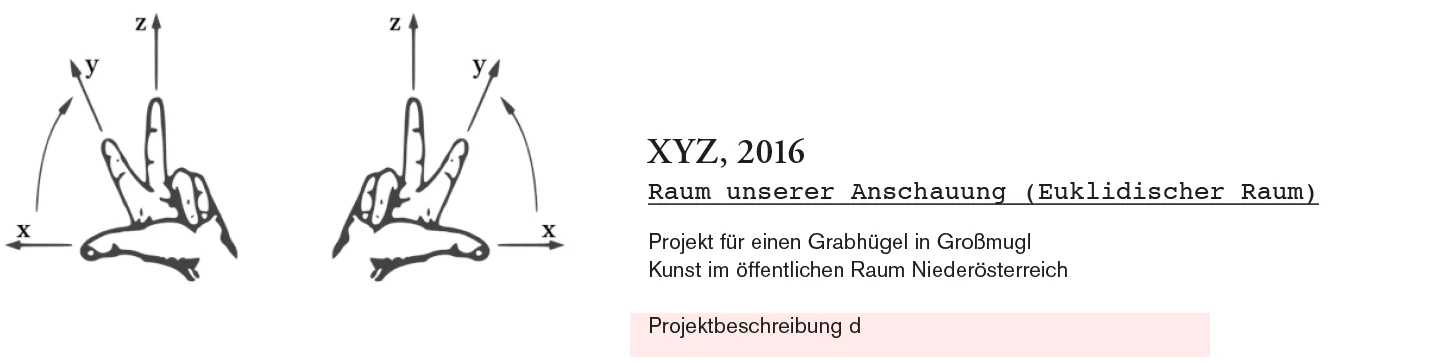

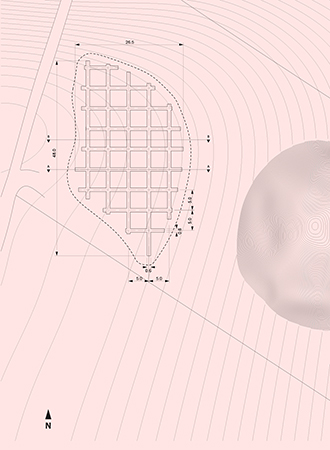

Wege zur Betrachtung und Wahrnehmung

Eine „Wegebene“ wird geschaffen, die den Besuchern ermöglicht einen definierten Standpunkt zum Tumulus einzunehmen und sich dem Hügelgrab gegenüber zu stellen. Es entstehen neue Blickachsen zum Tumulus, zur umliegenden Landschaft und zum Himmel.

Die Ebene erhebt sich aus der Landschaft und wird durch ein Koordinatensystem strukturiert, das nach den Himmelsrichtungen Nord/Ost/Süd/West ausgerichtet ist.

Blick nach Unten - Bodenprospektion

Die 2016 durchgeführte Bodenprospektion enthüllt die vorrömischen Strukturen die sich unter der Erdoberfläche verbergen. Diese Informationen, die sich nicht an der Oberfläche abzeichnen, werden in die Informationsebene des Wegenetzes eingeschrieben und dadurch räumlich nachvollziehbar.

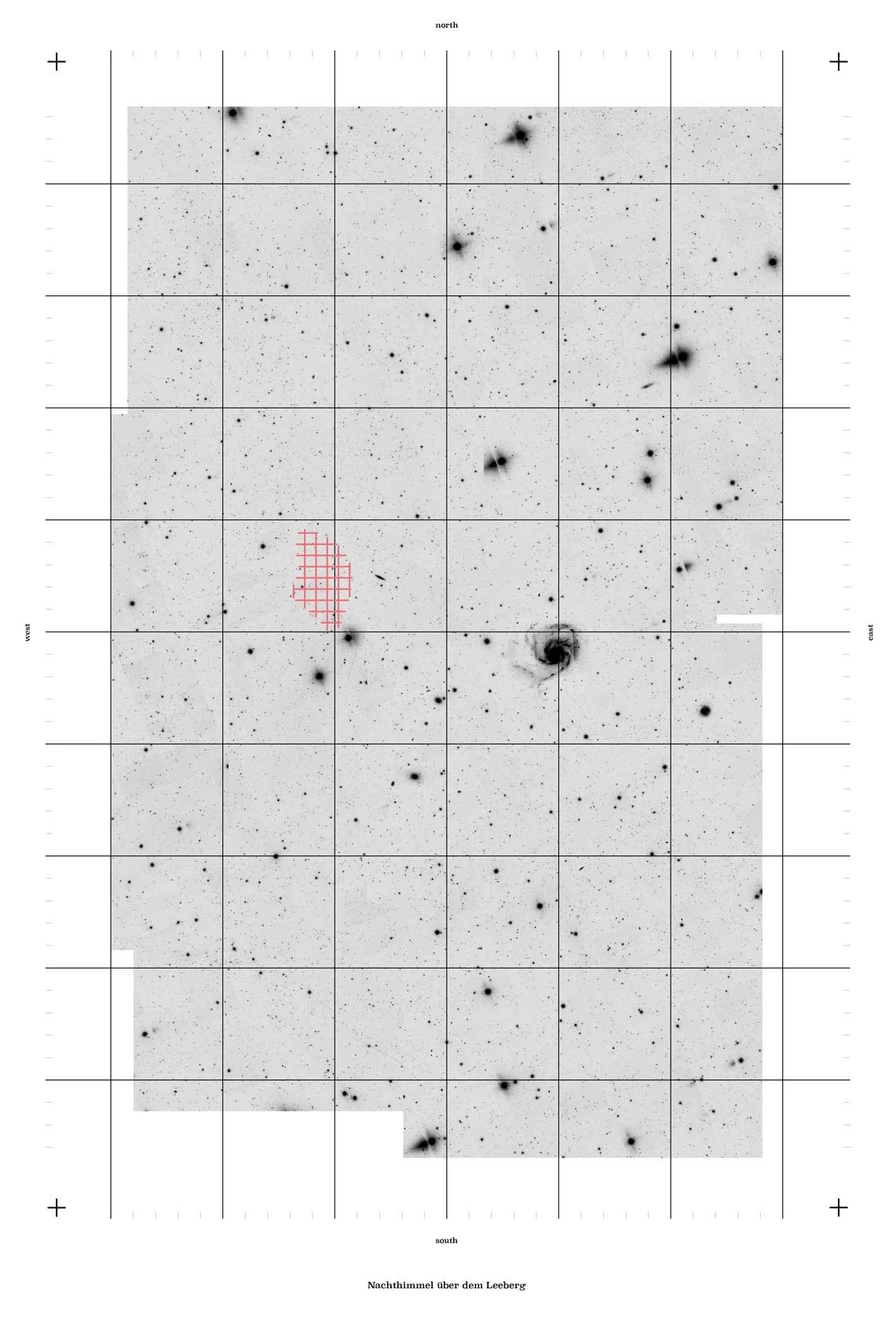

Blick nach Oben - Nachthimmel über dem Leeberg

Als kartographisches Bezugssystem, funktioniert das Netz auch in umgekehrter Richtung:

durch die Ausrichtung nach den Himmelsrichtungen kann auf die Postion von Sternenkonstellationen und die Mondwege Bezug genommen werden. Astronomische Positionen werden direkt mit dem Ort verknüpft.

Das Koordinatensystem ist aus Beton ausgeführt, ca. 60cm breite, begehbare Betonstreifen.

Die dem Tumulus zugewandte Kante, der dabei entstehenden Geländeformation verläuft entlang einer bestehenden Höhenschichtenlinie. Es entstehen Wege und Felder, diese werden für den Besucher zu Informationsebenen. Die Ebenen sind thematisch gegliedert und können begangen und frei miteinander kombiniert werden.

- Blick unter die Oberfläche

- Betrachtung eines Hügelgrabes

- Ortsbegehung / Landschaften

- Blick ins All

„The Monument“, 2015

In their new project, the artists again raise questions of memory and history. Six and Petritsch are shooting a film about Carinthia. Which symbols or monuments are suitable for expressing the lasting impression of human suffering that comes from war and displacement? How is it possible to escape the perpetuation of political propaganda and the fragmentation of remembrance along the lines of the respective ideological groupings? Sometimes it takes a radical gesture. Art has the freedom to make room for a new memorial culture by overwriting and draining of meaning existing forms of commemoration.

camera and editing: Robert Schabus

cooperation: Peter Petritsch & Andreas Krištof

„Das Denkmal“, 2015

Die Frage, welche Denkmäler wir uns heute erträumen und welcher wir bedürfen, ist auch im österreichweiten und internationalen Kontext virulent. Hier ist die zeitgenössische bildende Kunst gefordert. Es kommt ihr in diesem Zusammenhang eine wichtige Aufgabe zu, die von anderen Institutionen, sei es geschichtliche Forschung oder Politik alleine nicht geleistet werden kann. Diese Aufgabe rührt noch von ihrer ursprünglichen Funktion her, Ort der Gemeinschaft zu markieren und zu gestalten.

„Das Denkmal“, ein Projekt des Künstlerduos Six Petritsch, thematisiert Erinnerungskultur in einem spezifischen lokalen Kontext. „Das Denkmal“ ist sowohl Aktion als auch Ausstellung. Die Künstler nehmen ein Element der Geschichte auf, in dem die komplexe Genese der Erinnerungskultur sichtbar wird. Ziel des Projekts ist, durch erzeugen einer Leerstelle möglicherweise eine Korrektur der bestehenden Praxis des Gedenkens anzuregen.

Kamera und Schnitt: Robert Schabus

Mitarbeit: Peter Petritsch & Andreas Krištof

Six screens, six projectors, six cameras