- 2026

- minus20degree, Flachau /P

- 2025

- Transformator, Gedächtnis- & Transformationsraum | spominski & transformacijski prostor, Bad Eisenkappel | Železna Kapla /P

Drugi spomenik / The Other Monument, museum.kärnten, Klagenfurt /V

Paul Albert Leitner`s Photographic World, Camera Austria, Graz /D

2 Tonnen Kalkstein, Kunstraum Ideal, Leipzig (cat.) /G

Nach Anna Lülja Praun, S.I.X., Seewalchen /G

Hinschaun! / Poglejmo!, Kärnten Museum, Klagenfurt /G

Das menschliche und das tierische Wesen, Ursulinenkirche, Linz /E

Suburbia, Architekturzentrum Wien /D

Kardinal König Kunstpreis, Bildraum, Bregenz /G - 2024

- Ich muss mich erstmals sammeln!, HLMD - Hessisches

Landesmuseum Darmstadt /G

Kardinal König Kunstpreis, Lentos, Linz /G

Preise und Talente 2023, Kunstsammlung Oberösterreich, Linz /G

Kulturpreise des Landes Niederösterreich 2024, DOK NÖ Niederösterreichisches Dokumentationszentrum, St.Pölten /G

Neues aus der Sammlung, Kunstsammlung Oberösterreich, Linz /G

Steirische Fotobiennale, Altes Kino Leibnitz /G

Landschaft re_artikulieren, Museum Moderner Kunst Klagenfurt (cat.) /G

Schriftmuseum Pettenbach, Pettenbach /D

Über die Schwelle, Kunst und Kultur der Diözese Linz,

Hallstatt - Kulturhauptstadt Bad Ischl Salzkammergut /G

NHM Biennale Klimatalk#1, Naturhistorisches Museum Wien,

Klima Biennale Vienna /V

Art&Function_Performance, Kunsthaus Mürz, Mürzzuschlag /G

Die Reise der Bilder, Lentos Linz – Kulturhauptstadt Bad Ischl

Salzkammergut (cat.) /G

Broncia Koller-Pinell, Belvedere, Vienna (cat.) /D

Gedenkort Reichenau Innsbruck, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

(competition) /P

Täterätätää, Back with a Bang!, Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Vienna /G

Sudhaus. Kunst mit Salz und Wasser, Kulturhauptstadt Bad Ischl Salzkammergut /G - 2023

- Observations, Collecting Norden, Worlding Northern Art (WONA) and Exploration, Exploitation and Exposition of the Gendered Heritage of the Arctic (XARC), Acadamy of Arts, Tromsø /V

Kyiv Biennale 2023, Vienna /G

Coincidence of Wants, Musa Wien Museum /G

graben/Landschaft/lesen-kopati/Grapo/brati,Bad Eisenkappel/Železna Kapla/G

Wer gedenkt der Partisaninnen und Partisanen? – Kdo se spominja partizank in partizanov?, Museum am Peršmanhof/Muzej Peršmanu, Železna Kapla /G

Labor und Bürogebäude an der Johannes Gutenberg Universität Mainz, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum (Wettbewerb) /P

Display und Ausstellungsraum, BIG ART, BIG, Vienna /D

LBS Holztechnikum Kuchl, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum (competition) /P

Künstler*innenbücher zu Gast: Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch,

Fotohof, Salzburg /E

Shared Space, Versuchsanstalt WUK Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Vienna /E

Edition Camera Austria (Hrsg. Reinhard Braun), Graz /D

@domplatz, Koroška/Kärnten gemeinsam Erinnern / skupno ohranimo spomin, Initiative Domplatz, Universität Klagenfurt /G - 2022

- Das Fest, MAK – Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna /G

Nach 2022 Jahren, Schlossmuseum, Linz /E

Koroška/Kärnten gemeinsam Erinnern / skupno ohranimo spomin, Initiative Domplatz, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum /P

Der Park, St.Agnes, Völkermarkt /G

Lueger Temporär, KÖR, Vienna /E

Inner Boarder, Pavelhaus | Pavlova Hiša, Radkersburg /G

Herbert Bayer, Lentos, Linz /D

Tableaux Vivants/Moving Stills, Architekturforum Zürich /G

Monumental Cares, University of Applied Arts, Vienna /V

XX Y X, Echoraum, Vienna /G

Rethinking Nature, Foto Wien /G - 2021

- Hungry for Time, Academy of Fine Arts Vienna /G

Retrospective Österreichischer Grafikwettbewerb, Taxispalais

Kunsthalle Tirol, Innsbruck /G

Notations, reflections & strategies of display, Contingent Agencies, Vienna /G

Later, gfk-Gesellschaft für Kulturpolitik OÖ, Linz /G

Rethinking Nature, Imago Lisboa, Lisboa /G

Tagung Block Beuys, Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt (cat.) /D

Rethinking Nature, Casino Luxembourg - Forum d'art, Luxembourg /G

A Short History of Camera Traps, Fotograf Gallery, Prague /G

Gemeindezentrum Vöcklamarkt, Art in public space (competition) /P

Forming the Reformed, Academy of Fine Arts, Prague /V - 2020

- Der Angriff der Gegenwart, Universitätsgalerie Heiligenkreuzer Hof, Vienna (cat.) /G

Kärnten Koroška, von A-Ž, Landesgalerie Klagenfurt (cat.) /G

Nach uns die Sintflut, Kunst Haus Vienna (cat.) /G

Die Stadt & Das gute Leben, Camera Austria, Graz /G

Unplugged, Rudolfinum, Prague (cat.) /G

Carinthija, 2020, State Exhibition, Carinthia /G

Sexy Pages, Atelierhaus Hannover /G

Feuerstelle, lower austrian culture, art in public space , Klein-Meiseldorf /P

Fastentuch Vöcklamarkt, Diözesankonservatorat Linz /P

Die Nachbarn, Art in public space, Salzburg (competition) /P

Editionale Wien, University of Applied Arts, Vienna /G

The World to Come, DePaul Art Museum, Chicago (cat.) /G - 2019

- Ozeanische Gefühle, Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt /E

Im Raum die Zeit lesen, mumok - Museum moderner Kunst

Stiftung Ludwig, Vienna /G

Vienna Art Book Fair #1, VABF with University of Applied Arts Vienna /G

Tag des Denkmals - Sea of Tranquility, The Pit, Breitenbrunn /V

Cinema of the Anthropocene, UNC-Wilmington, North Carolina /V

50 Jahre Mondlandung-10 Jahre Salzamt, Salzamt, Linz /G

ticket to the moon, Kunsthalle Krems (cat.) /G

Für die Vögel, lower austrian culture, art in public space /P

The World to Come, UMMA University Michigan Museum of Art (cat.) /G

Lentos-Außen, Linz (competition) /P

Klagenfurter Kunstfilmtage, Klagenfurt /V

Österreichbild, Architekturzentrum Vienna /P

Lassnig-Rainer, Lentos, Linz (cat.) /D - 2018

- Aufbruch ins Ungewisse – Österreich seit 1918,

Haus der Geschichte, Vienna /G

Lost and Found, T.R.A.M., Vienna/Bratislava (cat.) /P

In the case, haaaauch-quer, Klagenfurt /P

Das Denkmal, Museum und Gedenkstätte Peršmanhof, Železna Kapla /V

Rennes Ours, colophon, achevé d'imprimer : le livre d'artiste et le péritexte, Cabinet du Livre d'artiste, Agen, France /G

Project for the preservation of a tumulus, Großmugl, Lower Austria /P

Sommerfrische Reloaded 2018, S.I.X., Seewalchen /G

The World to Come, Harn Museum of Art, Florida (cat.) /G

Yesterday Today Today, Kunstraum Buchberg, Schloss Buchberg (cat.) /G

Garten der Künstler, Minoritenkloster, Tulln (cat.) /G

Post Otto Wagner, MAK – Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna (cat.) /G

Das andere Land, Museum Moderner Kunst Klagenfurt (cat.) /G

1918- Klimt. Moser. Schiele. Gesammelte Schönheiten, Lentos, Linz /D

Auf die Plätze / Na mesta, Künstlerhaus Klagenfurt /G - 2017

- Floor, Wall, Body, Offspace-Night Vienna Art Week, Vienna /V

Grau in Grau – Ästhetisch Politische Praktiken der Erinnerungskultur,

Kunstuniversität Linz /V

Flüchtige Territorien, Kunstraum Niederösterreich, Vienna (cat.) /G

Uncommon Places, Goethe Institut, Hongkong /G

Mapping Terrains, Arccart, Vienna /G

Stretching the Boundaries, Fluca, Plovdiv /G

Kunst am Bau, Bruckner-Universität, Linz (competition) /P

Sterne. Kosmische Kunst, Lentos, Linz (cat.) /G

Un-Curating the Archive, Camera Austria, Graz /E

Unschärfen und weiße Flecken, Künsthaus Mürz (cat.) /G

AHEAD of the Game!, Künstlerhaus Klagenfurt /G - 2016

- Einrichtung, Camera Austria, Graz /D

Psst: there is still place in outer space!, Pavelhaus/Pavlova Hiša,

Radkersburg /G

Am Ende: Architektur, Architekturzentrum Vienna /D

Mahnmal für aktive Gewaltfreiheit, Linz (competition) /P

Herwig Turk Landschaft=Labor, Museum Moderner Kunst

Klagenfurt (cat.) /G

Ein stiller Begleiter, Großmugl /P

Seeing is believing, Museum Angerlehner, Wels (cat.) /G

SUPER J’arrive, Super Wien, Vienna /G - 2015

- Das Denkmal, Institut für Staatswissenschaften, Vienna /V

Filmbau. Schweizer Architektur im bewegten Bild, SAM Schweizerisches

Architekturmuseum, Basel (cat.) /G

Mehr als Zero, Hans Bischoffshausen, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere,

Vienna (cat.) /D

Fronteras En Cuestión II, Centro de Desarollo de las Artes Visuales,

Habana /G

Revers de Tromp, Academy of fine arts Vienna /G

Das Denkmal, Parallel Vienna, Vienna /G

Palm Capsule, Exposition Park, Los Angeles /P

Uncommon Places, Synthesis Gallery of Photography, Sofia /G

Fictitious Tales about the History of Earth, MAK Center, Los Angeles /G

Nicole Six & Paul Petritsch, Das Denkmal, Kunstraum Lakeside,

Klagenfurt /E

Mainzer Ansichten, Kunsthalle Mainz /E

The Visual Paradigm, Camera Austria, Graz /G

Vienna for Art`s Sake, Winter-Palast Belvedere, Vienna (cat.) /G - 2014

- Lichtblicke, Universitätskulturzentrum UNIKUM und section a, Trzic /G

Korrelation, Angewandte Innovation Laboratory, Vienna /G

Wirklichkeit und Konstruktion, Stadtgalerie Klagenfurt (cat.) /G

Die Gegenwart der Moderne, Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig /V

Unframed, Galerie Raum mit Licht und Eikon, Vienna /G

Archives, Re-Assemblances and Surveys, On Austrian Contemporary

Photography, Klovicevi dvori Gallery, Zagreb (cat.) /G

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch, Das Meer der Stille, Landesgalerie Linz (cat.) /E

Fade into You, Kunsthalle Mainz /V

MAK Design Labor, MAK – Österreichisches Museum für angewandte

Kunst, Vienna /G

Places of Transition, Freiraum – MuseumsQuartier Wien (cat.) /D - 2013

- Suicide Narcissus, The Renaissance Society, Chicago /G

Gefährdung, Entzug und grundloses Aushalten, Transmediale Kunst -

Universität für angewandte Kunst, Vienna /V

Vienna for Art`s Sake, Benetton Collection, Treviso (cat.) /G

Kunstgastgeber – Rennbahnweg 27, KÖR Kunst im öffentlichen Raum,

Vienna (Kat.) /P

Denkmal für die Verfolgten der NS-Miltärjustiz, Ballhausplatz 1010 Vienna /P

Nebelland hab ich gesehen, Museum Moderner Kunst Klagenfurt (cat.) /G

Is it really you, Kunstsammlung Oberösterreich, Linz /G

Praxis der Liebe, Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg /D

Das Bauhaus in Kalkutta, Bauhaus Dessau /D

Wolken, Welt des Flüchtigen, Leopold Museum, Vienna (cat.) /G

Schuss / Gegenschuss, in: Camera Austria, Nr. 121 /P - 2012

- Art is Concrete, Camera Austria, Graz /D

Sowjetmoderne, Architekturzentrum Vienna /D

Aus, Schluss Basta oder Wir sind total am Ende, Schauspielhaus Graz /V

Keine Zeit, erschöpftes Selbst / entgrenzetes Können, 21er Haus,

Vienna (cat.) /G

Space Affairs, Musa, Vienna /G

Aussicht kann durch Ladung verstellt sein, Kunstverein Medienturm,

Graz (cat.) /E - 2011

- Im täglichen Wahnsinn den Zauber finden!, Kunstraum Goethestrasse

xtd, Linz /G

Schall und Rauch, die Vertikale und der freie Fall, TransArts - Universität

für angewandte Kunst, Vienna /V

If a tree falls in the forest, and nobody hears it, does it make a sound?,

Galerie Lisa Ruyter, Vienna /G

Das Ding an sich, Mariendom, Linz /P

Raum für 17 Minuten 6’23’’, Galerie im Taxispalais, Innsbruck (cat.) /E

Prima Interventionen, Atelierhaus Salzamt, Linz /G

Proposals for Venice, Landesgalerie Linz (cat.) /G - 2010

- Körper Codes, Museum der Moderne Salzburg /G

Der Aufstand der Zeichen, k48, Vienna, Intervention im öffentlichen Raum /P

Heimat/Domovina, Museum Moderner Kunst Klagenfurt (cat.) /G

Triennale Linz 1.0, Linz (cat.) /G

Blind Date, Kunstverein Hannover /E

Atlas, Secession, Vienna (cat.) /E

Upon Arrival, Malta Contemporary Art, Malta (cat.) /G - 2009

- Österreichischer Grafikwettbewerb (31), Galerie im Taxispalais,

Innsbruck (cat.) /G

Mahnmal für die Zwangsarbeitslager St. Pölten - Viehofen,

in Zusammenarbeit mit Jeanette Pacher (nicht realisiert) /P

Das menschliche und das tierische Wesen, Ursulinenkirche, Linz /E

Reading the City, ev+a 2009, Limerick (cat.) /G

Spotlight, Museum der Moderne, Salzburg /G - 2008

- Undiszipliniert, Das Phänomen Raum in Kunst, Architektur und Design, Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Vienna (cat.) /G

Peter Zumthor, Bauten und Projekte 1986–2007 mit einer Filminstallation von Nicole Six & Paul Petritsch, Experimentadesign, Lissabon /P

zu Gironcoli, Gironcoli Museum, Herberstein /G

K08, Emanzipation und Konfrontation, Künstlerhaus Klagenfurt (cat.) /G

Was ist ein Platz? Was ist ein Cy-BORG-Platz?, Temporäre Kunst im Stadtraum, Wiener Neustadt /P

unterwegs sein, Kunstraum Düsseldorf (cat.) /G

Bildpolitiken, Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg /D

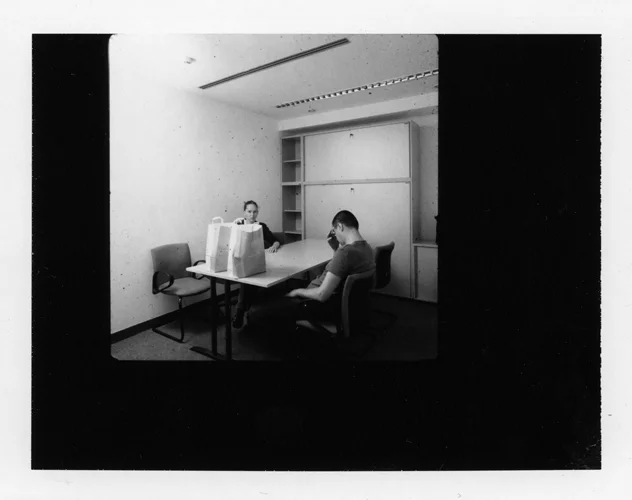

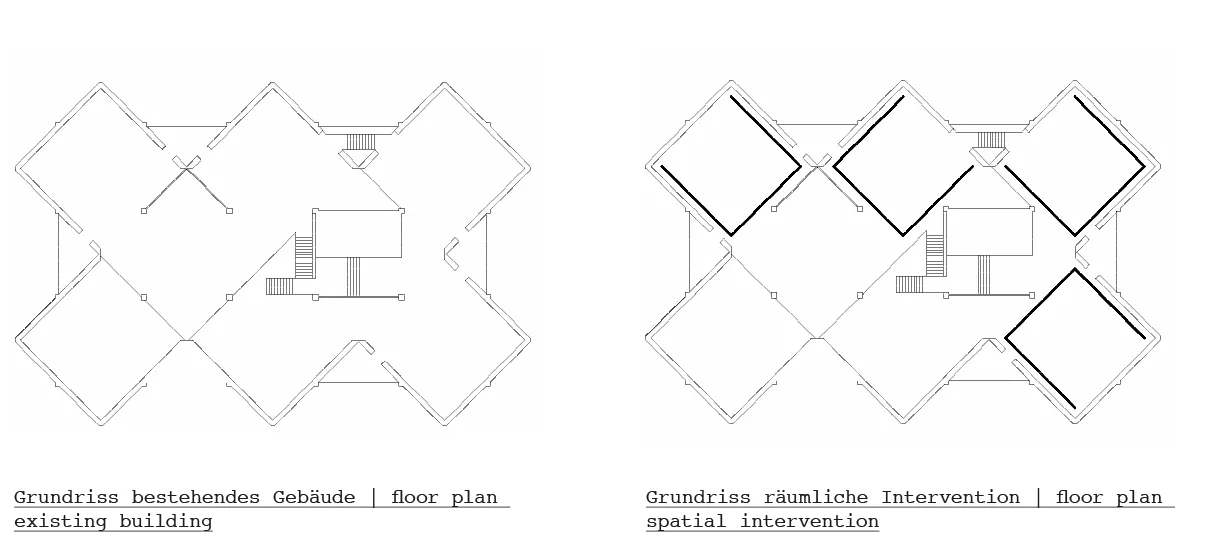

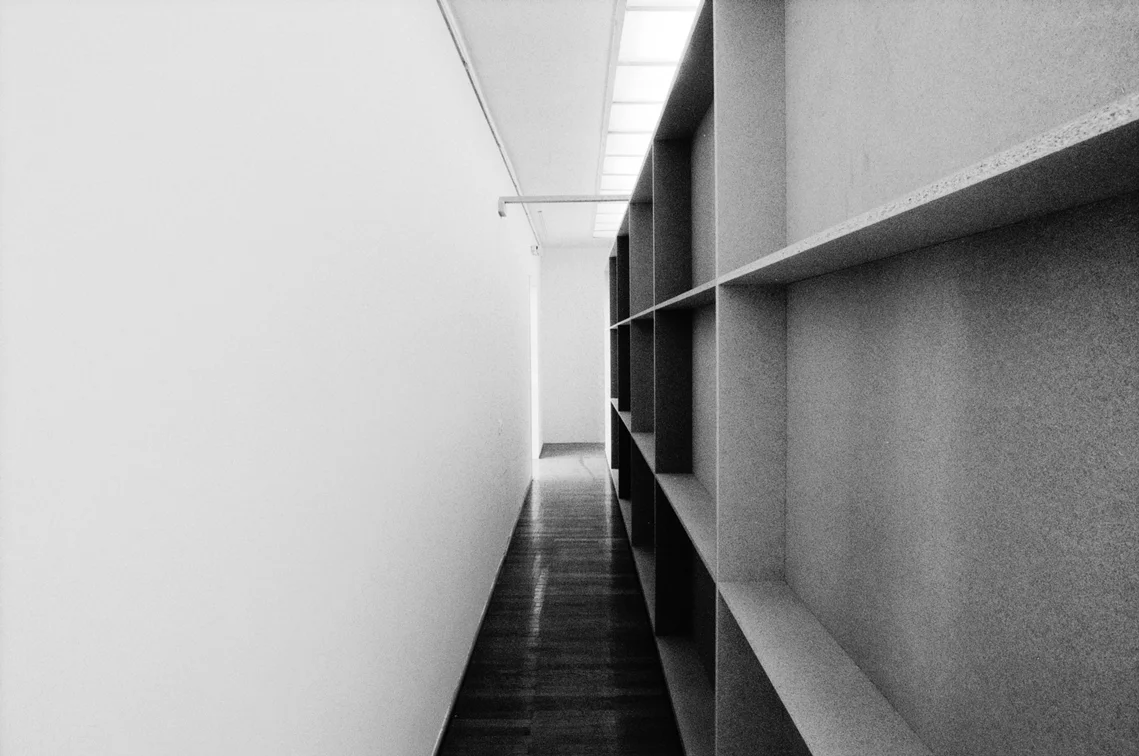

Kontakt...aus der Sammlung der Erste Bank-Gruppe, Institut

of Contemporary Art, Dunaújváros /D

zoom and scale, Akademie der bildenden Künste, Vienna /G - 2007

- Max Ernst und die Welt im Buch, Museum der Moderne, Salzburg /G

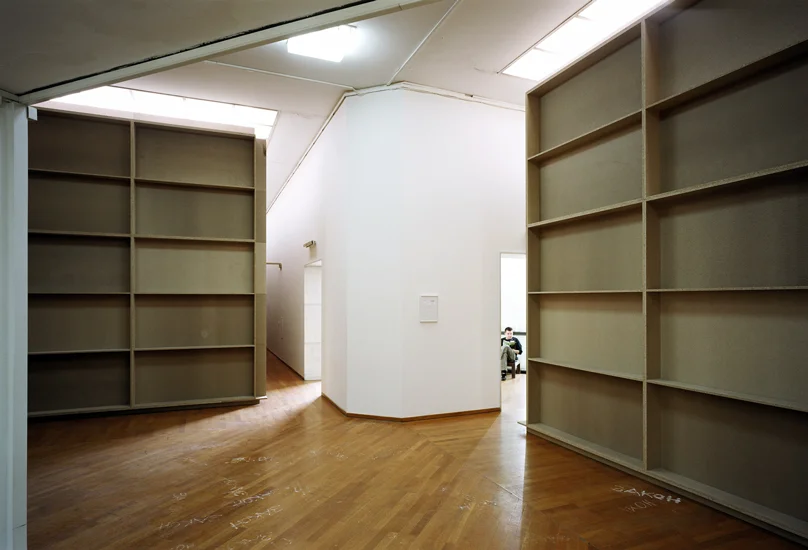

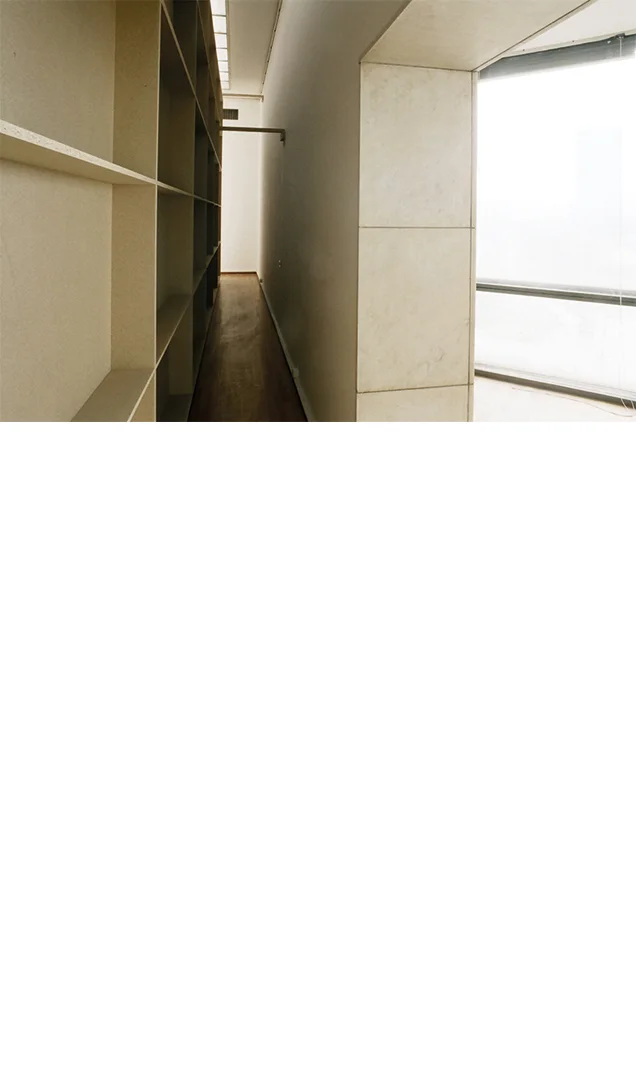

Peter Zumthor, Bauten und Projekte 1986–2007 mit einer Filminstallation von Nicole Six & Paul Petritsch, KUB Kunsthaus Bregenz /P

Temporally, The Israeli Center for Digital Art, Holon /G

Margherita Spiluttini. Atlas Austria, Architekturzentrum Vienna /D

Kunstverein Baden, Kunstverein Baden /G

Blickwechsel Nr.3, MMKK, Klagenfurt (cat.) /G

I`m too tired to tell you, Agentur, Amsterdam /E

Film ab, Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst, BIG, Vienna /P

Kontakt Belgrad...aus der Sammlung der Erste Bank-Gruppe, Museum Moderner Kunst, Belgrad /D - 2006

- Longitude / Latitude, haaaauch, Klagenfurt /E

Nicole Six / Paul Petritsch, Gesellschaft für aktuelle Kunst, Bremen /E

First the artist defines meaning, Camera Austria, Graz /G

Société des nations, Circuit, Lausanne /G

How and Wow, Experimentelle Gestaltung Kunstuniversität Linz, Linz /V

Kontakt...aus der Sammlung der Erste Bank-Gruppe, Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig, Vienna /D

Margherita Spiluttini. Atlas Austria, Architekturzentrum Wien mit Arco, Madrid /D - 2005

- Tu Felix Austria…Wild at Heart, KUB Kunsthaus Bregenz (cat.) /G

Home Stories, Architekturzentrum Wien mit Austrian Cultural Forum,

New York /D

Das Spannende ist doch die Organisation von Materie, Area 53, Vienna /G

Wisdom of Nature, Nagoya City Art Museum, Nagoya (cat.) /G

Das Neue 2, Atelier im Augarten, Zentrum für zeitgenössische Kunst der Österreichischen Galerie Belvedere, Vienna (cat.) /G

Großmugl, Wettbewerb Kunst im öffentlichen Raum, Großmugl

(unrealized) /P

Museums-Empfangsbereich, Frac Lorraine, Metz, Frankreich /P

Slices of Life, blueprints of the self in painting, Austrian Cultural Forum,

New York /D - 2004

- Open Studio, ISCP, New York /G

Transgressing-Systems, Ausstellen zu Bauen und Kunst, Innsbruck /G

1.33.33, Area 53, Wien /G

Permanent Produktiv, Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Vienna /G

White Spirit in Public Spaces, F.R.A.C. de Lorrain, Metz /G

The Austrian Phenomenon / Konzepte Experimente Wien Graz 1958-1973, Architekturzentrum Vienna /D - 2003

- Fata Morgana, Wettbewerb Silos Graz-West, Kulturhauptstadt Graz 2003

in collaboration with Jeanette Pacher (unrealized) /P

Flutlichtmast, Wettbewerb Kunst im öffentlichen Raum in Rohrendorf

in collaboration with Hans Schabus (unrealized) /P

Trauer, Atelier im Augarten, Zentrum für zeitgenössische Kunst der Österreichischen Galerie Belvedere, Vienna (cat.) /G

America, bgf_plattform, Berlin /G

Extended Architecture, Tanzwerkstatt Europa, Neues Theater, München /G

just build it! Die Bauten des Rural Studio, Architekturzentrum Vienna /D

site-seeing: disneyfizierung der städte, Künstlerhaus Vienna /D - 2002

- artists´choice, CAT Contemporary Art Tower – MAK

Gegenwartskunstdepot, Vienna /E

space off, supersaat, Vienna /G - 2001

- moving out, Universität für angewandte Kunst, Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Vienna /D

/E Solo Exhibition

/G Group Exhibition

/P Projects: Interventions, Public Space, Competition or realized Projects

/D Display: Exhibition, Catalogs

/V Lecture and Screenings, Presentations

- 2026

- minus20degree, Flachau /P

- 2025

- Transformator, Gedächtnis- & Transformationsraum | spominski & transformacijski prostor, Bad Eisenkappel | Železna Kapla /P

Drugi spomenik / Das andere Denkmal, museum.kärnten, Klagenfurt /V

Paul Albert Leitner`s Photographic World, Camera Austria, Graz /D

2 Tonnen Kalkstein, Kunstraum Ideal, Leipzig (Katalog) /G

Nach Anna Lülja Praun, S.I.X., Seewalchen /G

Hinschaun! / Poglejmo!, Kärnten Museum, Klagenfurt /G

Das menschliche und das tierische Wesen, Ursulinenkirche, Linz /E

Suburbia, Architekturzentrum Wien /D

Kardinal König Kunstpreis, Bildraum, Bregenz /G - 2024

- Ich muss mich erstmals sammeln!, HLMD - Hessisches

Landesmuseum Darmstadt /G

Kardinal König Kunstpreis, Lentos, Linz /G

Preise und Talente 2023, Kunstsammlung Oberösterreich, Linz /G

Kulturpreise des Landes Niederösterreich 2024, DOK NÖ Niederösterreichisches Dokumentationszentrum, St.Pölten /G

Neues aus der Sammlung, Kunstsammlung Oberösterreich, Linz /G

Steirische Fotobiennale, Altes Kino Leibnitz /G

Landschaft re_artikulieren, Museum Moderner Kunst Klagenfurt (Katalog) /G

Schriftmuseum Pettenbach, Pettenbach /D

Über die Schwelle, Kunst und Kultur der Diözese Linz,

Hallstatt - Kulturhauptstadt Bad Ischl Salzkammergut /G

NHM Biennale Klimatalk#1, Naturhistorisches Museum Wien,

Klima Biennale Wien /V

Art&Function_Performance, Kunsthaus Mürz, Mürzzuschlag /G

Die Reise der Bilder, Lentos – Kulturhauptstadt Bad Ischl

Salzkammergut (Katalog) /G

Broncia Koller-Pinell, Belvedere, Wien (Katalog) /D

Gedenkort Reichenau Innsbruck, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

(Wettbewerb) /P

Täterätätää, Back with a Bang!, Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Wien /G

Sudhaus. Kunst mit Salz und Wasser, Kulturhauptstadt Bad Ischl Salzkammergut /G - 2023

- Observations, Collecting Norden, Worlding Northern Art (WONA) and Exploration, Exploitation and Exposition of the Gendered Heritage of the Arctic (XARC), Acadamy of Arts, Tromsø /V

Kyiv Biennale 2023, Wien /G

Coincidence of Wants, Musa Wien Museum /G

graben/Landschaft/lesen-kopati/Grapo/brati,Bad Eisenkappel/Železna Kapla/G

Wer gedenkt der Partisaninnen und Partisanen? – Kdo se spominja partizank in partizanov?, Museum am Peršmanhof/Muzej Peršmanu, Železna Kapla /G

Labor und Bürogebäude an der Johannes Gutenberg Universität Mainz, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum (Wettbewerb) /P

Display und Ausstellungsraum, BIG ART, BIG, Wien /D

LBS Holztechnikum Kuchl, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum (Wettbewerb) /P

Künstler*innenbücher zu Gast: Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch,

Fotohof, Salzburg /E

Shared Space, Versuchsanstalt WUK Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Wien /E

Edition Camera Austria (Hrsg. Reinhard Braun), Graz /D

@domplatz, Koroška/Kärnten gemeinsam Erinnern / skupno ohranimo spomin, Initiative Domplatz, Universität Klagenfurt /G - 2022

- Das Fest, MAK – Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Wien /G

Nach 2022 Jahren, Schlossmuseum, Linz /E

Koroška/Kärnten gemeinsam Erinnern / skupno ohranimo spomin, Initiative Domplatz, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum /P

Der Park, St.Agnes, Völkermarkt /G

Lueger Temporär, KÖR, Wien /E

Inner Boarder, Pavelhaus | Pavlova Hiša, Radkersburg /G

Herbert Bayer, Lentos, Linz /D

Tableaux Vivants/Moving Stills, Architekturforum Zürich /G

Monumental Cares, Universität für angewandte Kunst, Wien /V

XX Y X, Echoraum, Wien /G

Rethinking Nature, Foto Wien /G - 2021

- Hungry for Time, Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien /G

Retrospective Österreichischer Grafikwettbewerb, Taxispalais

Kunsthalle Tirol, Innsbruck /G

Notations, reflections & strategies of display, Contingent Agencies, Wien /G

Later, gfk-Gesellschaft für Kulturpolitik OÖ, Linz /G

Rethinking Nature, Imago Lisboa, Lissabon /G

Tagung Block Beuys, Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt (Kat.) /D

Rethinking Nature, Casino Luxembourg - Forum d'art, Luxembourg /G

A Short History of Camera Traps, Fotograf Gallery, Prag /G

Gemeindezentrum Vöcklamarkt, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

(Wettbewerb) /P

Forming the Reformed, Akademie der Bildenden Künste Prag /V - 2020

- Der Angriff der Gegenwart, Universitätsgalerie Heiligenkreuzer Hof, Wien (Kat.) /G

Kärnten Koroška, von A-Ž, Landesgalerie Klagenfurt (Kat.) /G

Nach uns die Sintflut, Kunst Haus Wien (Kat.) /G

Die Stadt & Das gute Leben, Camera Austria, Graz /G

Unplugged, Rudolfinum, Prag (Kat.) /G

Carinthija, 2020, Landesausstellung, Kärnten /G

Sexy Pages, Atelierhaus Hannover /G

Feuerstelle, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum Niederösterreich, Klein-Meiseldorf /P

Fastentuch Vöcklamarkt, Diözesankonservatorat Linz /P

Die Nachbarn, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum Salzburg (Wettbewerb) /P

Editionale Wien, Universität für angewandte Kunst, Wien /G

The World to Come, DePaul Art Museum, Chicago (Kat.) /G - 2019

- Ozeanische Gefühle, Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt /E

Im Raum die Zeit lesen, Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig, Wien /G

Vienna Art Book Fair #1, VABF+Universität für angewandte Kunst Wien /G

Tag des Denkmals - Sea of Tranquility, The Pit, Breitenbrunn /V

Cinema of the Anthropocene, UNC-Wilmington, North Carolina /V

50 Jahre Mondlandung-10 Jahre Salzamt, Salzamt, Linz /G

ticket to the moon, Kunsthalle Krems (Kat.) /G

Für die Vögel, Kunst im öffentlichen Raum Niederösterreich /P

The World to Come, UMMA University Michigan Museum of Art (Kat.) /G

Lentos-Außen, Linz (Wettbewerb) /P

Klagenfurter Kunstfilmtage, Klagenfurt /V

Österreichbild, Architekturzentrum Wien /P

Lassnig-Rainer, Lentos, Linz (Kat.) /D - 2018

- Aufbruch ins Ungewisse – Österreich seit 1918,

Haus der Geschichte, Wien /G

Lost and Found, T.R.A.M., Wien/Bratislava (Kat.) /P

In the case, haaaauch-quer, Klagenfurt /P

Das Denkmal, Museum und Gedenkstätte Peršmanhof, Železna Kapla /V

Rennes Ours, colophon, achevé d'imprimer : le livre d'artiste et le péritexte, Cabinet du Livre d'artiste, Agen, Frankreich /G

Projekt zum Schutz eines Hügelgrabs, Großmugl, Niederösterreich /P

Sommerfrische Reloaded 2018, S.I.X., Seewalchen /G

The World to Come, Harn Museum of Art, Florida (Kat.) /G

Yesterday Today Today, Kunstraum Buchberg, Schloss Buchberg (Kat.) /G

Garten der Künstler, Minoritenkloster, Tulln (Kat.) /G

Post Otto Wagner, MAK – Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst, Wien (Kat.) /G

Das andere Land, Museum Moderner Kunst Klagenfurt (Kat.) /G

1918- Klimt. Moser. Schiele. Gesammelte Schönheiten, Lentos, Linz /D

Auf die Plätze / Na mesta, Künstlerhaus Klagenfurt /G - 2017

- Floor, Wall, Body, Offspace-Night Vienna Art Week, Wien /V

Grau in Grau – Ästhetisch Politische Praktiken der Erinnerungskultur,

Kunstuniversität Linz /V

Flüchtige Territorien, Kunstraum Niederösterreich, Wien (Kat.) /G

Uncommon Places, Goethe Institut, Hongkong /G

Mapping Terrains, Arccart, Wien /G

Stretching the Boundaries, Fluca, Plovdiv /G

Kunst am Bau, Bruckner-Universität, Linz (Wettbewerb) /P

Sterne. Kosmische Kunst, Lentos, Linz (Kat.) /G

Un-Curating the Archive, Camera Austria, Graz /E

Unschärfen und weiße Flecken, Künsthaus Mürz (Kat.) /G

AHEAD of the Game!, Künstlerhaus Klagenfurt /G - 2016

- Einrichtung,, Camera Austria, Graz /D

Psst: there is still place in outer space!, Pavelhaus/Pavlova Hiša,

Radkersburg /G

Am Ende: Architektur, Architekturzentrum Wien /D

Mahnmal für aktive Gewaltfreiheit, Linz (Wettbewerb) /P

Herwig Turk Landschaft=Labor, Museum Moderner Kunst

Klagenfurt (Kat.) /G

Ein stiller Begleiter, Großmugl /P

Seeing is believing, Museum Angerlehner, Wels (Kat.) /G

SUPER J’arrive, Super Wien /G - 2015

- Das Denkmal, Institut für Staatswissenschaften, Wien /V

Filmbau. Schweizer Architektur im bewegten Bild, SAM Schweizerisches

Architekturmuseum, Basel (Kat.) /G

Mehr als Zero, Hans Bischoffshausen, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere,

Wien (Kat.) /D

Fronteras En Cuestión II, Centro de Desarollo de las Artes Visuales,

Habana /G

Revers de Tromp, Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien /G

Das Denkmal, Parallel Vienna, Wien /G

Palm Capsule, Exposition Park, Los Angeles /P

Uncommon Places, Synthesis Gallery of Photography, Sofia /G

Fictitious Tales about the History of Earth, MAK Center, Los Angeles /G

Nicole Six & Paul Petritsch, Das Denkmal, Kunstraum Lakeside,

Klagenfurt /E

Mainzer Ansichten, Kunsthalle Mainz /E

The Visual Paradigm, Camera Austria, Graz /G

Vienna for Art`s Sake, Winter-Palast Belvedere, Wien (Kat.) /G - 2014

- Lichtblicke, Universitätskulturzentrum UNIKUM und section a, Trzic /G

Korrelation, Angewandte Innovation Laboratory, Wien /G

Wirklichkeit und Konstruktion, Stadtgalerie Klagenfurt (Kat.) /G

Die Gegenwart der Moderne, Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig /V

Unframed, Galerie Raum mit Licht und Eikon, Wien /G

Archives, Re-Assemblances and Surveys, On Austrian Contemporary

Photography, Klovicevi dvori Gallery, Zagreb (Kat.) /G

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch, Das Meer der Stille, Landesgalerie Linz (Kat.) /E

Fade into You, Kunsthalle Mainz /V

MAK Design Labor, MAK – Österreichisches Museum für angewandte

Kunst, Wien /G

Places of Transition, Freiraum – MuseumsQuartier Wien (Kat.) /D - 2013

- Suicide Narcissus, The Renaissance Society, Chicago /G

Gefährdung, Entzug und grundloses Aushalten, Transmediale Kunst -

Universität für angewandte Kunst, Wien /V

Vienna for Art`s Sake, Benetton Collection, Treviso (Kat.) /G

Kunstgastgeber – Rennbahnweg 27, KÖR Kunst im öffentlichen Raum,

Wien (Kat.) /P

Denkmal für die Verfolgten der NS-Miltärjustiz, Ballhausplatz 1010 Wien /P

Nebelland hab ich gesehen, Museum Moderner Kunst Klagenfurt (Kat.) /G

Is it really you, Kunstsammlung Oberösterreich, Linz /G

Praxis der Liebe, Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg /D

Das Bauhaus in Kalkutta, Bauhaus Dessau /D

Wolken, Welt des Flüchtigen, Leopold Museum, Wien (Kat.) /G

Schuss / Gegenschuss, in: Camera Austria, Nr. 121 /P - 2012

- Art is Concrete, Camera Austria, Graz /D

Sowjetmoderne, Architekturzentrum Wien /D

Aus, Schluss Basta oder Wir sind total am Ende, Schauspielhaus Graz /V

Keine Zeit, erschöpftes Selbst / entgrenzetes Können, 21er Haus,

Wien (Kat.) /G

Space Affairs, Musa, Wien /G

Aussicht kann durch Ladung verstellt sein, Kunstverein Medienturm,

Graz (Kat.) /E - 2011

- Im täglichen Wahnsinn den Zauber finden!, Kunstraum Goethestrasse

xtd, Linz /G

Schall und Rauch, die Vertikale und der freie Fall, TransArts - Universität

für angewandte Kunst, Wien /V

If a tree falls in the forest, and nobody hears it, does it make a sound?,

Galerie Lisa Ruyter, Wien /G

Das Ding an sich, Mariendom, Linz /P

Raum für 17 Minuten 6’23’’, Galerie im Taxispalais, Innsbruck (Kat.) /E

Prima Interventionen, Atelierhaus Salzamt, Linz /G

Proposals for Venice, Landesgalerie Linz (Kat.) /G - 2010

- Körper Codes, Museum der Moderne Salzburg /G

Der Aufstand der Zeichen, k48, Wien, Intervention im öffentlichen Raum /P

Heimat/Domovina, Museum Moderner Kunst Klagenfurt (Kat.) /G

Triennale Linz 1.0, Linz (Kat.) /G

Blind Date, Kunstverein Hannover /E

Atlas, Secession, Wien (Kat.) /E

Upon Arrival, Malta Contemporary Art, Malta (Kat.) /G - 2009

- Österreichischer Grafikwettbewerb (31) , Galerie im Taxispalais,

Innsbruck (Kat.) /G

Mahnmal für die Zwangsarbeitslager St. Pölten - Viehofen,

in Zusammenarbeit mit Jeanette Pacher (nicht realisiert) /P

Das menschliche und das tierische Wesen, Ursulinenkirche, Linz /E

Reading the City, ev+a 2009, Limerick (Kat.) /G

Spotlight, Museum der Moderne, Salzburg /G - 2008

- Undiszipliniert, Das Phänomen Raum in Kunst, Architektur und Design, Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Wien (Kat.) /G

Peter Zumthor, Bauten und Projekte 1986–2007 mit einer Filminstallation von Nicole Six & Paul Petritsch, Experimentadesign, Lissabon /P

zu Gironcoli, Gironcoli Museum, Herberstein /G

K08, Emanzipation und Konfrontation, Künstlerhaus Klagenfurt (Kat.) /G

Was ist ein Platz? Was ist ein Cy-BORG-Platz?, Temporäre Kunst im Stadtraum, Wiener Neustadt /P

unterwegs sein, Kunstraum Düsseldorf (Kat.) /G

Bildpolitiken, Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg /D

Kontakt...aus der Sammlung der Erste Bank-Gruppe, Institut

of Contemporary Art, Dunaújváros (Display) /D

zoom and scale, Akademie der bildenden Künste, Wien /G - 2007

- Max Ernst und die Welt im Buch, Museum der Moderne, Salzburg /G

Peter Zumthor, Bauten und Projekte 1986–2007 mit einer Filminstallation von Nicole Six & Paul Petritsch, KUB Kunsthaus Bregenz /P

Temporally, The Israeli Center for Digital Art, Holon /G

Margherita Spiluttini. Atlas Austria, Architekturzentrum Wien /D

Kunstverein Baden, Kunstverein Baden /G

Blickwechsel Nr.3, MMKK, Klagenfurt (Kat.) /G

I`m too tired to tell you, Agentur, Amsterdam /E

Film ab, Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst, BIG, Wien /P

Kontakt Belgrad...aus der Sammlung der Erste Bank-Gruppe, Museum Moderner Kunst, Belgrad /D - 2006

- Longitude / Latitude, haaaauch, Klagenfurt /E

Nicole Six / Paul Petritsch, Gesellschaft für aktuelle Kunst, Bremen /E

First the artist defines meaning, Camera Austria, Graz /G

Société des nations, Circuit, Lausanne /G

How and Wow, Experimentelle Gestaltung Kunstuniversität Linz, Linz /V

Kontakt...aus der Sammlung der Erste Bank-Gruppe, Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig, Wien /D

Margherita Spiluttini. Atlas Austria, Architekturzentrum Wien mit Arco, Madrid /D - 2005

- Tu Felix Austria…Wild at Heart, KUB Kunsthaus Bregenz (Kat.) /G

Home Stories, Architekturzentrum Wien mit Austrian Cultural Forum,

New York /D

Das Spannende ist doch die Organisation von Materie, Area 53, Wien /G

Wisdom of Nature, Nagoya City Art Museum, Nagoya (Kat.) /G

Das Neue 2, Atelier im Augarten, Zentrum für zeitgenössische Kunst der Österreichischen Galerie Belvedere, Wien (Kat.) /G

Großmugl, Wettbewerb Kunst im öffentlichen Raum, Großmugl

(nicht realisiert) /P

Museums-Empfangsbereich, Frac Lorraine, Metz, Frankreich /P

Slices of Life, blueprints of the self in painting, Austrian Cultural Forum,

New York /D - 2004

- Open Studio, ISCP, New York /G

Transgressing-Systems, Ausstellen zu Bauen und Kunst, Innsbruck /G

1.33.33, Area 53, Wien /G

Permanent Produktiv, Kunsthalle Exnergasse, Wien /G

White Spirit in Public Spaces, F.R.A.C. de Lorrain, Metz /G

The Austrian Phenomenon / Konzepte Experimente Wien Graz 1958-1973, Architekturzentrum Wien /D - 2003

- Fata Morgana, Wettbewerb Silos Graz-West, Kulturhauptstadt Graz 2003

in Zusammenarbeit mit Jeanette Pacher (nicht realisiert) /P

Flutlichtmast, Wettbewerb Kunst im öffentlichen Raum in Rohrendorf

in Zusammenarbeit mit Hans Schabus (nicht realisiert) /P

Trauer, Atelier im Augarten, Zentrum für zeitgenössische Kunst der Österreichischen Galerie Belvedere, Wien (Kat.) /G

America, bgf_plattform, Berlin /G

Extended Architecture, Tanzwerkstatt Europa, Neues Theater, München /G

just build it! Die Bauten des Rural Studio, Architekturzentrum Wien /D

site-seeing: disneyfizierung der städte, Künstlerhaus Wien /D - 2002

- artists´choice, CAT Contemporary Art Tower – MAK

Gegenwartskunstdepot, Wien /E

space off, supersaat, Wien /G - 2001

- moving out, Universität für angewandte Kunst, Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien /D

/E Einzelausstellungen

/G Gruppenausstellungen

/P Projekte: Intervention, öffentlicher Raum, Wettbewerbe oder realisiert Projekte

/D Display: Ausstellungen, Katalog

/V Vorträge u. Screening, Präsentation

FILMS

- 2025

- Drugi spomenik / Das andere Denkmal

Video with sound

one-channel projection

32 min 22 sec, colour - 2024

- Seemeile (Sumbu und Pekel)

Video with sound

one-channel projection

20 min 49 sec, colour

Die Reise der Bilder

Video with sound

eight-channel projection

24 min 24 sec - 33min 23 sec, colour - 2023

- Lueger Temporär

Video with sound

one-channel projection

22 min 11 sec, colour

05.01.2023 (Pečnikov travnik/Pečnik-Wiese)

Video with sound

four-channel projection

1h 50min, colour - 2021

- Pilot

(Dialogisch den Horizont expandieren - von Klagenfurt nach Klagenfurt)

Video with sound

one-channel projection

11 min 08 sec, colour

Roxy, 27.05.2021 (Block Beuys)

Video with sound

one-channel projection

8 min 12 sec, colour - 2020

- Parallel Worlds

20.03.2020 / 01.04.2020 / 20.04.2020

Video with sound

three-channel projection

23 min 12sec, colour - 2017

- Ohne Titel (Albaner Hafen)

Video with sound

three-channel projection

51 min, colour - 2015

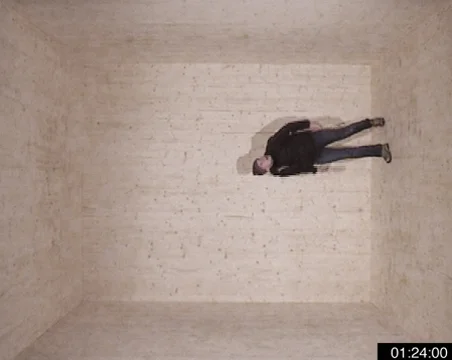

- Das Denkmal

Video with sound

two-channel projection

130 min, colour - 2014

- Raum für 5’16’’

Video with sound

two-channel projection

5 min 16 sec, colour

Das Meer der Stille

Video with sound on DVD

3 min 34 sec, colour - 2011

- Raum für 17 Minuten 6’23’’

Video with sound

two-channel projection

6 min 23 sec, colour - 2009

- Das menschliche und das tierische Wesen

Video with sound

five-channel projection

19 min, colour - 2007

- Ohne Titel, twelve buildings by Peter Zumthor

Video with sound

six-channel projection

480 min, colour

Nebel

Video with sound on DVD

30 min, colour - 2005

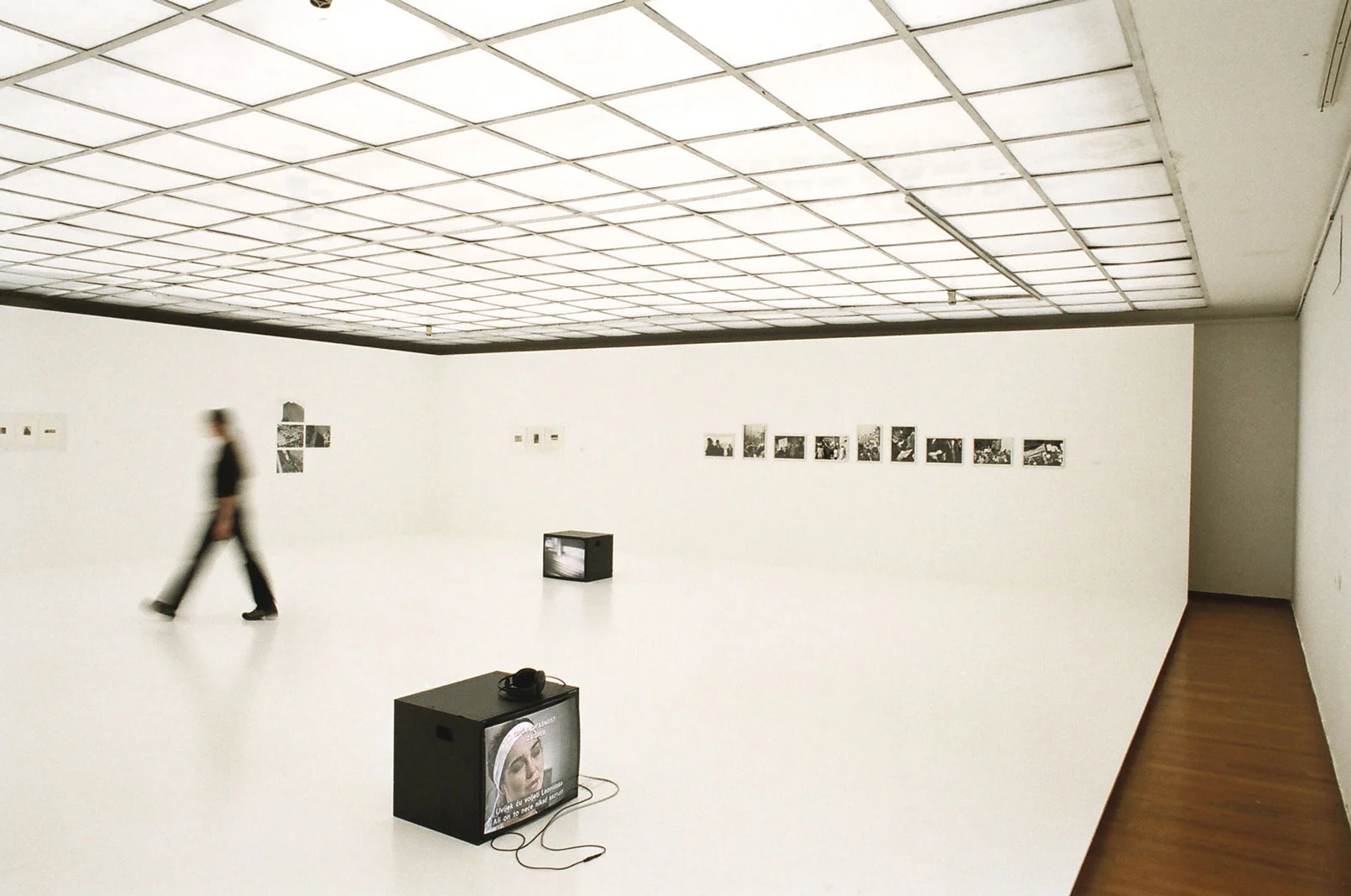

- Ohne Titel, Kunsthaus Bregenz

Video with sound on DVD

six-channel projection

72 h, colour

I’m too tired to tell you

Video on DVD

17 min, colour, silent - 2004

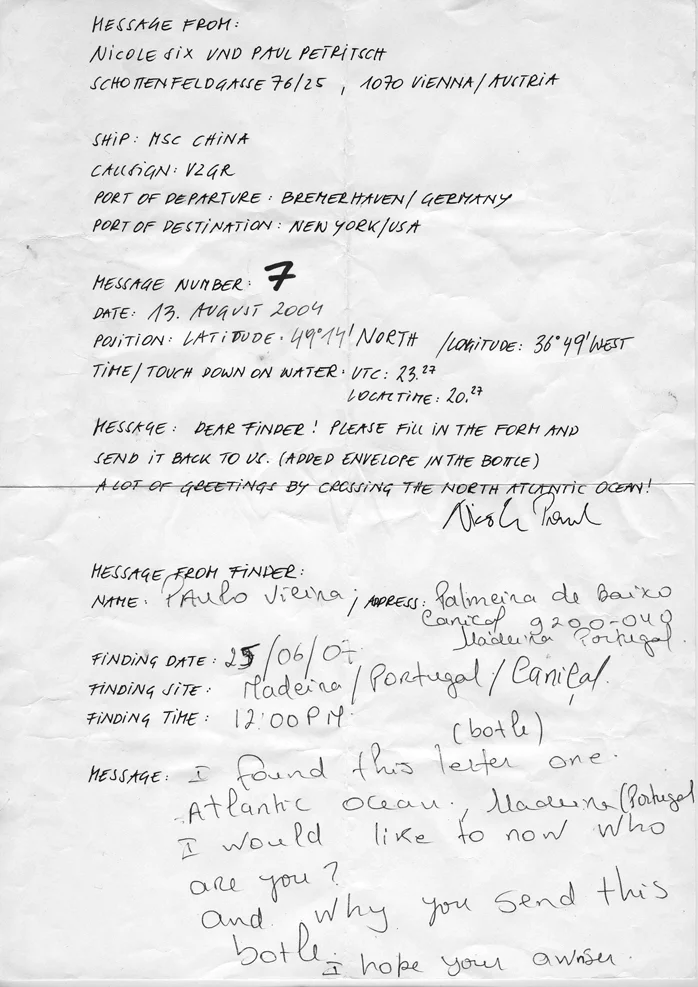

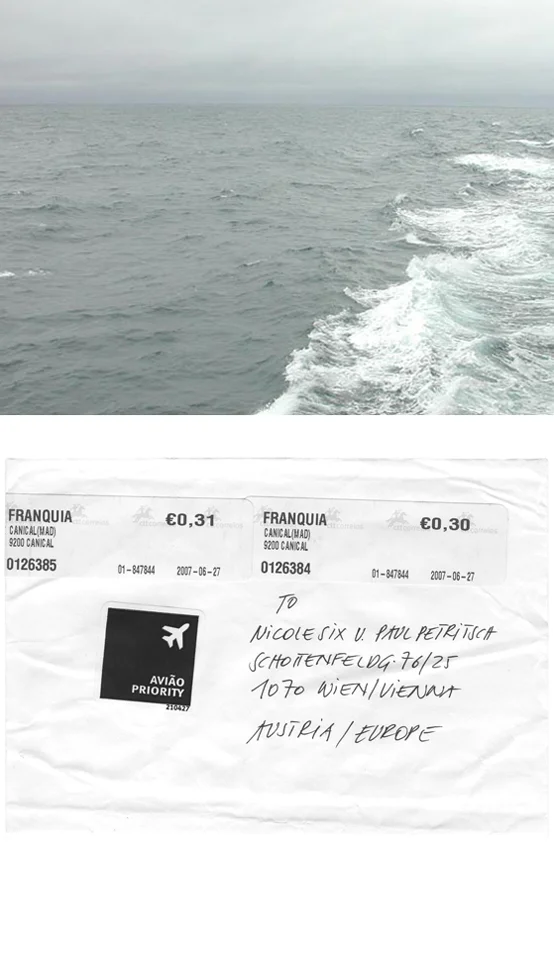

- Longitude / Latitude

Video on DVD

77 min, colour, silent

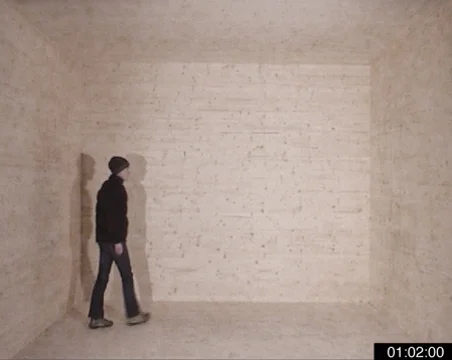

Raum

Video with sound on DVD

60 min, colour - 2003

- Camera dead

Video with sound on DVD

35 sec, colour

Räumliche Maßnahme (2)

Video with sound on DVD

two-channel projection

50 min, colour - 2002

- Räumliche Maßnahme (1)

Video with sound on DVD

28 min, colour

ARTISTS BOOKS (EDITIONS)

- 2025

- 2 Tonnen Kalkstein

Kunstraum IDEAL (Hg.)

Edition: 5

Archiv-Lesebuch (ChatGPT)

Kunstraum IDEAL (Hg.)

Edition: 5

Drugi Spomenik / Das andere Denkmal

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch mit Jakob Holzer (Hg.), Wien

unlimitiert - 2021

- Roxy, 27.05.2021 (Block Beuys)

Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt (Hg.),

Edition: 10+2 - 2020

- Unplugged

David Korecky, Galerie Rudolfinum (eds.), Prague

Edition: 99 - 2018

- Lost and Found

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 8+2 - 2016

- Fotoarchiv 30.06.2016-26.04.2015

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2 - 2015

- Fotoarchiv 26.04.2015-06.05.2014

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2 - 2014

- Das Meer der Stille

Landesgalerie Linz / Barbara Schröder (eds.), Linz

Fotoarchiv 14.04.2014-10.07.2012

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2 - 2012

- Aussicht kann durch Ladung verstellt sein

Kunstverein Medienturm (eds.), Graz

Edition: 20+2

Fotoarchiv 20.04.2012-09.03.2010

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2 - 2011

- Raum für 17 Minuten 6’23

Galerie im Taxispalais (eds.), Innsbruck - 2010

- Atlas

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch, Secession (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2

Fotoarchiv 20.02.2010-17.10.2009

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2

Innere Grenze

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 3+2 - 2009

- Fotoarchiv 28.09.2009-7.10.2008

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2 - 2008

- Fotoarchiv 05.10.2008-16.02.2007

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2 - 2007

- Fotoarchiv 21.01.2007-07.09.2005

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2 - 2005

- Fotoarchiv 16.08.2005-04.08.2004

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2 - 2004

- Fotoarchiv 06.06.2004-15.02.2001

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 20+2

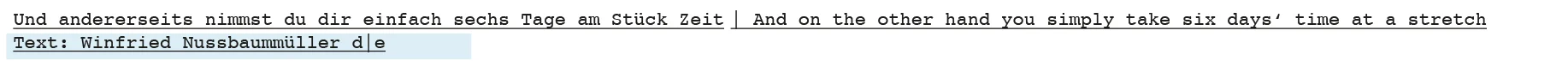

Raumbuch

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (eds.), Vienna

Edition: 3+2

FILME

- 2025

- Drugi spomenik / Das andere Denkmal

Video, 1 Kanal

32 min 22 sec

Ton, Farbe - 2024

- Seemeile (Sumbu und Pekel)

Video, 1 Kanal

20 min 49 sec

Ton, Farbe

Die Reise der Bilder

Video, 8 Kanal

24 min 24 sec - 33min 23 sec, Ton, Farbe - 2023

- Lueger Temporär

Video, 1 Kanal

22 min 11 sec, Ton, Farbe

05.01.2023 (Pečnikov travnik/Pečnik-Wiese)

Video, 4 Kanal

1h 50min, Ton, Farbe - 2021

- Pilot

(Dialogisch den Horizont expandieren

- von Klagenfurt nach Klagenfurt)

Video, 1 Kanal

11 min 08 sec, Ton, Farbe

Roxy, 27.05.2021 (Block Beuys)

Video, 1 Kanal

8 min 12 sec, Ton, Farbe - 2020

- Parallel Worlds

20.03.2020 / 01.04.2020 / 20.04.2020

Video, 3 Kanal

23 min 12sec, Ton, Farbe - 2017

- Ohne Titel (Albaner Hafen)

Video

3 Kanal Projektion

51 min, Farbe, Ton - 2015

- Das Denkmal

Video

2 Kanal Projektion

130 min, Farbe, Ton - 2014

- Raum für 5’16’’

Video

2 Kanal Projektion

5 min 16 sec, Farbe, Ton

Das Meer der Stille

Video

3 min 34 sec, Farbe, Ton - 2011

- Raum für 17 Minuten 6’23’’

Video

2 Kanal Projektion

6 min 23 sec, Farbe, Ton - 2009

- Das menschliche und das tierische Wesen

Video

5 Kanal Projektion

19 min, Farbe, Ton - 2007

- Ohne Titel, 12 Bauten von Peter Zumthor

Video

6 Kanal Projektion

480 min, Farbe, Ton

Nebel

Video auf DVD

30 min, Farbe, Ton - 2005

- Ohne Titel, Kunsthaus Bregenz

Video auf DVD

6 Kanal Projektion

72 h, Farbe, Ton

I’m too tired to tell you

Video auf DVD

17 min, Farbe, ohne Ton - 2004

- Longitude / Latitude

Video auf DVD

77 min, Farbe, ohne Ton

Raum

Video auf DVD

60 min, Farbe, Ton - 2003

- Camera dead

Video auf DVD

35 sec, Farbe, Ton

Räumliche Maßnahme (2)

Video auf DVD

2 Kanal Projektion

50 min, Farbe, Ton - 2002

- Räumliche Maßnahme (1)

Video auf DVD

28 min, Farbe, Ton

ARTISTS BOOKS (EDITIONS)

- 2025

- 2 Tonnen Kalkstein

Kunstraum IDEAL (Hg.)

Edition: 5

Archiv-Lesebuch (ChatGPT)

Kunstraum IDEAL (Hg.)

Edition: 5

Drugi Spomenik / Das andere Denkmal

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch mit Jakob Holzer (Hg.), Wien

unlimitiert - 2021

- Roxy, 27.05.2021 (Block Beuys)

Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt (Hg.),

Edition: 10+2 - 2020

- Unplugged

David Korecky, Galerie Rudolfinum (Hg.), Prag

Edition: 99 - 2018

- Lost and Found

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 8+2 - 2016

- Fotoarchiv 30.06.2016-26.04.2015

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2 - 2015

- Fotoarchiv 26.04.2015-06.05.2014

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2 - 2014

- Das Meer der Stille

Landesgalerie Linz / Barbara Schröder (Hg.), Linz

Fotoarchiv 14.04.2014-10.07.2012

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2 - 2012

- Aussicht kann durch Ladung verstellt sein

Kunstverein Medienturm (Hg.), Graz

Edition: 20+2

Fotoarchiv 20.04.2012-09.03.2010

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2 - 2011

- Raum für 17 Minuten 6’23

Galerie im Taxispalais (Hg.), Innsbruck - 2010

- Atlas

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch, Secession (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2

Fotoarchiv 20.02.2010-17.10.2009

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2

Innere Grenze

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 3+2 - 2009

- Fotoarchiv 28.09.2009-7.10.2008

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2 - 2008

- Fotoarchiv 05.10.2008-16.02.2007

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2 - 2007

- Fotoarchiv 21.01.2007-07.09.2005

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2 - 2005

- Fotoarchiv 16.08.2005-04.08.2004

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2 - 2004

- Fotoarchiv 06.06.2004-15.02.2001

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 20+2

Raumbuch

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch (Hg.), Wien

Edition: 3+2

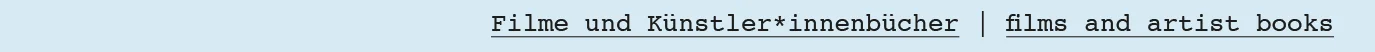

Nicole Six and Paul Petritsch have been realizing films, photographs, displays, artist books as well as site- and context-specific installations and projects in public space since 1997. They live in Vienna.

They explore the limits of our existence and our perception with expeditions into everyday life, through oceans, polar regions, concrete deserts as well as lunar landscapes. With their experimental test arrangements and interventions, they locate themselves and the viewer again and again in art spaces, architectures and landscapes.

BIOGRAPHY

Nicole Six

Born 1971 in Vöcklabruck, Austria

Academy of fine Arts Vienna, Sculpture

Paul Petritsch

Born 1968 in Friesach, Austria

University of Applied Arts Vienna, Architecture

1997 MAK Schindler Scholarship, Los Angeles

2004 International Studio & Curatorial Program / ISCP, New York

2005 Visiting Professor at Experimental Design, Kunstuniversität Linz

2006 State Fellowship for Fine Arts

2007 Kardinal König Art Award

2008 T-mobile Art Award

2008 Lectureship Modul Kunsttransfer, Institut für Kunst und Gestaltung, Vienna

2009 Austrian drawing Award

2011 - 2020 Member of the panel BIG Art – Kunst und Bau der BIG (Nicole Six)

2014 since 2014 Head of the Department Site-Specific Art, University of Applied Arts Vienna (Paul Petritsch)

2015 Member of the panel Kunsthalle Exnergasse (Paul Petritsch)

2017 Karl-Anton-Wolf-Award

2019 since 2019 board member of Camera Austria, Graz (Nicole Six)

2021 Guest professor of the Department Site-Specific Art, University of Applied Arts Vienna (Nicole Six)

2023 Lectureship at the department Kunst und Musik, Kunst und Kunsttheorie, University of Cologne (Nicole Six)

2023 Landeskulturpreis für Bildende Kunst, Upper Austria

2024 board member of Camera Austria, Graz (Nicole Six)

Landeskulturpreis für Bildende Kunst, Lower Austria

Collaboration since 1997

KONTAKT

Nicole Six and Paul Petritsch

Schottenfeldgasse 76/25

1070 Vienna/Austria

Tel. +43 1 95797 99

Fax +43 1 95797 99

Mail: office@six-petritsch.com

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch realisieren seit 1997 gemeinsam Filme, Fotografien, Displays, Künstlerbücher sowie orts- und kontextspezifische Installationen und Projekte im öffentlichen Raum. Sie leben in Wien.

Die Grenzen unseres Daseins und unserer Wahrnehmung erforschen sie mit Expeditionen in den Alltag, durch Ozeane, Polarregionen, Betonwüsten, wie auch Mondlandschaften. Mit ihren experimentellen Versuchsanordnungen und Eingriffen verorten sie sich und die Betrachter*innen immer wieder neu in Kunsträumen, Architekturen und auch Landschaften.

BIOGRAFIE

Nicole Six

1971 geboren in Vöcklabruck, Österreich

Studium der Bildhauerei an der Akademie der bildenden Künste

Paul Petritsch

1968 geboren in Friesach, Österreich

Studium der Architektur an der Universität für Angewandte Kunst

1997 Schindlerstipendium

2004 ISCP, New York

2005 Gastprofessur am Institut für Experimentelle Gestaltung, Kunstuni Linz

2006 Staatsstipendium für bildende Kunst

2007 Kardinal König Kunstpreis

2008 T-mobile Art Award

2008 Lehrauftrag Modul Kunsttransfer, Institut für Kunst und Gestaltung, TU Wien

2009 Österreichischer Grafikwettbewerb

2011 - 2020 Jurymitglied von BIG Art – Kunst und Bau der BIG (Nicole Six)

2014 seit 2014 Leitung Abteilung für ortsbezogene Kunst, Universität für Angewandte Kunst (Paul Petritsch)

2015 Künstlerischer Beirat der Kunsthalle Exnergasse (Paul Petritsch)

2017 Karl-Anton-Wolf-Preis

2019 seit 2019 Vorstandsmitglied der Camera Austria, Graz (Nicole Six)

2021 Gastprofessorin Abteilung für ortsbezogene Kunst, Universität für Angewandte Kunst (Nicole Six)

2023 Lehrauftrag am Department Kunst und Musik, Kunst und Kunsttheorie, Universität zu Köln (Nicole Six)

2023 Landeskulturpreis für Bildende Kunst, Oberösterreich

2024 Vorstandsmitglied der Camera Austria, Graz (Nicole Six)

Landeskulturpreis für Bildende Kunst, Niederösterreich

Zusammenarbeit seit 1997

KONTAKT

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch

Schottenfeldgasse 76/25

1070 Wien/Österreich

Tel. +43 1 95797 99

Fax +43 1 95797 99

Mail: office@six-petritsch.com

Sight, Shot and Free Fall

A true, barely perceptible intervention in a room only changes it minimally and temporarily. The action that has already taken place, which the traces on the wall are an indication of, makes itself present in the narration again: Paul Petritsch shot a hunting rifle twice in the Kunsthalle Exnergasse exhibition hall. The shots etch themselves into the beholder‘s imagination like two lines leading through the room. Is it possible to reconstruct the position of the no longer present shooter, to mark their coordinates with your own eyes? What direction would you have shot in?

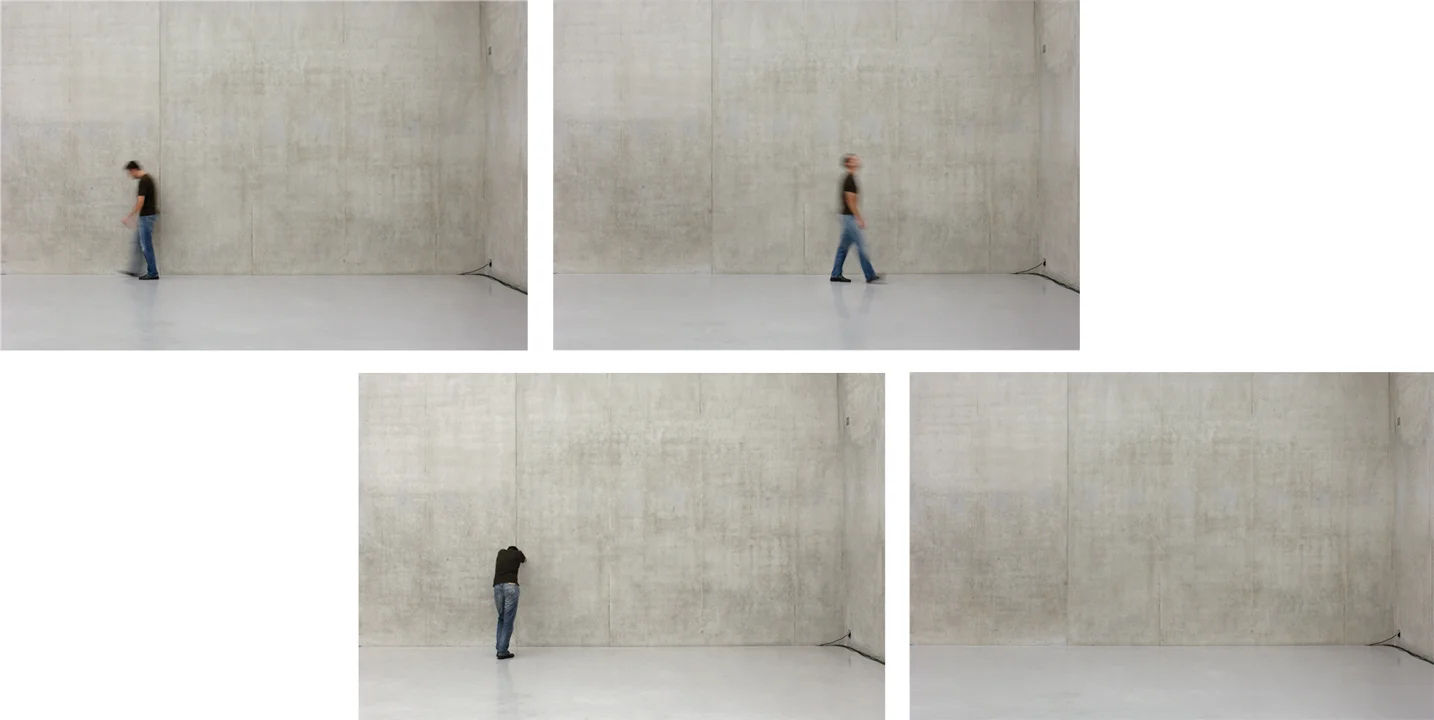

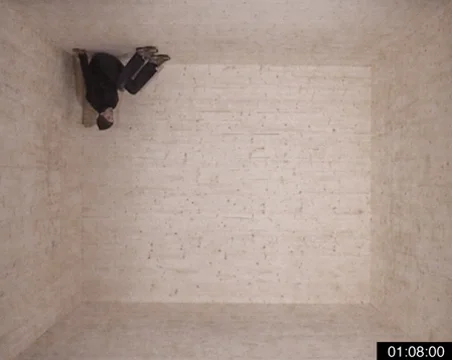

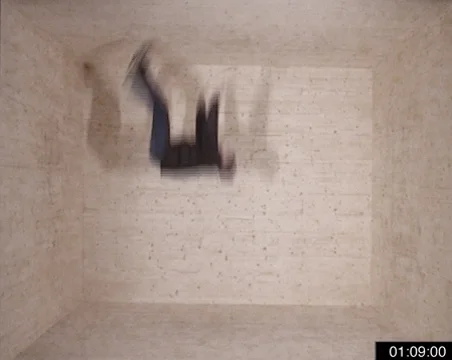

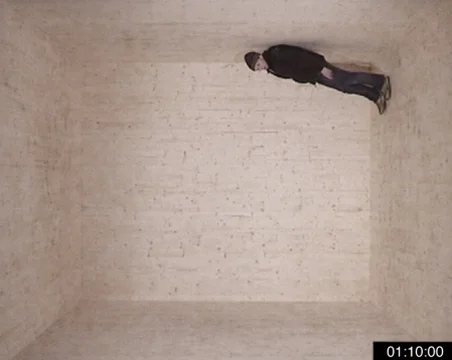

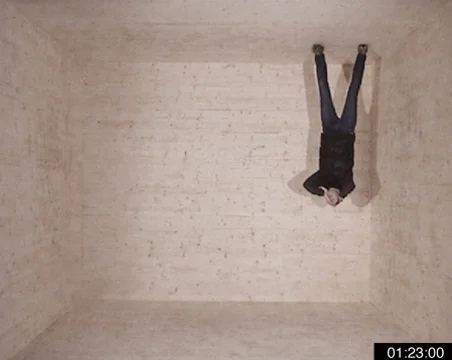

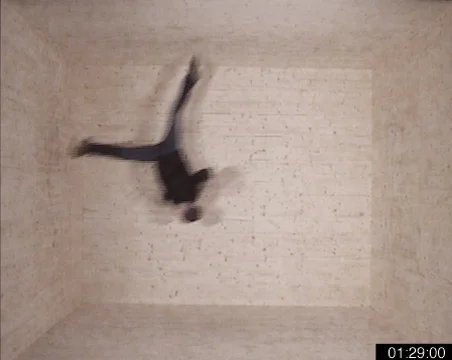

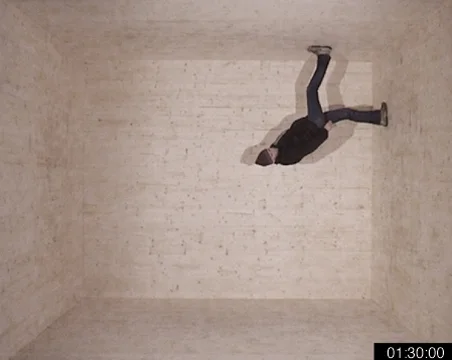

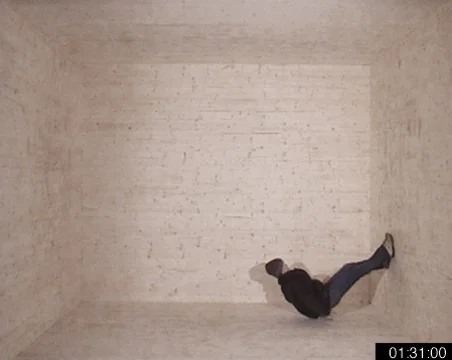

Nicole Six and Paul Petritsch address the confrontation between an individual and the material space surrounding him/her with artistic and bodily means in their performative interventions. Space is an actual condition for the possibility of action (“room for maneuver”), an immeasurable, vast counterpart that one has to come to terms with by adjustment, fitting in, appropriation, use, or through a direct intervention. Six and Petritsch create experimental situations in which their own physical and psychological bodies are used to make space comprehensible. At the same time, the documentation of these interventions using photography or a video camera explores the depiction of space and the events that have taken place in them.

The two artists revealed all the production conditions in the Kunsthalle Exnergasse without even creating something — instead they reduced the existing materiality. The disturbance of a seemingly intact unit made it possible to experience this relationship. Spatiality turns out to be a parallel, mathematically construed reality, an ideal sequence of parallel lines and right angles individuals use to orient their perceptions in which their actions help them fit in. But a small gesture is enough to resist this matter–of–fact subordination of the subject or work of art within the space. Two relatively random yet consciously shot diagonals in the space cut through the existing linear system. The still visible marks of the shots make it possible to trace the lines of these shots in our imagination and also represent two visual axes of the person who once stood in the room and aimed at the wall. This imaginary feedback in the mind of each new beholder updates the preceding beholder’s sighting.

A radical and absurd action also defines Camera Dead by Six/Petritsch. A video camera was thrown out of the 5th floor of a building and fell to the ground freely in 1.7 seconds. The only thing left is the last image the camera recorded before the impact ruined its functionality. This is another example of the extremely unusual and brutal handling of an artistic medium like shooting in an exhibition hall. Until now, Six/Petritsch had only used the camera for direct recording (without cutting, mounting or zooming). Before it was the human actor who was exposed to an unreasonable, disquieting, risky or dangerous situation in their earlier experimental sequences. Now it is the camera, the object itself that is experimented with. Hence the acting subject waives the possibility of steering the action: the fall and impact, the degree of destruction and the image recorded during the fall are all beyond its control. An imaginary line is traced once again — this time it is a fall that shows gravity as an extreme natural law recorded in this form by the used medium. And once again it is the absence of an irreversible action that has already taken place that fascinates us and defines the mystical aesthetics of the (very) last recording.

The fleeting moment of a shot or of an object’s fall can barely be captured by human perception. We have to use our imagination, as indeterminate and subjective as it may be, to perceive the remaining traces and create an image we can see. The violence of both of Six and Petritsch’s actions, one is against materiality and the other goes against a medium that records real spaces and creates imaginary spaces — can ultimately be seen as a rebellious expression of awareness regarding the possibilities and limitations of our own perception. Sight is recognized as a localizing instrument that can be used the way a shooting rifle or a recording camera is used, to chart an imaginary linear system in a room and thus define it. Measurement errors or limitations can be seen as indications of one’s own limits that help confirm one’s presence in this space.

Blick, Schuss und freier Fall

Der nichtige, kaum wahrnehmbare Eingriff in den Raum verändert diesen nur minimal und temporär. Die schon vergangene Handlung, auf welche die Spuren an der Wand verweisen, wird in ihrer Erzählung wieder präsent: zwei Mal hat Paul Petritsch mit einem Jagdgewehr in den Ausstellungsraum der Kunsthalle Exnergasse geschossen. Wie zwei Linien zeichnen sich die Schüsse in der Vorstellung des Betrachters durch den Raum. Ist es möglich, die Position des nicht mehr anwesenden Schützen zu rekonstruieren, ihre Koordinaten mit dem eigenen Blick nachzuziehen? Wohin hätte ich an seiner Stelle geschossen?

Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch treten in ihren performativen Rauminterventionen mit künstlerischen und körperlichen Mitteln die Konfrontation zwischen dem Individuum und dem es umgebenden, materiellen Raum an. Raum als eigentliche Bedingung der Möglichkeit für das Stattfinden einer Aktion („Handlungsspielraum“) wird als unermessliches, gewaltiges Gegenüber ausgewiesen, gegen das man sich durch Anpassung, Einordnung, Aneignung, Gebrauch oder durch einen direkten Eingriff zu behaupten hat. Six und Petritsch schaffen experimentelle Situationen, in welchen die eigene physische und psychische Körperlichkeit eingesetzt wird, um Räumlichkeit (be-)greifbar zu machen. Die Dokumentation durch Fotografie oder Videokamera betont dabei gleichzeitig die Frage nach der Abbildbarkeit von Räumen und den Ereignissen, die darin stattgefunden haben.

In der Kunsthalle Exnergasse hat das Künstlerduo alle Produktions-

bedingungen offen gelegt, ohne überhaupt etwas zu erzeugen – vielmehr wurde hier eine bereits existierende Materialität reduziert. Durch die Störung einer vermeintlich intakten Einheit wird diese erst in ihrer Verhältnismäßigkeit erfahrbar. Räumlichkeit entpuppt sich als eine parallele, mathematisch konstruierte Realität, eine ideale Anordnung aus parallel laufenden Linien und rechten Winkeln, an der das Individuum seine Wahrnehmung orientiert und in die es sich durch seine Handlungen einfügt. Eine kleine Geste reicht jedoch aus, um sich der selbstverständlichen Unterordnung des Subjekts oder des Kunstwerks im Raumzu widersetzen. Zwei relativ willkürlich und doch bewusst in den Raum geschossene Diagonalen schneiden gleichsam das existierende lineare System. Die noch vorhandenen Spuren der Schüsse ermöglichen es nicht nur, diese in Gedanken als Linien nachzuzeichnen, sie stehen auch für zwei Blickachsen eines Subjekts, das einst im Raum gestanden und auf die Wand gezielt hat. In der Rückkopplung an die Imagination jedes neuen Betrachters wird die bereits vergangene Einschreibung des Blicks eines Anderen wieder aktualisiert.

Eine radikale und absurde Handlung bestimmt auch die Arbeit Camera Dead von Six/Petritsch. Eine Videokamera wurde aus dem Fenster im 5. Stock eines Hauses geworfen und stürzte in 1,7 Sekunden in freiem Fall zu Boden. Übrig bleibt nur das letzte aufgezeichnete Bild, das entstanden ist, bevor die Kamera durch Zerstörung ihrer Funktionalität beraubt wurde. Wie beim Schuss in den Ausstellungsraum handelt es sich hier um einen äußerst unüblichen und brutalen Umgang mit einem künstlerischen Medium. Bisher hatten Six/Petritsch dieses allein zur direkten Aufzeichnung (ohne den Einsatz von Schnitt, Montage oder Zoom) benutzt. War es in ihren früheren experimentellen Anordnungen immer der menschliche Akteur gewesen, der vor der Kamera einer unangemessenen, verunsichernden, riskanten oder gefährlichen Situation ausgesetzt wurde, ist es nun die Kamera selbst, die Objekt des Versuchs wird. So verzichtet das handelnde Subjekt auch auf die Möglichkeit der Steuerung der Aktion: nach dem Abwurf liegen der Verlauf von Fall und Aufprall, das Ausmaß der Zerstörung sowie das erzeugte Bild außerhalb seiner Kontrolle. Wieder wird hier eine imaginäre Linie beschrieben – diesmal ist es die des Fallens, welche auf die Schwerkraft als externes Naturgesetz verweist und die in einer durch ein Medium vermittelten Form festgehaltenen wurde. Und erneut ist es die Absenz einer bereits geschehenen, nicht rückgängig zu machenden Handlung, welche uns fasziniert und die auch die mystische Ästhetik der (aller)letzten Aufzeichnung der Kamera ausmacht.

Der flüchtige Moment eines Schusses oder des Herunterfallens eines Gegenstandes ist durch die menschliche Wahrnehmung kaum zu erfassen. Aus den bleibenden Spuren muss unsere Vorstellung in all ihrer Unbestimmtheit und Subjektivität das eigentliche Ereignis erst zum Gesehenen ergänzen. Der gewaltsame Charakter der beiden Aktionen von Six und Petritsch – einmal gegen die Materialität des Raumes selbst und einmal gegen ein Medium gerichtet, das reale Räume abbildet und imaginäre Räume erzeugt – kann letztlich als rebellischer Ausdruck eines Bewusstseins der Möglichkeiten, aber auch der Begrenztheit der eigenen Wahrnehmung verstanden werden. Der Blick wird als ein Instrument der Verortung erkannt, das – ähnlich einem schießenden Gewehr oder einer aufzeichnenden Kamera – eingesetzt werden kann, um ein imaginäres, lineares System in den Raum zu schreiben und diesen so bestimmbar zu machen. Momente des Scheiterns oder der Einschränkung bei der Vermessung können dabei als Bemessung der eigenen Grenzen gerade zur Vergewisserung der Präsenz des Selbst im Raum beitragen.

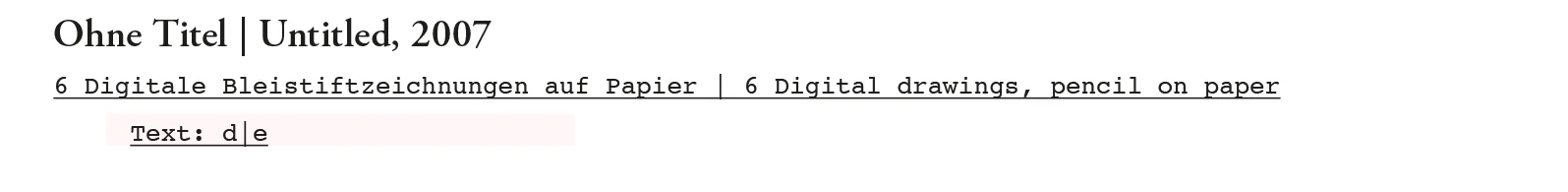

“Untitled” is a series of six drawings based on travelogues of the polar explorers and expedition leaders Julius Payer, Fridtjof Nansen, Salomon August Andrée (North Pole), and Ernest Henry Shackleton, Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott (South Pole). The drawings are

true to scale records of the respective individual itineraries.

„Ohne Titel“ ist eine sechsteilige Serie von Zeichnungen.

Grundlage der Zeichnungen sind Reiseberichte der Polfahrer

Julius Payer, Fridtjof Nansen, Salomon August Andrée (Nordpol)

und Ernest Henry Shackleton, Roald Amundsen und Robert

Falcon Scott (Südpol). Die Zeichnungen halten die individuelle

Reiseroute maßstabsgleich fest.

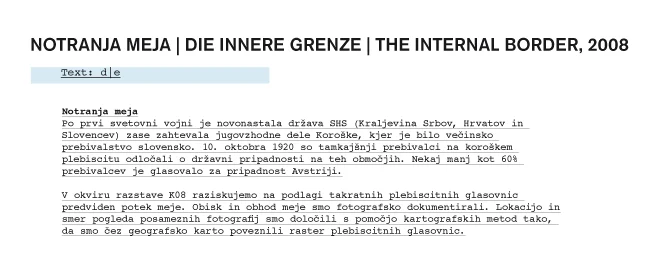

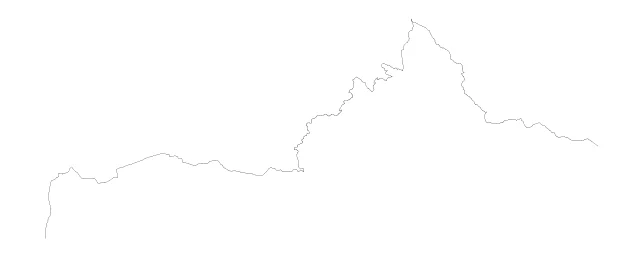

After World War One an area in Carinthia’s south east, where the majority of the population spoke Slovene, was claimed by the SHS state (the “Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes”). On October 10, 1920 a plebiscite decided upon the national future of these parts: just under 60% of the population living there voted against secession and for union with Austria.

On the occasion of the K08 exhibition we the course of the border as it was then planned examine on the basis of the map of the plebiscite. Visiting and walking the length of that frontier line is being documented photographically. By analogy to cartographic methods we put a certain screen across the map, thus defining place, viewpoint and line of sight of the photos.

The internal Border, 2008 was produced in conjunction with the exhibition “K08: Emancipation and Confrontation — Art from Carinthia from 1945 to the Present”.

Group Show

Curator: Silvie Aigner

Nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg waren die mehrheitlich von Slowenen bewohnten Gebiete im Südosten Kärntens durch den SHS-Staat (Königreich der Serben, Kroaten und Slowenen) beansprucht worden.

Am 10. Oktober 1920 wurde per Volksabstimmung über die staatliche Zugehörigkeit dieser Gebiete entschieden: Knapp 60% der dort lebenden Bevölkerung stimmte für einen Verbleib bei Österreich.

Anlässlich der Ausstellung K08 untersuchen wir anhand der Abstimmungskarte den damals erwogenen Grenzverlauf. Das Aufsuchen und Begehen der Grenze wird von uns fotografisch dokumentiert.

Ort und Blickrichtung der jeweiligen Fotoaufnahmen wurden – in Anlehnung an kartografische Methoden – allein durch ein bestimmtes Raster, das wir über die Karte legten, definiert.

Die Innere Grenze, 2008 wurde anlässlich der Ausstellung „K08: Emanzipation und Konfrontation – Kunst aus Kärnten von 1945 bis heute“ produziert.

Gruppenausstellung

Kuratorin: Silvie Aigner

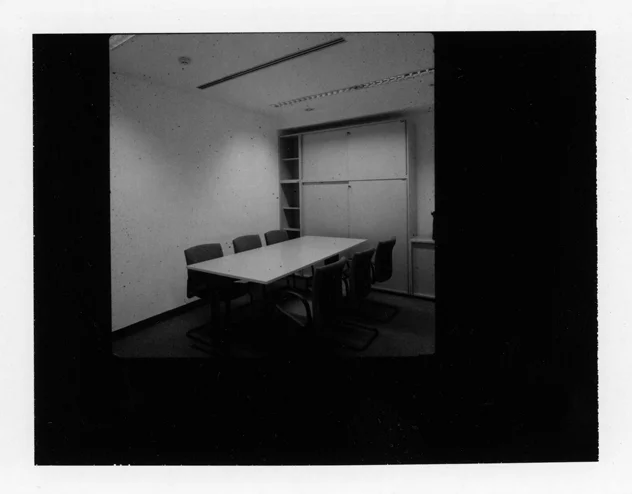

Starting point:

The competition advertised for redesigning the film studios at the campus of the University of Music and Pictorial Arts called for questioning and redefining the studios’ location within the campus and its position in the city.

Project:

The exteriors of the film studio (Uni Campus) is temporarily filled with people, like in movies’ crowd scenes. For such an operation the actual presence of people is needed (i. e. the corresponding translation): The idea is to have 5,000 people come to the campus during a set time of two hours. The realization of this idea corresponds with organising a film production. Yet, this set ends with the moment of “Film ab!” (Camera is rolling). (It is of importance to the concept that the set is exclusively experienced here and now. The potential “Camera is rolling”—“Film ab!”— is not carried out).

There exists no documentation of this project. No documentary evidence remains, be it a construction, a film or photographs. The project materializes through personal account and imagination.

Bestand:

Der Wettbewerb zur Gestaltung der Filmstudios an der Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst gibt Anlass das Studiogebäude innerhalb des Campus zu thematisieren, und seine Lage in der Stadt neu zu definieren.

Projekt:

Der Außenraum (Uni Campus) wird mit einer Vielzahl von Personen, gleich einer filmischen Massenszene, temporär gefüllt. Diese Intervention bedarf der tatsächlichen Präsenz von Menschen (analoge Umsetzung der Situation): Idee ist, dass sich in einem Zeitraum von ca. 2 Stunden etwa 5.000 Personen auf dem Campus aufhalten. Die Umsetzung des Projekts entspricht der Organisation einer Filmproduktion. Dieses Set ist bis zum Moment „Film ab“ konzipiert. (Von konzeptueller Bedeutung ist, dass das Set ausschließlich in der Gegenwart des Moments wahrgenommen wird. Der – theoretisch mögliche – Moment „Film ab!“ wird nicht in die Praxis umgesetzt.)

Das Projekt wird nicht dokumentiert. Es bleiben keine baulichen, filmischen oder fotografischen Dokumente. Das Projekt manifestiert sich durch Erzählung und Imagination.

Statics and Extras

Extras is the name commonly given to those people who augment a scene without themselves actively appearing. Those who contribute to the liveliness and realism of a picture without stealing the show from the leading actors. Extras are indispensable for framing action as a kind of moving background to the extent that they lend solidity and cohesion, in fact a kind of statics. For the foreground action they should not be more than living wallpaper but for the unity of a picture they represent almost something like a supporting foundation. Thus the placing of extras in a scene does in fact seem to have something to do with applied statics.

The name “extras” is significant. Those special additions which contribute to improving fittings and comfort. but also to optimising the basic functioning of an act, a scene or a setting through the specific added value that they bring with them. Extras could also be seen as special picture surplus — those supporting components which are not in themselves necessarily seen but without which a noticeable emptiness and fragility would prevail.

Only when one specifically addresses the role of extras does one get on the track of the functional connection of a picture, the interplay of figures and background, of plot and its location and of dynamics and immobility. Only focus on the many inconspicuous extras enables the opening up of the fine motor activity of a pictorial ensemble.

Film ab!<font color="#FFFFFF">.</font> by Nicole Six and Paul Petritsch starts out from exactly such apparently minor matters. Minor matters and digressions which shift to the centre of events and effectively undermine the common connection of meaning between an architectonic setting and its primary action components, from its artistic environment to the actors to be encountered there each day. The shift which Six and Petritsch make with their Kunst–am–Bau<font color="#FFFFFF">.</font> (Art on the Construction Site) project on the campus of the University of Music and the Performing Arts, Vienna, includes several levels: location-specific<font color="#FFFFFF">.</font> — related to the production site of the film studio, pictorially grammatical — with the targeted generation of a mass scene, and not least artistic–architectonic<font color="#FFFFFF">.</font> — instead of a permanent design intervention an ephemeral event takes place. On all these levels they divert attention towards special surpluses, to extras in the sense described above, who would not straightaway be expected in a Kunst–am–Bau<font color="#FFFFFF">.</font> connection, but who instead show all the more clearly where its most neuralgic and sometimes trouble-prone places are.

There is firstly the location itself, the cubical new construction of the

film studio building on the campus of the University of Music and the Performing Arts. How tempting it must have been to fill the plain, mostly window-less outside walls with all kinds of reference materials from film and media contexts. With reminiscences of cinema history, samples of subjects negotiated at this spot or perhaps even as an advertising space for the student works produced inside. None of all this. As qualified architects Six and Petritsch do not intervene in the grid–like design and geometrical balance of the facade. Instead they see the surrounding space of the building, a newly acquired place, as their primary play area — a forum of a special kind which calculatingly only permits itself to be used by a certain number of people.

Film does not necessarily mean a star cast, but sometimes also anony- mous mass production, and where, apart from this central outdoors space decorated with the new construction, can such a thing be realised? By taking up a method of film staging, Six and Petritsch do not only show the functional context of the building but shift it in the direction of a special form of staging, mostly reserved for very expensive (or very cheap) productions. Film and masses, the latter usually only experienced at the reception end of the medium of film, are brought together in one of their original overlapping moments.

As already suggested, a basic shift is at work in this combination. In the context of film the masses, or the extras embodying them, usually function as the background to a storyline — as an anonymous, undifferen-tiated foil, from which the protagonists stand out in their individuality. In contrast there is a line of film history, coming from early cinema via Benjamin and Krakauer to the Soviet revolutionary film in which the masses can themselves become an actor. Not as part of the setting or social basis of a scene but as a collective subject, which sees itself as an entity of the plot — as impressively demonstrated in Eisenstein‘s Battleship Potemkin and October.<font color="#FFFFFF">.</font> To stage a mass as a mass and not as the background for a special scene enters this cinema historical tradition — incidentally a tradition which appears to be more and more forgotten with the prevalence of the Hollywood film. Or if not already completely supplanted, then threatened to be confined to certain genres such as historical and costume films.

With Film ab!<font color="#FFFFFF">.</font> Six and Petritsch recall this moment of the collective subject without individual protagonists or storyline specifications. However, in contrast to Eisenstein and Co., they leave the political purpose of this subject completely open. They do so by as it were hollowing out the foundations of the form of staging of mass scenes. It does not only remain completely unspecified for what<font color="#FFFFFF">.</font> reason 5,000 extras should gather on a May afternoon in 2007 — except in fact to generate a mass scene, but also any kind of instructions are omitted, both for those present at the location as well as with regard to possible documentation of the event. The framework of action is confined, so to speak, to the pure formality of the transaction of a contract — for example, one of the “main acts” of the project is that each individual is paid his/her promised fee as an extra. Following this, also regulated by contract, the campus is cleaned to remove all traces of the event in no time at all. An audio–visual documentary is not planned by the artists but is also not expressly prohibited.

Two things are brought to expression by this opening up or infiltration of the staged mass event. In the first instance a bridge is built between the above–mentioned tradition of cinematic “mass subjectivisation” and the spontaneous action with a situationist touch. Spontaneous may not be the right word here because the event was minutely planned for months but the staging of a mass gathering, simply for the sake of gathering, certainly has features of the line of tradition which stretches from aimless wandering about the streets to sit-ins at short notice and so–called “flash mobs”. Nowadays every more sustainable or longer term perspective on such forms of action may have evaporated but Six and Petritsch put exactly this lack of a common agenda or a collective project up for discussion by exposing the temporary formation of a swarm of people and its subsequent dissolution as almost a formal act void of any form

of content. In Film ab!<font color="#FFFFFF">.</font> the mass is stripped of any power; at the most it

still bears superficial features of deflated power fantasies. But even this phantasm quickly dissolves to nothing, the more so as the action men- tioned in the title, the actual shooting of the film, does not take place.

With this gesture, which totally concentrates on transience and the nature of the process, the Kunst–am–Bau<font color="#FFFFFF">.</font> idea not least experiences a decisive shift. A main criterion of this idea still seems to lie in how a built structure can be used for visual, sculptural or other creative interventions. The concept behind it sees architecture primarily as a kind of screen to which art can be applied with a brush or a projector. The problems which this poses, especially when buildings change their function or the layers applied to them begin to crumble, are well known and need not be repeated here.

Six and Petritsch do not avoid this basic idea but radicalise it. It is not that the newly constructed building is a screen but the whole environment of the building in which the new structure only occupies one place (even if is central). Instead of being a projection surface, it give the conceptual impulse for the action Film ab!<font color="#FFFFFF">.</font> and functions — not permanently but only for the duration of one afternoon — just as much as a part of the staging as the whole surrounding area.

Film ab!<font color="#FFFFFF">.</font> makes the Kunst–am–Bau<font color="#FFFFFF">.</font> concept dynamic in that nothing adheres to the building except the potential memory of it having been the setting of a mass scene: not as a once–and–for–all stipulation but as an exemplary stimulus to manifold imaginary uses. These may be transient and variable but because of this they are in no way less explosive. Instead of putting a permanent stamp on architecture, they point towards its ideal expandability and what are today perhaps unforeseeable ways of using it.

The 5,000 extras thereby take on a catalytic function. In that a mass of extras — one time, randomly and temporarily — fills a campus for one afternoon and then leaves again — this variable occupancy is shown. In this way the extras make a kind of background story appear which — open to a variety of uses — lends the built scenario an additional dimension. It is as if the statics of the place depend above all on this variability and flexibility, as the many extras brilliantly demonstrate.

Statik und Statisten

Statisten nennt man gemeinhin jene Personen, die eine Szene anreichern, ohne selbst aktiv in Erscheinung zu treten. Die zur Lebendigkeit und Realitätsnähe eines Bildes beitragen, ohne den Hauptfiguren die Show zu stehlen. Statisten sind für die Rahmung eines Geschehens in dem Maße unerlässlich wie sie, als eine Art bewegter Hintergrund, einem Szenario Festigkeit und Zusammenhalt, ja eine gewisse Statik verleihen. Für die vordergründige Handlung mögen sie nicht viel mehr als eine lebende Tapete abgeben, doch für die Einheit eines Bildes stellen sie fast so etwas wie die tragende Grundierung dar. Die Platzierung von Statisten in einer Szene scheint demnach tatsächlich etwas mit angewandter Statik zu tun zu haben.

Bezeichnend ist, dass man Statisten im Englischen „Extras“ nennt. Jene speziellen Zusätze also, die dazu beitragen, Ausstattung und Komfort zu verbessern, aber auch das grundlegende Funktionieren eines Akts, einer Szene, einer Einstellung durch den eigentümlichen Mehrwert, den sie mit sich führen, zu optimieren. „Extras“ könnten auch als spezieller Bild-Überschuss gesehen werden – jene tragenden Bestandteile, die man selbst nicht notwendig wahrnimmt, ohne die aber eine merkwürdige Leere und Brüchigkeit vorherrschen würde. Erst wenn man sich dezidiert der Rolle von Statisten zuwendet, kommt man dem Funktions- zusammenhang eines Bildes, dem Wechselspiel von Figuren und Hintergrund, von Handlung und deren Verortung, von Dynamik und Unbewegtheit auf die Spur. Erst der Fokus auf die vielen unscheinbaren „Extras“ lässt die Feinmotorik eines bildlichen Ensembles erschließen.

Film ab!<font color="#FFFFFF">.</font> von Nicole Six und Paul Petritsch setzt genau bei solchen scheinbaren Nebensächlichkeiten an.

Nebensächlichkeiten und Abschweifungen, die in den Mittelpunkt des Geschehens rücken und den gängigen Bedeutungskonnex zwischen einem architektonischen Setting und dessen primären Handlungskomponenten, von seiner Kunst- ausstattung hin bis zu den dort täglich anzutreffenden Akteuren, nachhaltig unterlaufen. Die Verschiebung, die Six und Petritsch mit ihrem Kunst-am-Bau-Projekt am Campus der Universität für Musik und Darstellende Kunst vollziehen, umfasst mehrere Ebenen: ortspezifisch – auf den Produktionsort der Filmstudios bezogen – bildgrammatisch – mit der gezielten Generierung einer Massenszene – und nicht zuletzt künstlerisch-architektonisch – anstelle einer bleibenden gestalterischen Intervention findet ein ephemeres Ereignis statt. Auf all diesen Ebenen lenken sie die Aufmerksamkeit hin auf spezielle Überschüsse, auf „Extras“ im oben beschriebenen Sinn, die man auf Anhieb nicht in einem Kunst-am-Bau-Zusammenhang erwarten würde, die dafür aber umso deutlicher vor Augen führen, worin dessen neuralgische und mitunter störungsanfälligsten Stellen liegen.

Da ist zunächst der Ort selbst, der kubische Neubau des Filmstudio- gebäudes auf dem Campus der Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst. Wie verlockend muss es doch gewesen sein, die planen, großteils fensterlosen Außenwände mit allerlei Referenzmaterialien aus Film- und Medien zusammenhängen zu bespielen. Mit Reminiszenzen an die Kinogeschichte, Samples der an diesem Ort verhandelten Sujets, oder vielleicht sogar als Werbefläche für die darin produzierten Studenten-Arbeiten. Nichts von alledem. Als gelernte Architekten greifen Six und Petritsch nicht in die rasterartig gestaltete und geometrisch ausgewogene Fassade ein. Stattdessen begreifen sie den Umraum des Gebäudes, einen neu gewonnenen Platz, als ihre primäre Spielfläche – ein Forum der besonderen Art, das sich kalkuliertermaßen von einer bestimmten Anzahl von Personen nutzen lässt.

Film heißt nicht unbedingt Star-Ensemble, sondern mitunter auch anonyme Massenproduktion, und wo sonst als in diesem zentral mit dem Neubau bestückten Außenraum ließe sich ein solche umsetzen? Indem Six und Petritsch zu einem Mittel der filmischen Inszenierung greifen, führen sie nicht nur den Funktionskontext des Gebäudes vor Augen, sondern verschieben diesen in Richtung einer speziellen, meist ganz teuren (oder ganz billigen) Produktionen vorbehaltenen Inszenierungsform. Film und Masse, letztere meist nur am Rezeptionsende des Kinomediums wahrgenommen, werden so in einem ihrer ursprünglichen Überschneidungsmomente zusammengeführt.

In dieser Zusammenführung ist, wie bereits angedeutet, eine grund- legende Verschiebung am Werk. Üblicherweise fungieren die Masse bzw. die sie verkörpernden Statisten im filmischen Zusammenhang als Hintergrund einer Handlung – als anonyme, undifferenzierte Folie, von der sich die ProtagonistInnen in ihrer Individualität abheben. Dagegen existiert eine filmhistorische Linie, aus dem frühen Kino kommend, über Benjamin und Krakauer bis hin zum sowjetischen Revolutionsfilm, der zufolge die Masse selbst zum Akteur werden kann. Nicht als milieuhafte oder soziale Grundierung einer Szene, sondern als kollektives Subjekt, das sich selbst als Handlungsinstanz begreift – so wie dies Eisensteins Panzerkreuzer Potemkin oder Oktober<font color="#FFFFFF">.</font> eindrucksvoll vorführen. Eine Masse als Masse zu inszenieren, und nicht als Hintergrund eines speziellen Aktes, schreibt sich in diese filmgeschichtliche Tradition ein – eine Tradition im übrigen, die mit dem Überhandnehmen des Hollywoodkinos immer mehr in Vergessenheit zu geraten scheint. Oder wenn schon nicht ganz verdrängt, so doch auf bestimmte Genres wie den Historien- und Kostümfilm beschränkt zu werden droht.

Six und Petritsch rufen mit Film ab!<font color="#FFFFFF">.</font> dieses Moment des kollektiven Subjekts, ohne individuelle ProtagonistInnen bzw. Handlungsvorgaben, in Erinnerung. Allerdings lassen sie, anders als Eisenstein und Co., die politische Bestimmung dieses Subjekts gänzlich offen. Sie tun dies, indem sie die Inszenierungsform der Massenszene gleichsam in ihren Grund- festen aushöhlen. Denn nicht nur bleibt völlig unbestimmt, wozu<font color="#FFFFFF">.</font> sich die 5.000 Statisten an dem Mai-Nachmittag 2007 versammeln sollen – außer um eben eine Massenszene zu generieren. Vielmehr wird auch jegliche Handlungsanweisung, sowohl an die sich vor Ort Einfindenden wie auch im Hinblick auf eine eventuelle Dokumentation des Geschehens, ausgespart. Der Handlungsrahmen beschränkt sich, wenn man so will, auf die pure Formalität der Abwicklung eines Auftrages – so wird beispielsweise, als eine der „Hauptaktionen“ des Projekts, jedem/r Einzelnen das ihm/ihr vertraglich zugesicherte Statisten-Honorar ausbezahlt. Im Anschluss daran wird, ebenfalls per Vertrag geregelt, der Campus gereinigt, um jegliche Spuren des Ereignisses im Handumdrehen zu beseitigen. Eine audiovisuelle Dokumentation ist von den KünstlerInnen nicht vorgesehen, wird aber auch nicht ausdrücklich untersagt.

In dieser Öffnung bzw. Unterwanderung des insze-nierten Massen-Events kommt zweierlei zum Ausdruck. Zunächst erfolgt damit ein Brückenschlag zwischen der erwähnten Tradition filmischer „Massen-Subjektivierung“ hin zur situationistisch angehauchten Spontan-Aktion. Spontan mag hier nicht das richtige Wort sein, da das Ereignis ja minutiös und monatelang geplant ist, aber die Inszenierung einer Massenzusammenkunft, rein um der Zusammenkunft willen, trägt durchaus Züge jener Traditionslinie, die vom ziellosen Umherschweifen in den Straßen bis hin zu kurzfristigen Sit-ins, Platzbesetzungen und so genannten „Flash Mobs“ reicht. Heute mag jede tragfähigere bzw. längerfristige Perspektive solcher Aktionsformen verflogen sein, aber Six und Petritsch stellen genau dieses Fehlen einer gemeinsamen Agenda, eines kollektiven Projekts, zur Diskussion, indem sie die vorübergehende Bildung eines Menschenschwarms und dessen anschließende Auflösung gleichsam als formellen, jeglicher Inhaltlichkeit entleerten Akt exponieren. Die Masse ist in Film ab!<font color="#FFFFFF">.</font> jeder Macht entkleidet; allenfalls trägt sie noch oberflächliche Züge entleerter Machtfantasien. Aber selbst dieses Fantasma löst sich schnell in nichts auf, zumal die im Titel angesprochene Aktion, der tatsächliche Filmdreh, ausbleibt.